Mães de Cria and the Coronavirus Pandemic

On May 5, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the end of the Covid-19 global emergency. Over three years later, the impacts of the pandemic can still be seen on the education of children and adolescents. In the city of Rio de Janeiro, a study by researchers from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and Durham University, UK, found that children from poorer backgrounds learned only half as much as recommended through remote teaching during the pandemic period.

In 2020, favela newspaper Fala Roça reported that, according to the Municipal Health Secretariat (SMS), at one point, Rocinha had the highest number of Covid-19 cases in Rio’s favelas. This alongside other impacts of the pandemic on residents, such as high unemployment.

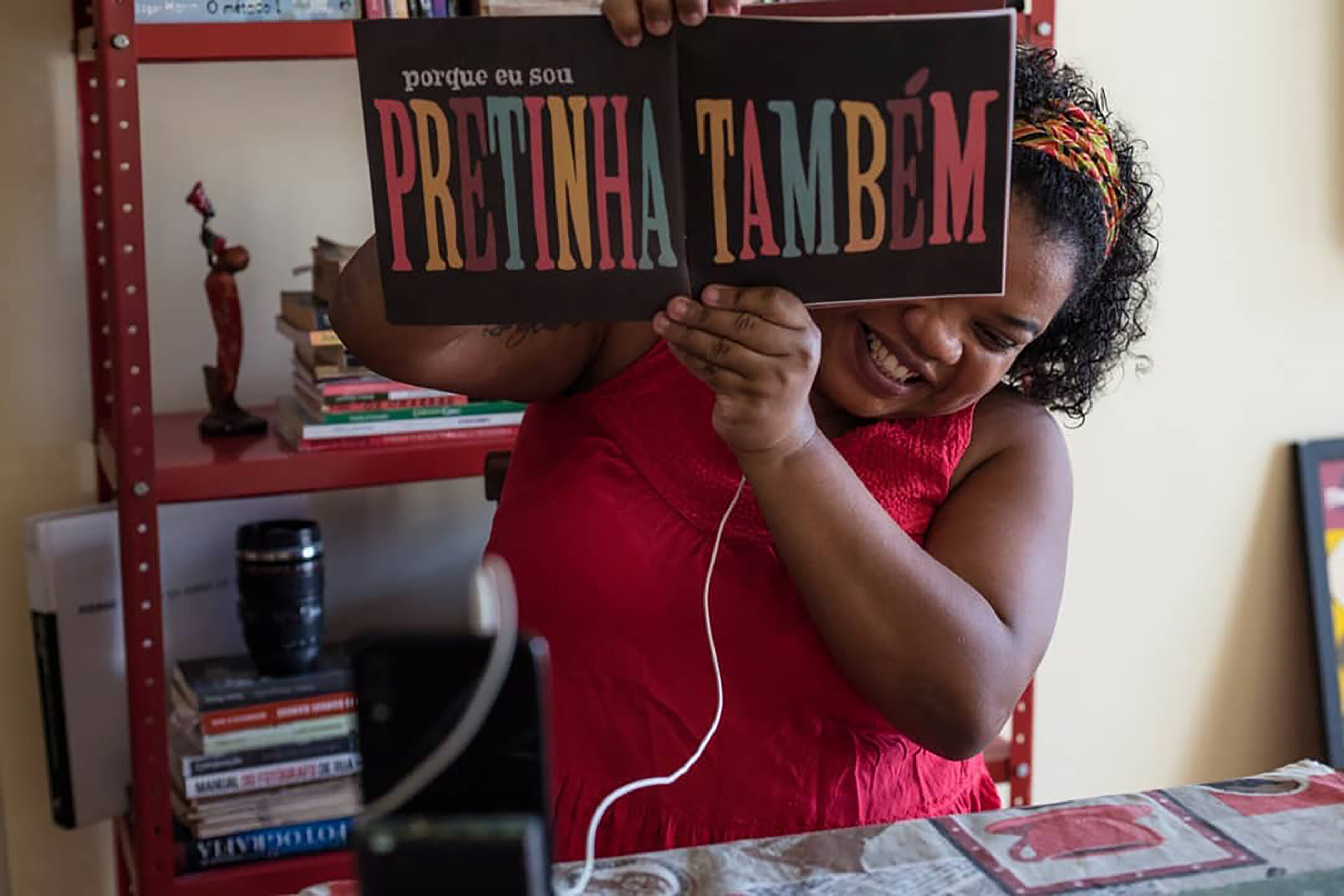

It was during this period of adversity that Carla Souza, an educator and Black storyteller born and raised in Rocinha, created the originally titled Mãe de Cria (Mother of Favela Natives) project. At that time, the initiative used a messaging app to create a welcome network offering pedagogical guidance for handling little ones confined at home.

“Mãe de Cria is a project that was born in the midst of global adversity: the coronavirus pandemic. We were all stunned before an invisible enemy. Two long years were dedicated to bringing educational and recreational support to families in social vulnerability. Thinking about the children of Brazil’s favelas, urban peripheries, suburbs, and underprivileged areas, we built a network of affection and Afrocentric education. However, change is part and parcel of the dynamics and nature of life.” — Carla Souza

Souza began offering activities to do at home, as the project emerged out of the demands of the pandemic. Between 2020 and 2022, she created activities with scrap materials for families to replicate, always based on Afro-Brazilian and African literature, and produced videos telling stories from Black children’s literature. Souza named the project Mãe de Cria because, as she explained, “‘mother’ [is] based on the profile of the majority of families in vulnerability in Brazil, which have Black women as the head of households, and ‘cria’ because it comes from an everyday expression used in favelas and urban peripheries to designate people who were born and raised there.”

The messaging group for friends became a profile on social media. With the return to collective spaces, Mãe de Cria left the screens and took to the streets, through lectures in schools, favelas, and NGOs. After it became a physical project, it expanded its scope even further and benefited children, primarily Black, across Rio de Janeiro state. During this journey, Souza has always kept children of the favelas and underprivileged areas as her focus, either through the network of affection already established or through Afrocentric education—both key methods of the initiative. Mãe de Cria taught children by centering Black perspectives, through narratives that emerge from the strength of people of African descent, both in and outside the mother continent.

Storytelling circles, workshops, and educational consultations for Black mothers were developed, influenced by the Adinkra philosophy of Sankofa—returning to the past to understand the present and build the future. As Souza explained, the project has an Afrocentric perspective, which “aims to help families become more autonomous and, at the same time, certain that we are a community and that, as a community, together we will learn the way back to our Mother Earth.”

Souza’s friend, psychologist Adilsilena Braz, known as Lena, started supporting Mãe de Cria over the Internet with livestreams. Braz says:

“My role was to think about and separate material. Then it moved on to storytelling [alongside] Carla, helping and mediating, and also developing activities: what we were going to offer the children, how we were going to approach things, with what material… I was a real partner and always had a psychological lens in contributing to the project.”

Ẹbí Project: ‘It Takes a Village to Raise a Child’

In 2022, Mãe de Cria changed its name and became Ẹbí Project. The change took place because the word “mother” weighs exclusively on women, placing the responsibility of educating solely on them. Souza decided to choose a name that reflected the reality that children are the responsibility of the entire family, and thus the Ẹbí Project was born. Coming from Yoruba, a language of the Niger-Congo language family and one of the most influential languages in Brazilian Portuguese, Ẹbí means “family.” However, not in the Western sense of the term: Ẹbí also incorporates an idea of community and the unity of a people.

In this regard, Souza believes that educating a child is the most beautiful and important mission of a community, of all of Ẹbí, and not just mothers. She summarized: “That is why the Ẹbí Project has as its motto the African proverb: ‘It takes a village to raise a child.’”

“Coming out of the pandemic, doing virtual activities stopped making so much sense with the return to collective spaces. The [social media] profile lost a little of its initial function, but the objectives became more defined… Nature is without doubt the greatest school we have and it wouldn’t be possible for it not to be present in the project’s ‘new face.’ Mother Africa has also been my guiding compass in this quest for an education that is increasingly Afrocentric. Finally, I couldn’t leave out the beauty of teaching in a circle, side by side. This concept is represented by the circular and rounded elements present in our new visual identity… The circle does not exclude, it is characterized by integration, horizontality, connection… This is how the Ẹbí Project is reborn. I affirm it as a rebirth because we are still Mãe de Cria in essence. However, due to the dynamics that nature imposes, it was necessary to rename this purpose of life and education.” — Carla Souza

Souza shared the color choices for the new identity as a way of recognizing her own physical and spiritual identity on the project’s social media. The colors—moss green, darker yellow, and brown—make reference to a very old and little-known deity: Onilé.

“Onilé, the First Earth Divinity according to Yoruba mythology, is a female deity related to the essential aspects of nature, to everything related to the appropriation of nature by man, which includes agriculture, hunting, fishing, and fertility itself. It all starts with Onilé, Mother Earth, both in life and in death. Onilé was also called Ilê, the home, the planet. Olodumare, father of the Divinity, said that everyone who inhabited the Earth should pay tribute to her, as she was the mother of all, the shelter, the home.” — Carla Souza

Cassia Divino is a historian and mother who takes part in the Ẹbí Project with her daughter Luiza. She comments on how the project impacts Black children, the difference it could have made in her own school life, and shares the importance of Ẹbí in her daughter’s education. She says that, as a child, she had no contact with Afrocentric stories and that for years she internalized the racism she experienced at school, perpetrated by other children.

“Carla Souza’s Ẹbí Project is a project that lights up the soil of our children, right? Mainly Black children, right? We know that we have a majority Black population in Brazil. Not to mention in Rio de Janeiro! And we see how much our children suffer in schools, right? Mainly Black children… These first experiences, this first contact with the collective, with society, is inside a classroom… And this school space is often traumatic for [Black] children… I studied in a private school… with few Black kids. I felt very harassed and, in fact, I was. I remember that whenever the subject was slavery, for example, I would die of shame. As I was the only dark Black person in the classroom, everyone looked at me… And so, with the upbringing I have given Luiza, I always bring her [to Ẹbí’s activities].” — Cassia Divino

Divino understands that the Ẹbí project provides tools for children and adolescents to fight racism, which is very present in their routines in different ways. That is precisely why she insists on providing Luiza with the many activities offered by the project. She lists numerous positive impacts on her daughter’s behavior and development after experiencing Afrocentric pedagogy and storytelling at Ẹbí. According to her, Luiza is different after participating in Souza’s project.

“The appreciation of Black culture within childhood in a playful, articulate, very well-thought-out, very personalized way… Carla studied Luiza’s age… she has been working in education for a long time, so we started having a conversation about what Luiza likes to do the most, what her activities are… Based on this information, Carla created a personalized project appropriate for Luiza’s age. This made a huge difference… We did various proposed activities, really playful activities, for her to get dirty, for her to have freedom, to help with cognitive development, motor skills, everything… Then, we realized that Luiza was a child who liked concentration games… She loves water games, those that require concentration and motor coordination. We were very surprised with everything these activities ended up developing in her… We realized that Luiza really is different after [taking part in the Ẹbí Project]… I realized that these concentration games made her calmer and she really spent a lot of time on the activity… Songs that are still in her memory today, African songs that tell our story, our ancestry, you know?” — Cassia Divino

Divino concludes by recommending the project to other Black children and affirming that representation matters. The effects of this Afrocentric experience in childhood are incredible and she sees it as very positive that the project is expanding and reaching a wider audience. She points out that the work of the Ẹbí Project falls perfectly within the guidelines established by Brazilian Law 10.639/03, which makes teaching African and Afro-Brazilian history mandatory. Therefore, what Ẹbí does is implement the law, which was supposed to be implemented in schools, squares, and public parks, ever since the law was introduced over 20 years ago.

“[The Ẹbí Project is] representation, strengthening, and experience, and all of this is important for children, you know? It makes a huge difference to us. I don’t hesitate to recommend it… I’m very happy that Carla is managing to continue this project in other ways, in other places, because we really need to do this if we want transformation… The work she has been developing with other families and in schools has been wonderful! It really is work that falls under Law 10.639/03, which makes it mandatory to teach African and Afro-Brazilian history in schools. This is very necessary… [in combating] harassment of Black children, right? And we have to treat education seriously, in a decolonial and Afrocentric way… as prevention… this prevents so many things that we have no idea about.” — Cassia Divino

Educator Carla Souza, with her 22 years of experience as a teacher, maintains the project through workshops, always in favelas and the urban peripheries, or through online consultations.

About the author: Gabriela Anastacia is a journalist, mother, and entrepreneur, not necessarily in that order.