This is the second of four articles about the cluster of favelas in Curicica, Jacarepaguá that are awaiting urban integration projects through the Morar Carioca upgrading program.

A community that breathes.

Carlos Alberto “Bezerra” Costa, Resident’s Association president of Asa Branca, stopped to look over the row of houses that greeted us into favela Abadiana, his voice a few keys graver than usual as he spoke: “To tell you the truth… in a year or two, this road probably won’t be here.”

It’s often difficult to gauge the human energy of a place on an early Tuesday afternoon, but the traces of life that were visible that day made it clear this was a community that breathed. An older woman walked with her grandson’s hand in hers, exchanging quick smiles and quick comments with her neighbor as she passed. A pair of friends leaning on a stack of tires by the avenue entrance greeted Bezerra with a joke and some pats on the back. Laundry hung on lines over the river below, the bright colors of a family’s garments soaking in the heat of the sun.

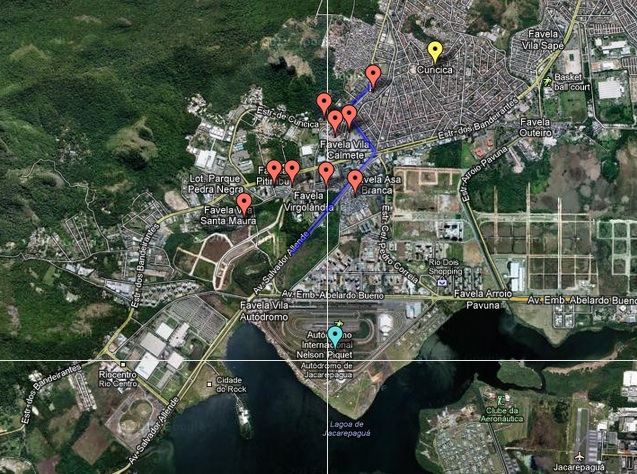

All of this – by what little certainty current information allows – is set to be removed from land that is slated to be part of the city’s TransOlímpica highway, a project that will connect the Olympic Stadium in Barra da Tijuca to another Olympic cluster in the north. A promotional video shows the projected path of the highway as a green line that glides easily across the landscape of Rio, erasing whole sections of inhabited land that include residences in and around Curicica.

“We just want to know.”

In some communities, the damage will be minimal. The part of Asa Branca that conflicts with the TransOlímpica is mostly new construction by residents whom Bezerra had personally warned, prior to building, of the impending risk of relocation. And according to José “Tilzé” da Cruz, president of Vila Calmete, the only part of his community that the bus line will cut through is the first row of houses at the community’s entrance. For Bezerra and Tilzé, then, the primary concern is to house the displaced within their communities: a challenging but manageable goal with a smaller number of relocations.

This is not the case in Vila União da Curicica, a great part of which sits at the edges of Estrada da Curicica and Estrada Calmete, streets that are set to be widened three times their current width in order to accommodate six lanes of traffic. As the other side of Estrada da Curicica contains a municipal hospital, it looks painfully predictable that the expansion will happen in the direction of the community, swallowing rows of houses to make way for the bus line.

“The way it looks, they’re going to come and remove people from the community,” said Vânia de Jesus Júlio Neri, current president of the Residents’ Association of Vila União. “But we don’t know where we’ll be going. We don’t know if it will be on Estrada da Curicica or a completely different part of Rio. We don’t know anything.”

It hasn’t been for lack of trying. Over the past year, Vânia has been busy contacting government officials, requesting for mayor Eduardo Paes or a representative to send concrete details to Vila União’s residents on the subject of upcoming evictions and relocations. But so far, all attempts at dialogue have fallen on deaf ears. “What we want,” said Vânia, “is for the Prefeitura (city government) to come, sit down, and just talk to us about what might happen to our community. We just want to know. But that hasn’t happened.”

It hasn’t been for lack of trying. Over the past year, Vânia has been busy contacting government officials, requesting for mayor Eduardo Paes or a representative to send concrete details to Vila União’s residents on the subject of upcoming evictions and relocations. But so far, all attempts at dialogue have fallen on deaf ears. “What we want,” said Vânia, “is for the Prefeitura (city government) to come, sit down, and just talk to us about what might happen to our community. We just want to know. But that hasn’t happened.”

Second to the obvious fear of eviction, it’s this lingering ambiguity that’s perhaps most paralyzing. Without official word of the city government’s plans, Vila União is caught in a space that offers no real avenues for mobilization, defense, or anything other than just waiting.

Paired with the upcoming Morar Carioca projects in the community, Vânia and fellow residents find themselves thrown around in a sea of mixed messages. “Some people say we have to leave, and others say that Morar Carioca is going to come and improve Vila União. So I just don’t really understand.”

A sudden fracture.

“A community is more than just the space it inhabits,” said Regina Sônia Gomes Baptista, known by Sônia, former president of Vila União. “It’s the relationships people have formed, tied together by that shared environment. And the security and happiness that all of this brings. So no one wants to leave.”

“A community is more than just the space it inhabits,” said Regina Sônia Gomes Baptista, known by Sônia, former president of Vila União. “It’s the relationships people have formed, tied together by that shared environment. And the security and happiness that all of this brings. So no one wants to leave.”

It’s this simple truth that has gone ignored over the history of removals and relocations orchestrated by the city government. Though the (often forced) “option” of relocation may guarantee housing to the dispossessed, the baseline accomodations come devoid of the human necessities of culture and community with which many favelas are replete. A fraction of the community evicted leaves the remaining population with broken connections and dislocated relationships. Decades of living, building, and knowing a place and its people are suddenly fractured. “All we ask is that they have a bit of caution with us,” said Vânia.

“At the very least,” she continued, “we want to stay in Jacarepaguá.” In addition to maintaining proximity with their friends and family, the residents of Vila União also want to stay close to and be able to keep their jobs. Previous removals in other communities have placed people in the distant west neighborhoods of Santa Cruz and Cosmos, far from Jacarepaguá and further still from Centro and Zona Sul where some residents already make daily commutes. As for finding new employment in those distant neighborhoods – labeled “regiões dormitórios” for the lack of opportunities within them – well, chances are slim.

Sônia also voiced concerns about the living conditions that those evicted from Vila União would find themselves in. “A room, a kitchen, a bathroom – a kitchenette, basically,” she said, is a far cry from the spacious and elaborate dwellings that have come to define much of her community. In many public housing projects, she explained, “the walls are thin and the rooms are cramped. Not even animals like to live that close.”

“Our only fear.”

“By removing people from their houses, by breaking the sense of security the residents have between each other, the Prefeitura will create a violent place where there wasn’t one,” said photographer and activist Maurício Hora last month during an interview about evictions in Providência, Rio’s original favela community. On the other side of the city, Sônia had similar concerns about the prospect of a displaced Vila União. “When you watch the news,” she asked, “where do you find the highest indices of violence? In places where people live in cramped conditions with little dignity.”

The houses that line the streets of Vila União have yet to be marked for removal. But in a city where the unsuspecting residents of Providência came home to find eviction tags sprayed on their outer walls – where Verdejar, a well-established and respected environmental NGO, was notified, dispelled, and forced to watch their headquarters torn down in the space of a few hours – silence from the municipality is an intolerable weight that proves difficult to shake off for the residents of Vila União and Abadiana.

As we sat outside Sônia’s house, enjoying coffee and biscuits amid the chirping of her pet birds, the comings and goings of her constant visitors, and the trees in her backyard, there was little in the immediate moment to be discontent about. But uncertainty has darkened the horizon. “We’ve built a good life for ourselves here,” said Sônia. “Our only fear is that some crazy government will come in and mess with everything.”

The website for Rio’s TransOlímpica project is filled with bright sentiments, content smiles, and promises of “social inclusion.” But the legacy that these Olympic projects have already left in these early stages rings more like the opposite: fear, frustration, and displacement for people at the margins of those decisions.

This is the second of 4 articles about the cluster of favelas in Curicica, Jacarepaguá, Rio de Janeiro prior to upgrading through the City’s Morar Carioca program. The next article will show the feelings of promise and doubt that await the upcoming urban integration project.

Click here to see more photos of the communities featured in this series, or watch the slideshow below: