This article is the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.

Introduction to Brazilian Whiteness: Why Salvador, Bahia?

Salvador, the capital of the Brazilian state of Bahia, is home to a white elite that still hails from the nation’s colonial past. It is the most traditional white elite in the country.

Brazil’s first capital city, founded in 1549, Salvador maintained its status until Rio de Janeiro became capital in 1793. Salvador was also the Portuguese Imperial Court’s first harbor when the Portuguese royal family fled to Brazil, their largest colony, after Napoleon’s conquest of Portugal in January 1808. However, in March of that same year, the Court moved to Rio de Janeiro, making the city—which had become Brazil’s colonial center only 15 years earlier—also the capital of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and Algarves, and thus taking the place of Lisbon as the power center of the Portuguese Empire. Once he settled in Rio, Dom João VI left behind Salvador’s elites, who represented a traditionalist, conservative colonial elite that fiercely defended its character as Portuguese, noble, European, white, and slaveholding.

The city of Salvador and the state of Bahia were the most resistant to Brazil’s independence. While, historically, Brazilian Independence Day is recognized as September 7, 1822, independence was celebrated in Bahia only on July 2, 1823. This almost one-year difference is due to the resistance of Bahia’s white elite to cut their affiliation with the Portuguese Crown and to reject its European character.

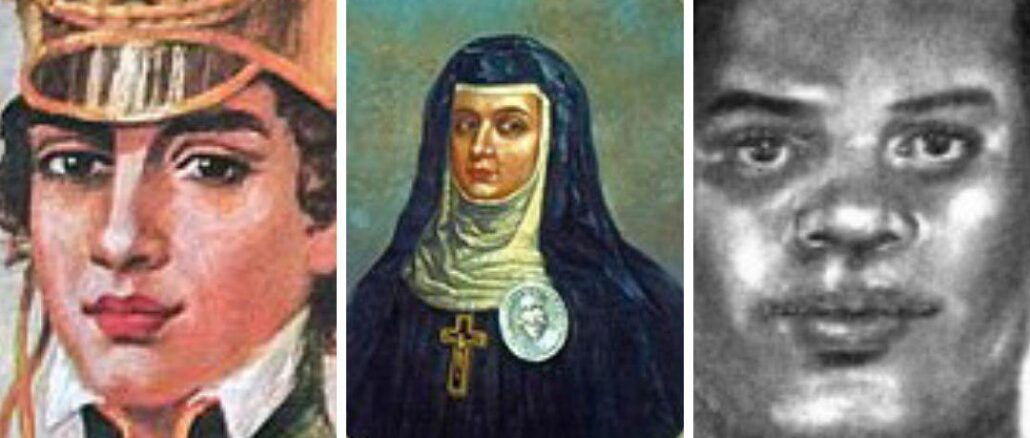

Only the mass participation of the people, of the indigenous and black populations, and of women—such as Maria Felipa, Joana Angélica and Maria Quitéria—led the Portuguese troops to finally leave Bahia in 1823, what Bahians genuinely consider Independence Day. It was not by the fighting hands of the noblemen, of the local white elite, that the colony ended in Bahia, a process quite different from what happened in other Brazilian provinces at the time.

From the above Facebook post:

A black person and a poor woman, Maria Felipa is hardly ever remembered for her deeds.

Born a slave, no one knows the exact year of her birth. When released from slavery, she accepted it as life’s greatest gift. A resident of the island of Itaparica, she worked collecting shellfish from an early age. She learned capoeira to fight and defend herself.

Maria Felipa wanted a Brazil free from the Portuguese, who had been responsible for the enslavement of the African people and their families. After Dom Pedro I’s Proclamation of Independence, some Portuguese nationals decided to attack with weapons. Maria Felipa participated in defense of Independence. At first, she spied the comings and goings of the caravels and would then take a raft to Salvador, where she passed the news on to the Liberation Movement Command.

Tired of just keeping watch, she decided to enter the fight. She knew that a fleet of 42 vessels was preparing to attack the fighters in the Bahian capital. So, Maria Felipa called 40 of her female companions to take action.

This group of women seduced most of the soldiers and commanders. After taking them to an isolated spot, they waited until the soldiers started taking their clothes off. When the men were finally naked, Maria Felipa and her group beat them with cansanção (Jatropha Urens, a plant that causes a terrible burning sensation and leaves burns on the skin), and then set all the vessels on fire.

This action was decisive for the victory over the Portuguese in Salvador, allowing troops coming from the Recôncavo region to enter the city under the people’s applause on July 2, 1823.

But Maria Felipa still did more, she continued to lead an armed group and fight for people’s rights even after the war ended.

During the first national flag raising ceremony at the Fortress of São Lourenço, in Ponta das Baleias, after the Portuguese were defeated for good, Maria Felipa and her group invaded the fishing structures owned by a wealthy Portuguese man, Araújo Mendes, and struck a guard, showing that the struggles of Itaparica’s people were not over.

Admired by the people, Maria Felipa continued her life as a shellfish gatherer and capoeirista. She died on January 4, 1873.

She is cited by some authors, such as Xavier Marques in the novel Sergeant Pedro, and by historian Ubaldo Osório in The Island of Itaparica.

In the colonial period (1530-1822), Salvador and Rio de Janeiro were Brazil’s main slave ports. During these first three centuries, approximately 1,200,000 enslaved Africans landed in Bahia’s capital. In the same period, 797,924 enslaved people landed in Rio de Janeiro. However, in the postcolonial period, from independence in 1822 until slavery’s abolition in 1888, the influx of enslaved people increased, especially to Rio. Consequently, Rio de Janeiro alone would end up receiving approximately 2 million enslaved Africans throughout its history [more than three times the total taken to the United States].

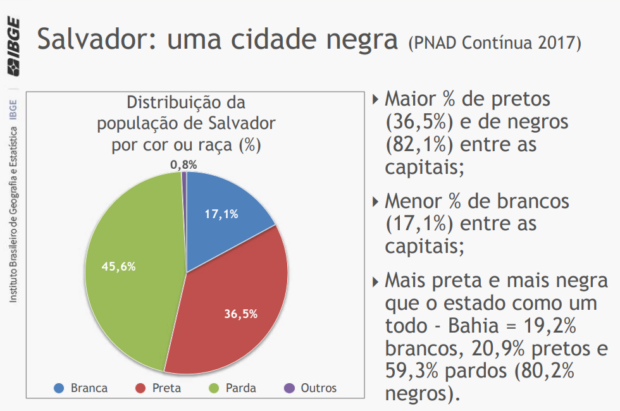

Therefore, although Rio became the largest slave port in all of history, Salvador was colonial Brazil’s first, longest lasting, and largest slave port, and maintained its position as the center of the country’s slave trade longer than Rio de Janeiro. According to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), Salvador is the Brazilian city with the largest black population: 82.1%. It is the blackest city not only in Brazil, but outside of Africa.

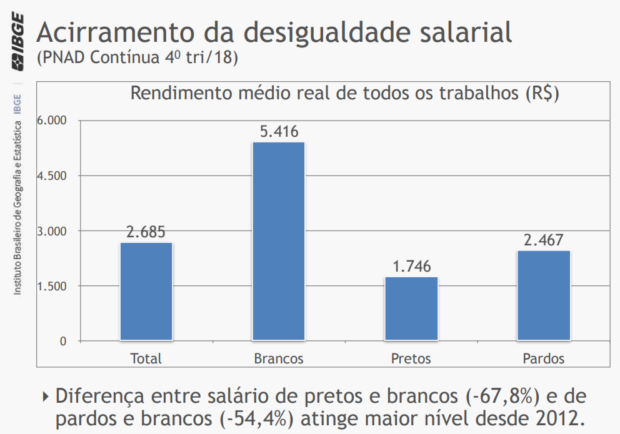

Salvador is, to this day, the most classic den of whiteness: it concentrates the smallest and most colonial white elite in the country. Making up, approximately, 17% of the population, Salvador’s white contingent is privileged with the largest wage inequality by skin color in the country, earning 67.8% more than the black population according to IBGE. In addition to these racial and economic gaps, racial inequality also impacts the chance of survival. In various neighborhoods, without any contestation, State agents continue to threaten and kill black bodies, as did bush captains in the era of slavery.

With a highly truculent police, the state of Bahia is only second to the state of Rio de Janeiro, champion of murders committed by the Military Police, with 1,239 deaths recorded in 2020. The Military Police of Bahia (PMBa), in turn, ended the lives of 1,137 people, even ahead of the Military Police of São Paulo, which perpetrated 814 homicides during the same period. It is important to point out that the population of the state of São Paulo is three times larger than Bahia’s. Another frightening fact: in 2020, all victims of the police in Bahia were black men. Meanwhile, others live on with their privileges.

Do You Know What White Privilege Is?

On the last Sunday in October, 2021, in the neighborhood of Farol da Barra, in Salvador, Bahia—the blackest city in Brazil, nicknamed “Black Rome”—I, a light-skinned black woman, approached white people and asked them questions. When asked: “Do you know what white privilege is?”, most were embarrassed. The expression “white privilege” causes some discomfort. I heard answers such as: “I don’t want to be part of the article, you’d better talk to a black person,” or “I’m not a racist,” or “I’m not white, my grandmother was indigenous!” and “What is this?”

On the last Sunday in October, 2021, in the neighborhood of Farol da Barra, in Salvador, Bahia—the blackest city in Brazil, nicknamed “Black Rome”—I, a light-skinned black woman, approached white people and asked them questions. When asked: “Do you know what white privilege is?”, most were embarrassed. The expression “white privilege” causes some discomfort. I heard answers such as: “I don’t want to be part of the article, you’d better talk to a black person,” or “I’m not a racist,” or “I’m not white, my grandmother was indigenous!” and “What is this?”

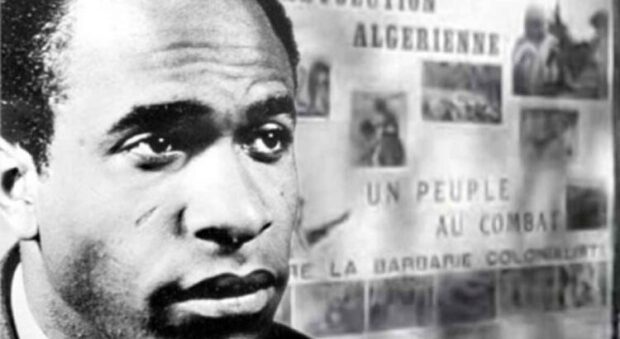

The term white privilege, or “whiteness,” is not recent. Its usage began in the 1950s by the likes of psychiatrist Frantz Fanon, author of Black Skin, White Masks, and gained prominence in the 1990s in the United States. According to anthropologist Izabel Accioly, the expression serves to designate a group that holds white privilege, both material and symbolic power. The anthropologist goes on to say:

“Often, when having contact with the term [whiteness] for the first time, people may think that it refers to the social group of white people, a mere synonym. But that’s not all. It also represents the entire power system that this group has [access to].”

Policing in “Black Rome” and Whiteness

That which is synonymous with fear for the black majority of Bahia’s population means safety and protection for the white population. The sene of peace written all over the faces of those who do not have to worry about the Military Police’s violent actions is the clearest face of Brazilian white privilege. After all, even if the white person does not have a lot of money, they have the symbolic privilege of being seen as superior, of not being perceived as a suspect all the time.

While black people are arrested, humiliated, and killed every day in Brazil, victims of criminal selectivity and racial profiling, white people have “a kind of pre-approved credit” or, as Accioly explains, just because they are white, they are consistently exempted from being liable to society and to the Brazilian State.

Matheus Felipe Tavares, 29, a teacher, recalls when he came to understand white privilege. About ten years ago, when he was approached by police at a bus stop on Avenida Bonocô, near his home in Cosme de Farias, one of Salvador’s poor neighborhoods, he clearly observed whiteness at play. He reported:

Matheus Felipe Tavares, 29, a teacher, recalls when he came to understand white privilege. About ten years ago, when he was approached by police at a bus stop on Avenida Bonocô, near his home in Cosme de Farias, one of Salvador’s poor neighborhoods, he clearly observed whiteness at play. He reported:

“It was Sunday. My eyes were bloodshot, like embers, since I’d just smoked a joint. I was maybe 17, 18 and wasn’t at all well dressed. There was another young man waiting for the bus next to me who appeared normal and who was wearing simple clothes, like mine… One thing that struck me that day, was that I thought the police would frisk me because I had a joint [in my pocket] and you could see the outline clearly in my pants, and because of my eyes. But, instead, they roughed up the kid really badly while a policewoman pushed me away from the scene with her forearm. They searched the young man and let me go. Our difference [between me and the other guy] was that I’m a white man and he was a dark-skinned black man.”

Fully aware of the reason behind this story’s outcome, Tavares states that racism was the precise reason why the PMBa did not find him suspicious. Tavares could not follow up on what happened to the young black man because he was removed from the scene by the police. Even being poor and carrying marijuana in his pocket, the teacher suffered no reprisals from the Military Police due to his color privilege, as explained by Accioly. The suspect was the other, even if the evidence pointed to Tavares, the white man.

Whiteness: A Device of Structural Privilege

Unlike Tavares, Bahian singer Merjory Kênia has been subjected to practices which white people would seldom experience. In 2007, the young black woman went to Salvador to take the college entrance exam for Oceanography at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA). Kênia was accepted and became the only black woman in her class. But the country girl, born and raised in small towns, with populations of less than 30,000 inhabitants, was harassed by racism and white privilege in the capital of Bahia, home to over 3 million people. In 2011, Kênia was also accepted to UFBA’s School of Music’s singing course, where she often noticed the professors’ preference for picking white students to sing solo parts.

Unlike Tavares, Bahian singer Merjory Kênia has been subjected to practices which white people would seldom experience. In 2007, the young black woman went to Salvador to take the college entrance exam for Oceanography at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA). Kênia was accepted and became the only black woman in her class. But the country girl, born and raised in small towns, with populations of less than 30,000 inhabitants, was harassed by racism and white privilege in the capital of Bahia, home to over 3 million people. In 2011, Kênia was also accepted to UFBA’s School of Music’s singing course, where she often noticed the professors’ preference for picking white students to sing solo parts.

Despite the obstacles of racism, Kênia managed to graduate; she is an opera singer and teaches voice in music schools in Curitiba, where she now lives. Asked about racism in the majority white capital of the southern Brazilian state of Paraná, she recalled that the city had a 65% increase in the number of deaths of black people in 2020 during the pandemic. She was emphatic:

“I’ve seen white people who’d rather stand than sit next to me on the bus. I know that because as soon as there’s a free space next to another white person, they’ll sit down. When I walk into a store, I always see security guards communicating through their walkie-talkies; I see how the saleswomen look at me suspiciously, and approach me thinking I’m going to steal something.”

This is no different in Salvador or in any other Brazilian city. The reason Kênia knows, feels and understands these damning and suspicious looks from saleswomen and security guards is mainly due to a situation she faced in Salvador, but which is a frequent narrative for male and female black youth across Brazil:

This is no different in Salvador or in any other Brazilian city. The reason Kênia knows, feels and understands these damning and suspicious looks from saleswomen and security guards is mainly due to a situation she faced in Salvador, but which is a frequent narrative for male and female black youth across Brazil:

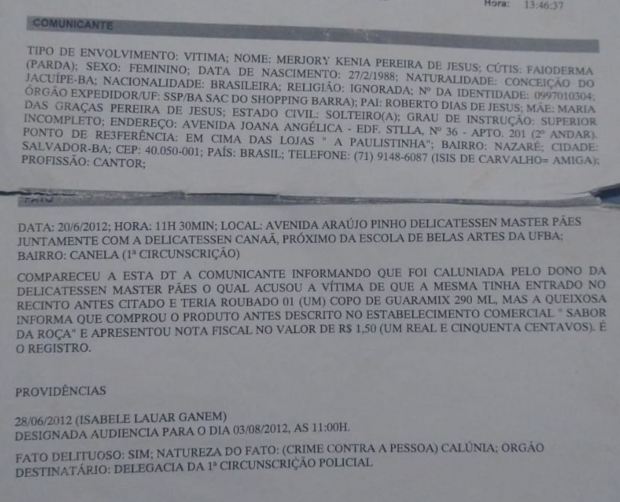

“One day, after work, I walked into a market and bought a natural guaraná, which at the time cost R$2, and then I walked into the Master Pães bakery, in the neighborhood of Canela, near where I lived, with the open container in my hand. I could not find what I was looking for there, so I went into another bakery, named Canaan, when I was completely taken aback by the screams of a man accusing me of having stolen the guaraná. I was humiliated in that place. No one defended me, even though I proved that I had bought the product earlier with a sales receipt.”

Kênia went to the police station to press charges, and the white chief of police discouraged her from doing so, claiming it “wouldn’t amount to anything.” Kênia said:

“I read the statement given by the bakery owner and he had not denied the situation. As always, the female chief of police was white. I felt like crap. I couldn’t afford a lawyer. The baker was a rich white man, and I’m sure he had lawyers. I’ve never forgotten this day. I was humiliated and wronged for being black.”

In addition to suffering these and other crimes of racism, Kênia points out moments when she went to the mall with a former university classmate: “She was always waited on, while I had to wait for someone who did not look at me with suspicion to come talk to me.”

The Inheritances of Colonialism: Whiteness and Material and Symbolic Privileges

Whiteness is a material and symbolic system that affects black people in various aspects, including professional. The not hiring of black people, especially for leadership positions, is closely linked to whiteness and racism. The IBGE’s Continuous National Household Sample Survey (Continuous PNAD) shows specific data on unemployment in Brazil for 2020, during the pandemic. According to the survey, black people represent 72.9% of the country’s unemployed, a total 13.9 million people. In addition, many hiring processes focus on requirements that only a small portion of the Brazilian population could meet, and which are a hindrance to the majority.

Such discrepancies are seen on a daily basis in the requirements listed in job ads, such as fluency in a second language. Sure, some people are able to study on their own and become fluent in the much-requested language that, more often than not, is never put into practice during work. Some black people end up having to choose between working to survive or paying for a foreign language course and dedicating hours on end to mastering the second language.

In these situations, who gets hired through such processes? A black, favela resident, who has always struggled to survive and still managed to learn the foreign language? Or someone who had all the necessary resources and went on a super student exchange program to the U.S. or to a European country and had the opportunity to speak to natives and come back home fluent in the language?

The love lives of black women are also affected by white privilege. Simone Santos,* a 41-year-old black woman from São Paulo, reports never having had a serious boyfriend or husband, even though she had a child with a man who never committed to her:

“We stayed together for a while, but he never introduced me to his family, even though I got pregnant. Today, I know he’s married to a blonde who has children by other men. I keep thinking to myself: all the white women I know, even if they’re not as pretty or have a life as comfortable as mine, are always in a relationship. Meanwhile, I’m alone, despite hearing from friends that I’m pretty and smart.”

Santos’ reality is analogous to that of many black women in Brazil. Among the books that address this theme, The Solitude of the Black Woman: Her Subjectivity and Desertion by Black Men in the City of São Paulo, an outgrowth of Claudete Souza’s dissertation, is a breakthrough in pointing out the disadvantage of black women compared to white women when a black man chooses a partner for love. Izabel Accioly explains:

“The ideology of whiteness convinces black people that their hair, nose, and skin tone are ugly. That beauty is being white with straight hair, light skin, and light eyes. Whiteness is an entire system of white supremacy.”

Can White People Support the Anti-Racist Struggle?

It is possible, however, to join the anti-racist struggle while being a white person. This is what Accioly had to say:

“White people need to understand that if they were raised in a country that has been structurally racist ever since the Portuguese invaded these lands, it was created and conditioned by racism. The first step is to understand that racism is part of the problem and to stop denying that it exists.”

Accioly lists anti-racist attitudes which can be taken by white people: “Hiring black people; looking deeper into context; being aware of one’s own privilege; educating one’s children to respect black people.” According to the anthropologist, if the white person is in a leadership position, it is important that they observe whether there are black people being hired and the scope of hiring mechanisms.

Therefore, it is not coherent to make a call for black job candidates asking for fluent English or experience as a foreign exchange student because, structurally speaking, there is an inbuilt deficit for people whose ancestors were enslaved during the country’s recent history. This is not coherent, especially considering that black people still have less material power and less access to education than white people. In a country where only 5% of people speak English and only 1% speak it fluently, how many within this select few could possibly be black?

The gulf in Brazil is so wide that, according to the report Social Inequalities by Color or Race in Brazil, released in 2019 by IBGE, white people represent 70% of the wealthier population, while blacks make up 75% of the poorest. This in a country that’s 54% black.

Finally, according to Accioly, white privilege is sort of an undue advantage that every white person has, even if they don’t want to enjoy it. Situations experienced by black people every day, such as being followed around inside a supermarket and being accused of not paying for a product, are not routinely experienced by white people, who are not perceived as threats. It is a privilege of whiteness to go to the market, do your shopping and return home alive. An example is the case of João Alberto, killed by security guards at the Carrefour supermarket, in Porto Alegre, and so many others whose names we’ve never even gotten to know. Even if those benefited by whiteness do not like to hear it, it is still important to say: black lives matter!

*Simone Santos is a pseudonym, chosen to preserve the source’s identity, who prefers not to be identified.

Listen to the Accompanying Podcast in Portuguese Here:

About the author: Camila Fiuza is a a journalist, graduate of the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), and the product of public schools. She is a member of the Northeastern chapter of the Mothers of May. A black, peripheral woman who fights for human rights and against racism, Fiuza has contributed to community radios and worked for Record TV Itapuã and Band News FM Radio, in Salvador.

About the artist: Natalia de Souza Flores was born and raised in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone and is a member of Brabas Crew. With a degree in Graphic Design from Unigranrio in 2017, she has worked as a designer since 2015. She launched a magazine of collective comics called ‘Tá no Gibi’ in 2017 at the Rio Book Biennial. Her main themes are based in African culture, using cyberpunk, wicca and indigenous elements.

This article is the latest contribution to our award-winning reporting project, Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.