Clique aqui para Português

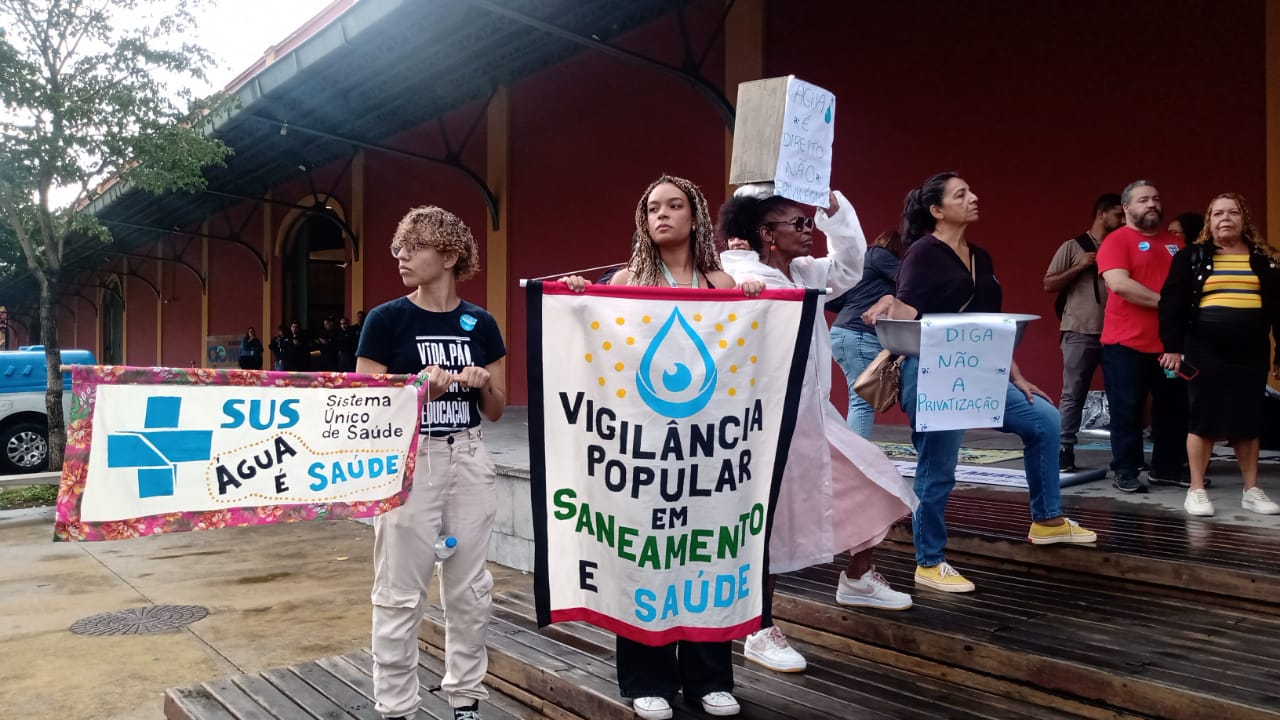

On March 20, just days before World Water Day, popular movements and members of civil society gathered in front of private water utility Águas do Rio to demand the right to water for favelas and peripheral areas across the state of Rio de Janeiro. The company has been responsible for water and sewerage services in the capital and 26 other municipalities since 2021. According to residents of various favelas in Greater Rio, however, the universalization and improvement of these services in favelas remain a distant reality.

Luiza Helena, a Social Work student at Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ) and a resident of the favelas of Complexo do Chapadão, in the city’s North Zone, expresses her frustration: despite paying R$60-70 (~US$10-12) per month for the utility’s services, she sometimes goes up to 20 days without water—a situation that has even kept her from attending class.

“The fact that they [Águas do Rio] say they provide a good service to the population is a lie. I’d like to see the contract Águas do Rio [has with the] community… You give them your address… your taxpayer ID, email—and [that counts as] an agreement that you have [had access to] your rights? Where is the contract between the [favela] consumer and the company? It does not exist. I believe they still have a lot to improve, you know? People are not asking for a favor—it’s a right. Sanitation, water—that brings life. Without water, we’ll die. How can anyone live without water? When you’re home, everything you do depends on water. There’s no doing anything without water.” — Luiza Helena

The protest took place two days before World Water Day, a date established by the United Nations General Assembly. Organized by the Popular Network for Sanitation and Health Monitoring, the event was supported by various partner organizations, including the Maré Museum; the nationwide Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB); Brazil’s national health institute, the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz); the Union of Water and Sewerage Service Workers of the State of Rio de Janeiro (Sindágua/RJ); and the Rio de Janeiro Climate Coalition. The gathering was attended by parliamentarians Yuri Moura and Dani Monteiro, as well as representatives from the offices of Tarcísio Motta, Dani Balbi, Renata Souza, and Thais Ferreira. Residents from the Vigário Geral, Complexo da Maré, and Complexo do Chapadão favelas also took part. No spokesperson from Águas do Rio came forwards to make a statement during the mobilization.

‘Water for Life, Not for Death’

The privatization of water distribution and sewage treatment services in Rio de Janeiro took place in April 2021, using the pandemic as cover to advance the process—despite global trends toward remunicipalization and widespread local opposition from both the public and industry professionals. On that occasion, the company Águas do Rio won the bid for CEDAE, taking over the management of these services for 10 million consumers.

In 2023, according to João Roberto Lopes Pinto, a Political Science professor at the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO) and the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio), the utility reported a net profit of R$614 million (~US$107 million)—an amount six times greater than the total allocated to all favelas under the Investment Plan for Non-Upgraded Irregular Areas (AINUs).

Also in 2023, according to the professor, the Consumer Defense Institute (Procon-RJ) recorded a 564% increase in complaints against the private utility compared to 2022, totaling 26,920 cases filed to assert consumer rights. Sharp increases in water bills, supply cuts, incorrect charges, and lack of access to services are among the reasons that led residents of Rio de Janeiro to take legal action against Águas do Rio.

In 2022, the Water and Energy Justice in the Favelas mapping, conducted by the Sustainable Favela Network, highlighted both the lack of access and the poor quality of the services provided by the utility.

Another popular mobilization for the right to water took place earlier in the week, on March 19, in front of the Rio de Janeiro Legislative Assembly (Alerj). The demonstration pressured public authorities to approve the creation of the Parliamentary Front in Defense of Water and a Public-owned CEDAE, since the state government has shown interest in opening CEDAE’s capital since December 2024. If this plan moves forward, the entire management of the service—from treatment to distribution—will be concentrated in the hands of Águas do Rio and other private utilities, such as Iguá.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

“ESG” for Whom?

Roberto Carlos de Oliveira, a member of MAB and a resident of Vaz Lobo, a neighborhood in Rio’s North Zone, explains that the neglect with which water supply and sanitation are regarded in the city is nothing new—but, according to him, it has worsened since privatization. He warns that Nature is already charging a price for this lack of commitment. Still, he emphasizes that climate change has been hitting the poorest communities and favelas the hardest.

“Several studies indicate that Rio de Janeiro will be the state most affected by climate change in the coming years. We have a highly populated state, often in areas abandoned by the State, along riverbanks… Many buried rivers. The history of urban development in Rio is a history of erasing rivers, of covering them with asphalt… We’re facing a ticking time bomb here in Rio, that’s the truth. And water is central to all of this, because you can’t tackle flooding, landslides, and overflowing without basic sanitation. Our sanitation system was built over decades, centuries, and then handed over to a private company that built nothing. Since privatization, it’s been taking it over and running it into the ground. Just last year, around 20 water mains—responsible for transporting water—broke in Rio and the Baixada [Fluminense]. One of them even caused a fatality in Rocha Miranda [Marilene Rodrigues, who was 79 at the time]. [In the middle of the night,] the [Águas do Rio] water main blew up, tore down her home while she was sleeping inside, and she died.” — Roberto Carlos de Oliveira

Ver essa foto no Instagram

For Caroline Rodrigues, a Social Work professor at UERJ and a resident of Botafogo, in Rio’s South Zone, the company contradicts itself when it claims to uphold ESG principles—the acronym for Environmental, Social, and Governance, used by some corporations to signal their commitment to responsible practices. According to the professor, Águas do Rio’s performance in terms of service quality and universal access falls extremely short of the values the acronym stands for.

“There’s no connection between sanitation, water, and climate. For them, it’s just any old city service for those who can afford to pay. This connection has mostly been built by us [people’s movements] despite them having this ESG discourse. We currently know of residents who used to have access to water through alternative sources, which the company has been making difficult or even downright preventing [access to waterfalls and wells that have been used sustainably by local people for generations]. And this is just one example of how this privatized model deepens deprivation and worsens the precarious conditions around water use.” — Caroline Rodrigues

Cida Rodrigues, from the Ecoa Maré socio-environmental project and the Maré Museum, explains that the coming together of movements is essential to overcoming the denial of the right to water and preventing it from continuing to devastate favela and peripheral communities in the future.

“Without water at home, people have to grab their buckets, their containers, and collect water however they can. It’s a complete lack of respect for the population… And then we understand that it’s by joining forces, by standing with those who understand this need… by being part [of these mobilizations, that we can move forward]. We have to stay together. We won’t get anywhere alone. Since water is an issue that affects everyone, everyone needs to be in this together.” — Cida Rodrigues

Although Brazilian legislation promotes and guarantees universal access to water, the fight to ensure these laws are fully enforced still has a long way to go. Bruno França, a former resident of Morro dos Macacos and a member of the Popular Network for Monitoring Sanitation and Health, argues that the right to water must be safeguarded as a public good.

“Water is a resource that must be guaranteed as a public good, so that it doesn’t soon fall completely under the control of corporations—accessible only to those who can afford it. The connection between the water crisis and the climate crisis is very strong, and it needs to be increasingly emphasized. That’s why we defend water as a common good. It cannot be subordinated to a business. It cannot be a source of profit. It has to belong to the people.” — Bruno França

Under the law, the right to water is universal and recognized as serving the common good. It is essential for health, nutrition, and the promotion of social well-being. In ongoing vigilance to ensure this right is upheld, popular mobilization will continue to fight for the phrase Lata d’água na cabeça—a reference to the historical practice of carrying heavy water containers on one’s head—to remain nothing more than a line from the famous samba performed by singer Marlene in 1952, and never again a reality for the favelas and peripheral areas of Rio.

Laws That Guarantee or Address the Right to Water:

-

Law No. 14.898/2024, which establishes national guidelines for the Social Water and Sewage Tariff (a fund for the universalization of access to water), and prioritizes access to drinking water for low-income families.

-

Decree No. 7.535, which creates the National Program for the Universalization of Access to and Use of Water, also known as “Water for All.”

-

Law No. 9.433/1997, which establishes the National Water Resources Policy—one of the key instruments guiding water management in Brazil—aims to ensure water availability, quality, and efficient demand management.

About the author: Amanda Baroni Lopes is a journalism student at Unicarioca and was part of the first Journalism Laboratory organized by Maré’s community newspaper Maré de Notícias. She is the author of the Anti-Harassment Guide on Breaking, a handbook that explains what is and isn’t harassment to the Hip Hop audience and provides guidance on what to do in these situations. Lopes is from Morro do Timbau and currently lives in Vila do João, both favelas within the larger Maré favela complex.