This is the second in a series of four articles about the “Degradation of the Pantanal Carioca,” as Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone wetlands were once known.

On June 21, helicopter images captured the water hyacinth proliferation in the Chico Mendes Park in Recreio dos Bandeirantes, in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone. The vegetation had taken up almost 50% of the water surface of the small lagoon Lagoinha das Taxas. This process has increasingly compromised drainage and encouraged flooding in the region, as well as contributing to mosquito outbreaks. The massive water hyacinth blooms are a consequence of eutrophication—a pollution process where rivers and lakes acquire a cloudy color and extremely low oxygen levels. This causes the death of numerous animal and plant species and greatly impacts water ecosystems. The presence of cyanobacteria toxins in the region’s lakes has been noted by researchers since the 1980s.

Cyanobacteria toxins are harmful to animals and can cause intoxication in humans. Since the system of lagoons around this area of Rio de Janeiro, called Jacarepaguá, is linked to the sea, the presence of toxic cyanobacteria can result in public health problems along the coastal region’s recreational beaches, such as Quebra-Mar. As a result, in early 2007, fishing and the sale of fish from the Jacarepaguá lagoons was banned. At the time, analyses of fish revealed contamination, while the fishermen—generally from communities bordering the lagoon system—received a minimum wage to help sustain their families.

For Sérgio Ricardo—ecologist, environmental manager and member of the Living Bay Movement—the lack of public housing policy is linked to the lack of basic sanitation. And the biggest consequence of this state neglect and the heavy influence of real estate development in the region is pollution of its bodies of water.

“There is no sanitation! All of the region’s rivers and bodies of water, just like those in the Baixada Fluminense, Rio proper and the East Metropolitan Region, have turned into ditches; a civilizational tragedy. Which is a shame, because we are losing out on tourism, on leisure. The lack of sanitation increases the cost of public health services through the spread of waterborne diseases. From an outsider’s point of view, the stupidity of this lagoon contamination is ugly. For those on the inside, it’s even worse. Hundreds of sofas, tires, cars and untreated sewage from the past. A large sanitation works project began construction in the 1990s, a station was built in Barra and such, but the whole issue is that investment in sanitation isn’t kept up. Since the 1970s, when the country’s metropolitan regions grew, we did not create a housing policy, and without housing policy there will be no sanitation. One is closely linked to the other.” — Sérgio Ricardo, Living Bay Movement

In September 2021, the third barqueata calling for environmental sanitation of the Jacarepaguá lagoons was held—a nautical protest demanding a clean-up of the lagoons in the complex. Participants included fishermen from the Anil Channel and the favela of Rio das Pedras, as well as the Living Bay Movement.

Outraged by the six tons of dead fish found on the region’s beaches, the fishermen held another protest in March 2022, six months later. This time, they occupied Abelardo Bueno Avenue in the elite West Zone neighborhood of Barra da Tijuca.

Francisco Alberto dos Santos—member of the Anil Channel Fishermen Association—is one of the region’s most experienced fishermen. He compares how many kilograms he used to fish daily from the lagoon system in the 1970s and 1980s, with how many he fishes now.

“We ended up ‘making a tide’ to fish a yield of 600kg per boat per day, every little kayak. I, myself, with two boats, frequently brought in 1,200kg. Today you go to one of these lagoons and can’t fish anything, because of the pollution… from 1976 to 1989, roughly, it was still providing good stocks. In other words, over time these things have become much more difficult… if (the fisherman) goes fishing today, he brings in 50kg, 30kg. This means he can barely survive. Understand?”— Francisco Alberto dos Santos, Anil Channel Fishermen Association

In May 2022, a public hearing was held in Barra da Tijuca’s People’s Chamber to discuss the remediation of the Jacarepaguá lagoon system. State Deputies that take part in the Environmental Defense Commission and Environmental Sanitation Commission within the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ), representatives from the State Environmental Institute (INEA), municipal water entity Rio Águas and the Public Prosecutors’ Office held debates regarding the millions of liters of untreated sewage disposed from the Recreio dos Bandeirantes, Vargem Grande and Vargem Pequena neighborhoods into the region’s lagoons.

In an interview for the program Balanço Geral, on TV Record, Prosecutor José Alexandre Maximino said there are at least 400 illicit sewage disposal points in the drainage network.

Adacto Ottoni—PhD in Public Health and professor at the Rio de Janeiro State University’s Sanitation and Environmental Engineering Department (DESMA/FEN/UERJ)—explains that pollution degrades water quality and causes silting in the lagoons and rivers, in turn causing floods and inundations in rainy periods:

“As well as degrading the water quality, pollution causes silting in the lagoons and rivers. And then what happens in rainy seasons?! I say this every year, places receiving rainfall are screwed, because the water has no way of draining, everywhere is silted. The problem is very severe and has a solution. What is missing is political will and accountability from our public agencies, from our mayors and governors, to enable a solution to the problem.”

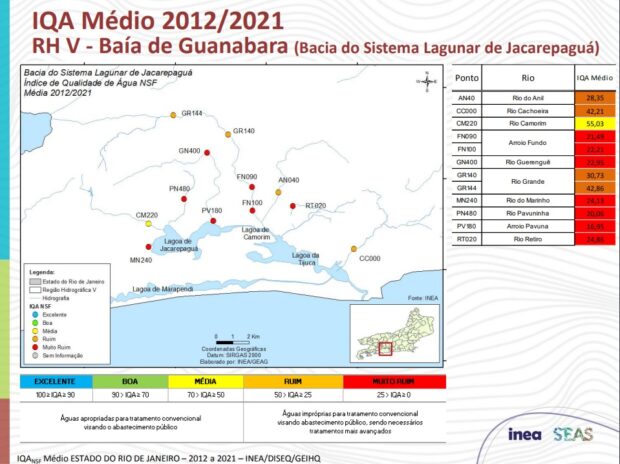

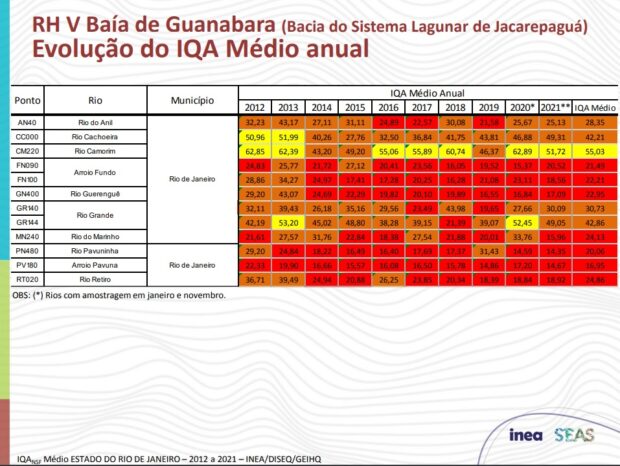

According to the Systematic Monitoring of Rivers in Rio de Janeiro State, carried out by the State Institute for the Environment (INEA) and the Environment and Sustainability State Secretariat (SEAS), between 2012 and 2021, the average water quality index of the Jacarepaguá lagoon system’s basin classified five rivers as ‘very bad’, six as ‘bad’ and one as ‘average’. The one classified as ‘average’ has suitable water for conventional treatment, while the bad and and very bad do not, requiring more advanced treatment.

According to the Systematic Monitoring of Rivers in Rio de Janeiro State, carried out by the State Institute for the Environment (INEA) and the Environment and Sustainability State Secretariat (SEAS), between 2012 and 2021, the average water quality index of the Jacarepaguá lagoon system’s basin classified five rivers as ‘very bad’, six as ‘bad’ and one as ‘average’. The one classified as ‘average’ has suitable water for conventional treatment, while the bad and and very bad do not, requiring more advanced treatment.

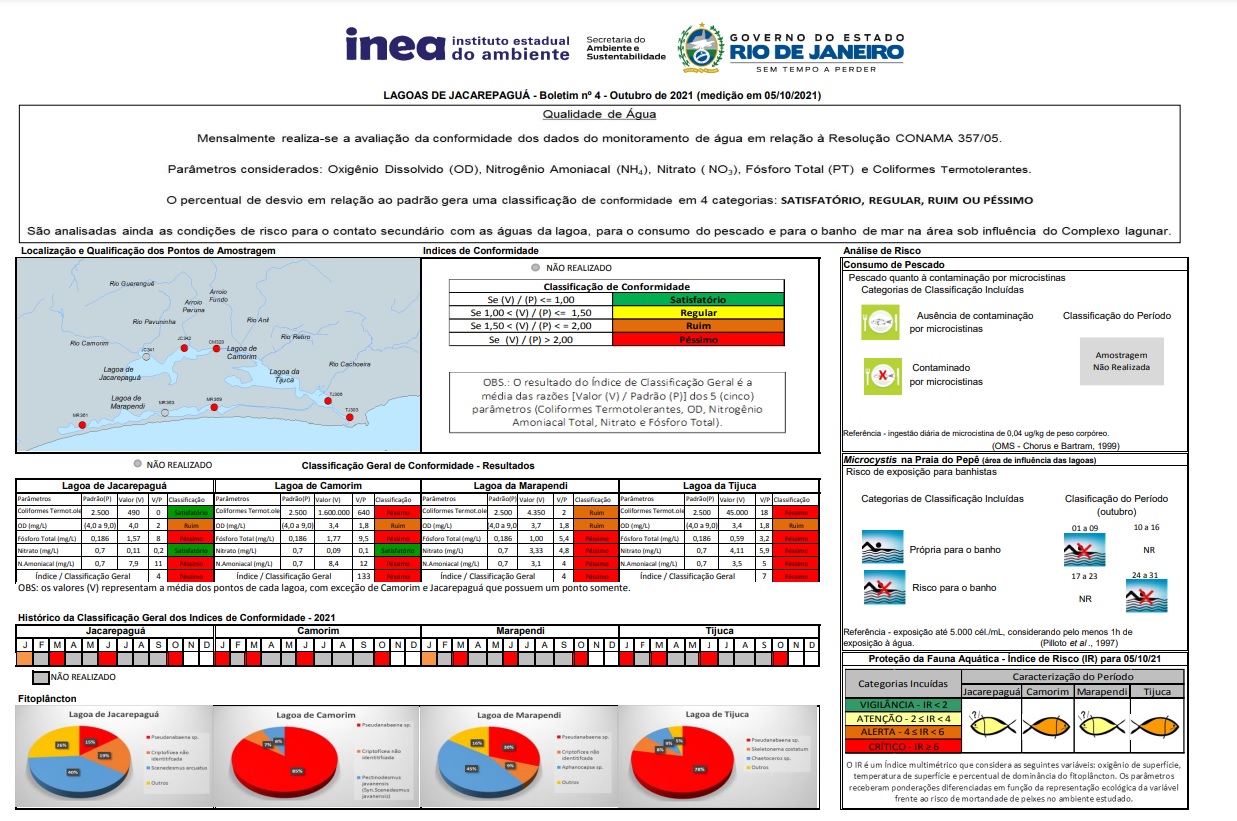

In their latest report, INEA and SEAS also classified the system’s four lagoons as ‘terrible’, and a risk to bathers. They are in a state of ‘alert’ and ‘attention’ with regard to aquatic fauna. According to sampling results, the Tijuca and Camorim lagoons are more polluted than the Marapendi and Jacarepaguá lagoons.

Comparing the sample data to the legislation’s established standards, the four lagoons that form the Jacarepaguá Lagoon Complex are not conforming to the values of the CONAMA nº357/2005 Resolution. There is also a lack of regulation in the systemization and sharing of information about water quality in the lagoon complex. Up to the writing of this article, the last data collection was in October 2021. Adacto Ottoni questions the regularity of monitoring collections by the INEA in the Jacarepaguá Lagoon Complex.

Comparing the sample data to the legislation’s established standards, the four lagoons that form the Jacarepaguá Lagoon Complex are not conforming to the values of the CONAMA nº357/2005 Resolution. There is also a lack of regulation in the systemization and sharing of information about water quality in the lagoon complex. Up to the writing of this article, the last data collection was in October 2021. Adacto Ottoni questions the regularity of monitoring collections by the INEA in the Jacarepaguá Lagoon Complex.

“For those of us that work with the environment, monitoring equates to medical examinations requested by a doctor for their patient. A river is a living organism and to understand its health, you need to monitor it. Unfortunately, does monitoring exist? Yes, but is there a guarantee that INEA collects the samples at low tide? I do not have this guarantee. Sampling in higher tides has no sanitary significance, as the sea water enters and dilutes the sewage, causing a lower result.”

By email, INEA informed that it monitors the eight points of the Tijuca and Jacarepaguá lagoons bimonthly, and the rivers that flow into the lagoon system quarterly, and publishes results on the organization’s website. The institute also said it monitors the effluents through the consumer protection Procon Água program and checks deforestation alerts issued by the Olho Verde program that monitors deforestation of the Atlantic Forest in Rio via satellites.

Regarding urban planning concerns, Rio’s Urban Planning Municipal Secretariat (SMPU), via the Macroplanning Administration, said that housing objectives, guidelines and actions are established by the city’s Sustainable Urban Development Master Plan. An example of this is the Social Interest Housing programs (HIS) in Zones of Special Social Interest (AEIS), that lay out an upgrading plan, as well as informing on the conditions for upgrading in favelas and irregular lots, and resettlement conditions for low income populations in at-risk areas.

The SMPU further informs that, in 2021, the Complementary Law Project Nº44/2021 was sent to City Council. It addresses urban and environmental policies of the locality, imposing the revision of the Rio de Janeiro Master Plan. Ultimately, the SMPU highlights that the application of sectoral policies depends on availability of resources, according to the budgets of implementing organs approved in legal annual budget guidelines.

This is the second in a series of four articles about the “Degradation of the Pantanal Carioca,” as Baixada de Jacarepaguá, in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, was once known.

About the Authors:

Felipe Migliani has a degree in journalism from Unicarioca with a focus on Investigative Journalism. Working as an independent journalist and freelance reporter at Meia Hora and Estadão newspapers, he collaborates with the Coletivo Engenhos de Histórias, which investigates and recovers history and memories from the Grande Méier region, and with PerifaConnection.

Fernanda Calé has a degree in journalism from Unicarioca with a focus on Popular Communication as a way of reaching a diverse public in a clear and simple manner. Two years ago, she helped found Agência Lume—a communication agency producing independent journalism in Jacarepaguá, focusing on Rio das Pedras, where she was born.