Clique aqui para Português

“There are days when we just want to cry, to stay in bed, and not speak to anyone because we don’t have our children to hug anymore.” — Gilsara Mendes, mother of Thiago

The story of Gilsara*, a resident of Jacarezinho for 24 years and mother of three children, is a striking portrait of the reality imposed by armed violence in favelas. Her oldest son, Thiago*, was killed by the police during the Jacarezinho Massacre on May 6, 2021.

Besides the pain of her loss, Gilsara lives with the challenge of raising her other children, Jorge and Saulo, in an environment characterized by insecurity and the constant threat of new conflicts. The mental health of the whole family is fragile and access to quality public health services is difficult.

The Jacarezinho Massacre, which resulted in the death of 28 people, including Thiago, is an example of the government’s failure to guarantee public security and the right to life of its citizens. The community lives under the constant fear of violent police operations, which generate an environment of terror and helplessness.

“For New Year’s, we thought about organizing something. I was going to my sister-in-law’s house, since she always puts something together. She was having a barbecue and invited us over, but we weren’t able to leave our home. My son Jorge had been able to go out earlier and was at a friend’s house. But me, my husband, and my younger son were stuck at home due to a gunfight that broke out at around 9pm, which made it unsafe to go out.” — Gilsara Mendes

In spite of complaints circulating on social media and on the news about residents’ rights being violated, constant police operations in Jacarezinho during the month of January 2024 created a tense atmosphere due to gunshots and abuses of authority, particularly around New Year’s.

Besides that, since Thiago’s death in 2021, what should have been happy moments have become sad memories for Gilsara:

“[Thiago] loved parties, highlighting his hair and going out to have a good time with his friends. He’d stay home with us until midnight and then go out to dance parties. All the violence committed by the State falls entirely on the family, because the authorities take no responsibility for caring for us after the police operations and the violations they perpetrate.”

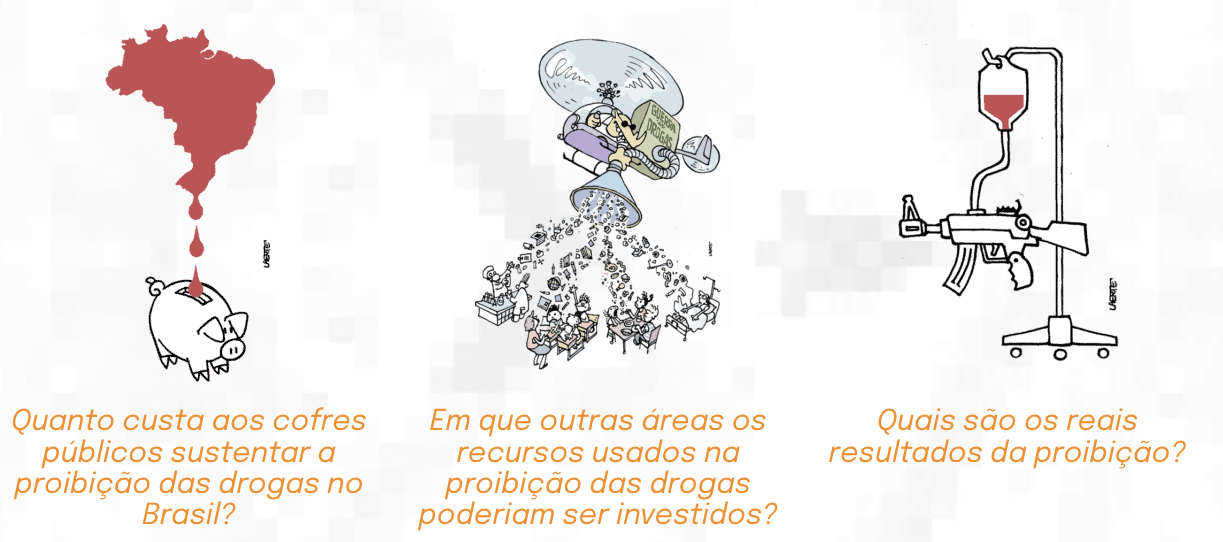

Rio de Janeiro’s “antidrug policy” is a failed war, causing public insecurity by focusing on police operations in the favelas instead of investing in intelligence capabilities. The more money invested in arms, the more the public suffers from police violence. In 2023, an unprecedented study called Favelas as Target Ranges: the Impact of the War on Drugs on the Economy of the Territories, published by the Center for Studies on Public Security and Citizenship (CESeC), showed that police actions in favelas have caused losses of at least R$14 million (~US$2.5 million) per year to the residents of these communities, not to mention the countless more serious consequences, like deaths and the destabilization of the survivors’ lives. All of this is avoidable. Those who suffer most from this misguided policy are people unconnected to organized crime. These actions destabilize the economic life and physical and mental health of families and their neighbors’.

“Not everything can be resolved with guns and by the police invading favelas, treating socially vulnerable people as criminals.” — Gilsara Mendes

The Fogo Cruzado Institute conducted a seven-year study on police violence in Rio de Janeiro, collecting data on children and youth who were victims of police operations. Between July 5, 2016, and July 8, 2023, 601 children and adolescents were shot in the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region. Adolescents accounted for 78% of the victims (231 killed and 237 wounded). Among the 133 children who were shot, 36 were killed and 97 were wounded. At least 63 children and adolescents were shot while inside their homes (37 killed and 26 wounded). Twelve were shot inside schools, with one killed and 11 wounded. Seven others were shot while on their way to or from school. Police actions and operations were the main cause of death among children and adolescents during the seven years of the study. Women suffer the most from the pain of losing their children, as historically they have been responsible for maintaining the emotional and economic stability of their families.

Health at Risk: Firearms and Chronic Illnesses

In 2017 and 2022, CESeC conducted unprecedented research as part of the study Drugs: the cost of prohibition, confirming what is already evident regarding security, justice, education, health, and territory. 1,500 residents from six different regions of Rio de Janeiro were interviewed. Three areas were identified as the most affected by gunfights involving State agents: Complexo da Maré, Vidigal, and Manguinhos. It’s important to highlight the racial aspect of the findings below: the population in the favelas is predominantly Black, with many already living in vulnerable conditions. 66.2% of homes in favelas are occupied by Black people.

The study shows that in areas with more frequent police operations, at least 51% of the people interviewed suffer from physical or mental disorders such as arterial hypertension, chronic insomnia, anxiety, or depression. In regions with fewer cases of armed conflict, this percentage drops to 35.9%. In areas with constant conflict, the risk of residents developing hypertension is 42%, and 73% for chronic insomnia. Depression affects 29.6% of people aged 18 to 45 in areas with more frequent gunfights, while in regions with fewer cases, 15.7% of residents suffer from this condition.

“I am physically weak and debilitated. I have diabetes, high blood pressure, and anxiety attacks. We go on living through these situations again and again which leaves us even more tired.” – Gilsara Mendes

The study also shows that at least 30% of residents exposed to armed violence report experiencing immediate negative effects during gunfights, such as sweating, insomnia, tremors, and shortness of breath, with 43% reporting an accelerated heartbeat when hearing gunshots close to their homes.

According to the Municipal Health Secretariat, 445 health units were closed in 2022. The CESeC study shows that in communities more exposed to State violence, at least 59.5% of interviewees reported that, at some point, these units were closed due to security risks and police violence. In favelas less exposed to violence, the number of closures dropped to 13%. Approximately 26% of residents in regions most affected by armed conflict had to postpone seeking health care, while in less affected regions, only 6% had to delay seeking care. Among health professionals, in the more conflict-affected areas, 31.6% of residents reported that they stopped working because of gunfights. In areas with less violence, this number was below 12%.

The annual cost of closing health units amounts to over R$300,000 (~US$53,600) in public spending, plus the costs of treating people who become ill due to this necropolitical policy. The annual State investment in treating patients with arterial hypertension and depression can vary between R$69,000 and R$95,000 (~US$12,300 to US$17,000, based on 2022 figures). Yet, so many people are killed, wounded, or made ill by state violence. So much money spent, with no concrete results.

The Impact of Silence

The fatalities resulting from police operations extend beyond the immediate victims. Gilsara reports the death of at least three mothers and one father who couldn’t bear the pain of losing their children in the Jacarezinho Massacre. In January 2022, one year later, Dona Rosangela*, the mother of another victim, developed depression and anxiety attacks, and other health problems that ultimately led to her death. In December 2022, Dona Lúcia dos Santos*, another grieving mother, suffered from anxiety and depression crises, and due to the lack of timely medical care, died on the way to the hospital. Between November and December 2023, Dona Denise Miranda*, also the mother of a young man killed in the massacre, became depressed and socially isolated, which worsened her health and resulted in her death.

In March of 2023, Mr. Jorge da Silva*, father of one of the victims and husband of Dona Angela*, also succumbed to the emotional toll of the tragedy. Having sunk into a deep depression, he tirelessly searched for his son, wandering through the favela at all hours of the day and night. During one of these searches, he was shot in the chest during a police operation and died.

“These days, I’m trying to get back to some parts of my routine, to take care of myself a little, to give a bit more attention to my children. After Thiago’s death, we were completely lost. My 17-year-old son, Jorge, for instance used to be the type of boy who followed everything online and stood up for everything and everyone. After his brother died, he couldn’t focus on his studies and has repeated his first year of high school three times. Saulo, my ten year old, has mild autism, and suffered a lot after losing his brother. After the massacre and my son’s death, I’d just walk around the house crying, unable to give my other children the attention they needed. Now, I am looking for assistance and support with my physical and psychological health.” — Gilsara Mendes

*The names in this article are fictitious in order to protect the privacy and security of the interviewees.

About the author: Ramon Vellasco is a freelance photojournalist and reporter, born and raised in Vila da Penha. He focuses on issues related to human rights, culture, education, diversity, and marginalized social groups, primarily working in peripheral, favela, areas.