Clique aqui para Português

The mayor of Rio de Janeiro aims to transform the city’s Port Region into a technology hub. Newly reelected, Eduardo Paes plans to turn the area into a hotspot for high-tech and innovation companies. Named Porto Maravalley, the project is a nod to Silicon Valley. The development of this hub, focused on attracting big tech, is part of the broader Porto Maravilha (Marvelous Port) mega-project, which involves investments worth billions.

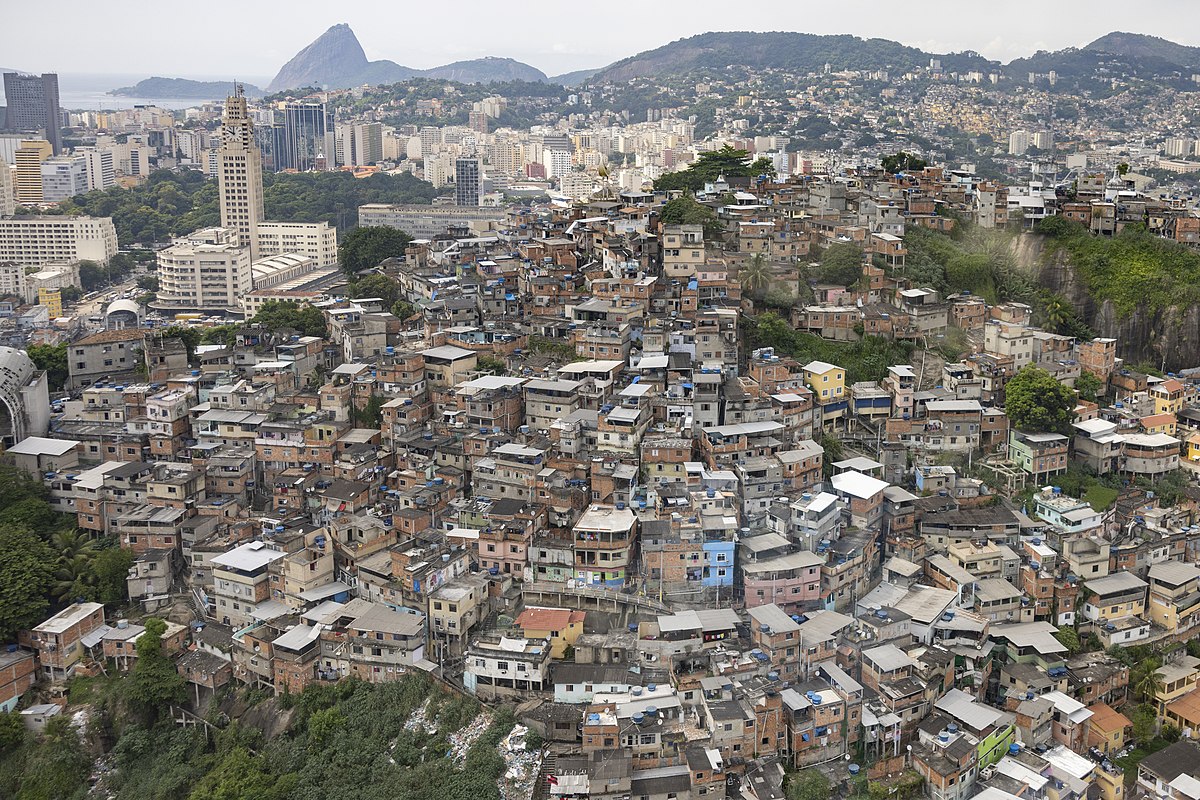

The Innovation Hub, which includes both physical and virtual spaces, already hosts some of the world’s biggest tech companies, such as Google and Meta (the parent company of Facebook and Instagram). The hub, which will bring together major corporations, students, and startups, was officially inaugurated on April 11 in an event attended by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the mayor, and business leaders. However, residents of nearby favelas report that they have little knowledge of the Porto Maravalley project and its potential impact on their communities.

Little Africa: History and Present Cleansing and Gentrification

The Rio de Janeiro city government has a longstanding history of implementing urban changes in the downtown area. In 1903, Mayor Pereira Passos introduced the “Bota Abaixo” (“Tear It Down”) policy, which resulted in the forced eviction of downtown residents to reshape the region’s image. Tens of thousands of people were uprooted from their homes in a process aimed at socially “cleansing” the city center.

The region has been undergoing continuous transformations in recent decades, with developments reshaping what is also known as Little Africa. However, the new infrastructure rarely addresses the needs of local residents in the neighborhoods of Saúde, Gamboa, Santo Cristo, Morro da Providência, Morro do Pinto, and Morro da Conceição. Recent projects include the construction of the Light Rail System (VLT), the Museum of Tomorrow, and the Rio Museum of Art (MAR). These public attractions have brought more visitors to the area, spurring an influx of new residents and driving up prices. Meanwhile, long-term residents have endured years of disruptive construction, seeing few tangible benefits to their daily lives.

The impacts of these changes are voiced by Miriam dos Santos Generoso, project coordinator at Casa Amarela Providência, who was born and raised in Brazil’s oldest favela, Providência. “I didn’t even know about Porto Maravalley,” she said, explaining that she only learned about the project while seeking information for this RioOnWatch article. Despite being a leader at a prominent institution in Morro da Providência and having lived in the Port Region for 23 years, she was neither consulted nor informed about the City’s implementation of the project. This situation highlights the glaring lack of basic participation from those who are integral to the living history of a territory vital to Brazilian memory and heritage.

Many try to understand why the City has not engaged in dialogue with local residents and organizations regarding Porto Maravalley. This question has shadowed the Porto Maravilha projects since construction began during the pre-Olympic period.

“When I moved in, I settled in the buildings in Saúde. Back then, there was no Porto Maravilha; the Port Region was still very different from what it is today. We started to notice some changes. In 2006, my family bought another apartment in Providência, and since 2018, I’ve been gaining a deeper understanding of this place [as a resident]. My sense of belonging has developed since 2018, rooted in the construction of identity and in recognizing the place where we live, which reflects who we are… [The urban planners and politicians driving these transformations] often overlook the people who live in the area, gradually suffocating us.” — Miriam dos Santos Generoso

For her, a complex of real estate developments of this nature could bring benefits to the area, but it seems that it will not. It was not designed with the needs of the favelas in Little Africa or their residents in mind. On the contrary, it reinforces the divide between those who have historically lived there and the newcomers migrating to the Port Region after the urban interventions. Projects and policies like Porto Maravalley aim to gentrify the area by attracting a new demographic of residents. As a result, they do not consider the longstanding and vulnerable communities of the surrounding areas in their conception.

This situation creates a wide gap between a middle class increasingly attracted to the neighborhood by the city’s urban policies and a socioeconomically vulnerable population, primarily made up of long-term residents. This predominantly Black community is facing growing pressure to relocate and is gradually being replaced by white, middle-class residents. Abandoned factories and buildings that could have been repurposed to ensure housing rights and foster a sense of belonging for the local population have instead become tools of real estate speculation. These spaces now host art galleries, niche events, and other commercial ventures that contribute to the gentrification of the area.

Generoso points out that this process has driven up rental prices in the favela, which have surged since the early mega-events construction began. According to her, this negatively impacts local identity.

“As these developments come in, they erase the historical context of this territory. For example, it’s getting more and more expensive to live in the favela, and we struggle to find houses to rent. Prices are rising, and the area is becoming whiter. This gentrification process is pushing Black residents to the North Zone and other areas.”

Ellen Costa, a cultural manager who was born and raised in Providência, notes that the favela has been negatively impacted by the ongoing construction in the area. Since the introduction of the VLT, the effects on residents’ lives have been significant. “We go down [the hill] to work, but the area doesn’t connect with what happens [up here] in the favela,” she emphasizes.

“The VLT is the only option of public transportation within the neighborhood; the bus lines no longer operate. Naturally, this impacts people’s ability to commute to work. For example, today you [have to] go to Central [train station] to take the subway. Depending on which side of the favela you live on, you might have to walk quite a distance to reach the subway and head to the South Zone. Or you have to go to [bus] Terminal Gentileza. If the bus is the only option to get to work, it forces people to leave home much earlier, which ultimately affects their quality of life.” — Ellen Costa

Like Costa and Generoso, Eron Cesar dos Santos, 57, was also unaware of the Porto Maravalley project. A biology teacher and capoeira master born and raised in the favela, he shared his thoughts and expectations.

“I’m hopeful that it will revitalize this region and expand job opportunities for the local population. I hope the positive impacts outweigh the negative ones… that it brings investments in infrastructure, water, and electricity distribution.” — Eron Cesar dos Santos

In a statement, the City of Rio, through the Carioca Company for Partnerships and Investments (CCPar), “informs that the Porto Maravalley project is an initiative of the City of Rio that integrates education and innovation within the Porto Maravilha area. The municipality has invested in acquiring equipment and offering subsidized housing for students attending the National Institute for Pure and Applied Mathematics (Impa) from across the country.”

The statement further notes that “in addition to Impa, the space is home to the Innovation and Technology Hub, managed by Rio Energy Bay. The investment in the management and administration of the site is privately funded, incurring no costs for the municipality. Impa is 100% free and receives financial support from the federal government through the Ministry of Education (MEC) for its undergraduate programs.” The city government did not specify whether there is any component of the project aimed at the favelas in Little Africa, which have been affected by urban changes in the region for nearly two decades.

About the author: Igor Soares was born and raised in Morro do Borel and has a journalism degree from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). He currently contributes to #Colabora and works as a freelancer. He has experience covering topics related to cities, human rights, and public security, having previously worked at Estadão, Portal iG, and produced reports for Folha de São Paulo.