Clique aqui para Português

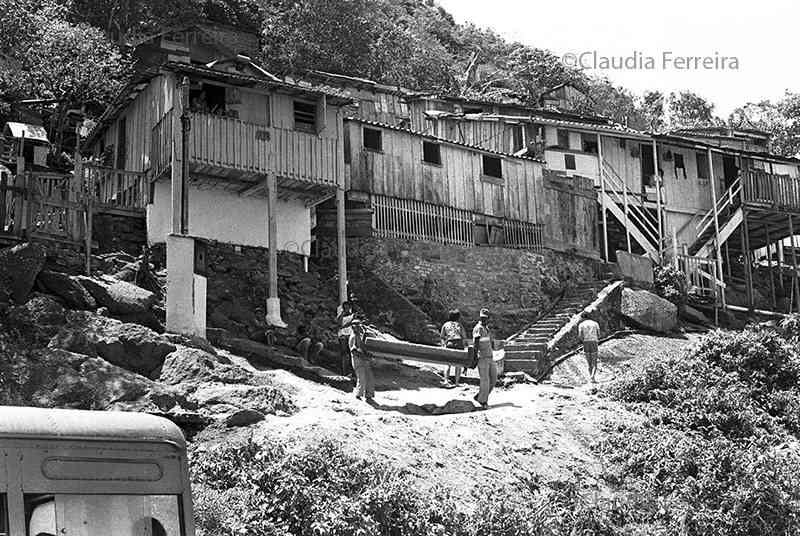

Over 175,000 people were evicted from favelas in the state of Rio between 1960 and 1973, a period historian Mário Brum calls the “Era of Evictions” in his thesis Cidade Alta: History, Memories and Favela Stigma in a Public Housing Complex in Rio de Janeiro. The favela of Vidigal remained, however, despite 45 years ago, on October 24, 1977, residents waking to markings on their doors of “FL” (Fundação Leão XIII) along with a number.

This was how Fundação Leão XIII marked houses slated for removal in the community’s micro area known as 314. Plans stated that occupants would be transferred to Antares, in the city’s extreme West Zone, on trucks belonging to the waste management utility, Comlurb. Human beings treated like garbage!

The Vidigal Residents’ Association (AMVV), with support from congressman Aluísio Teixeira, secured the suspension of forced evictions that day. Even so, some residents wanted to leave. They believed in the promise of a duplex apartment for each family. A group of women went to Antares to check whether the location offered by Mayor Marcos Tamoyo (“Marcos Tramoia,” or “Marcos the scammer” in a loose translation, was his nickname in Vidigal) had sufficiently sound structural conditions to replace the area in which they lived and socialized together. The replacement homes were miniscule. There was no school, daycare, hospital. Nothing. According to one of the leaders at the time, Carlos Duque, “Antares looked like a concentration camp.”

Congressmen Délio dos Santos and Flores da Cunha joined the residents’ struggle. Sobral Pinto, the celebrated lawyer known as “Mr. Justice,” took on the cause of the favela and assigned his representative, Bento Rubião, as defender of the residents threatened by forced evictions.

Community leaders—Seu Armando, Carlos Duque, Carlinhos Pernambuco, Mário Sérgio, and Paulo Muniz, or Paulinho—came up with a number of strategies to delay the removals. Breakfast was offered to Comlurb employees in exchange for them taking just a broom, a bucket, or other objects of lesser importance from the homes during each trip. Organized by school principal Eneida Veloso Brasil, students from the Almirante Tamandaré Municipal School formed a human chain to prevent the trucks from reaching residents they were attempting to evict. Even the carnival parade by samba school Acadêmicos do Vidigal was used as an argument to postpone the eviction orders. After all, carnival is Brazil’s largest popular festival and samba is rooted in the favelas.

Residents continued coming up with resistance strategies. Meanwhile, powers of attorney were issued, allowing each eviction attempt to be blocked by Bento Rubião. Residents who doubted his abilities or the effectiveness of the document were, unfortunately, taken to Antares, since they lacked legal representation.

One resident had recently experienced a breakup and took advantage of the opportunity to start a new life elsewhere: he agreed to go to Antares, an episode portrayed in the film Bandeira de Retalhos [Flag of Scraps], by Sérgio Ricardo. This man’s shack became the headquarters of the residents’ association.

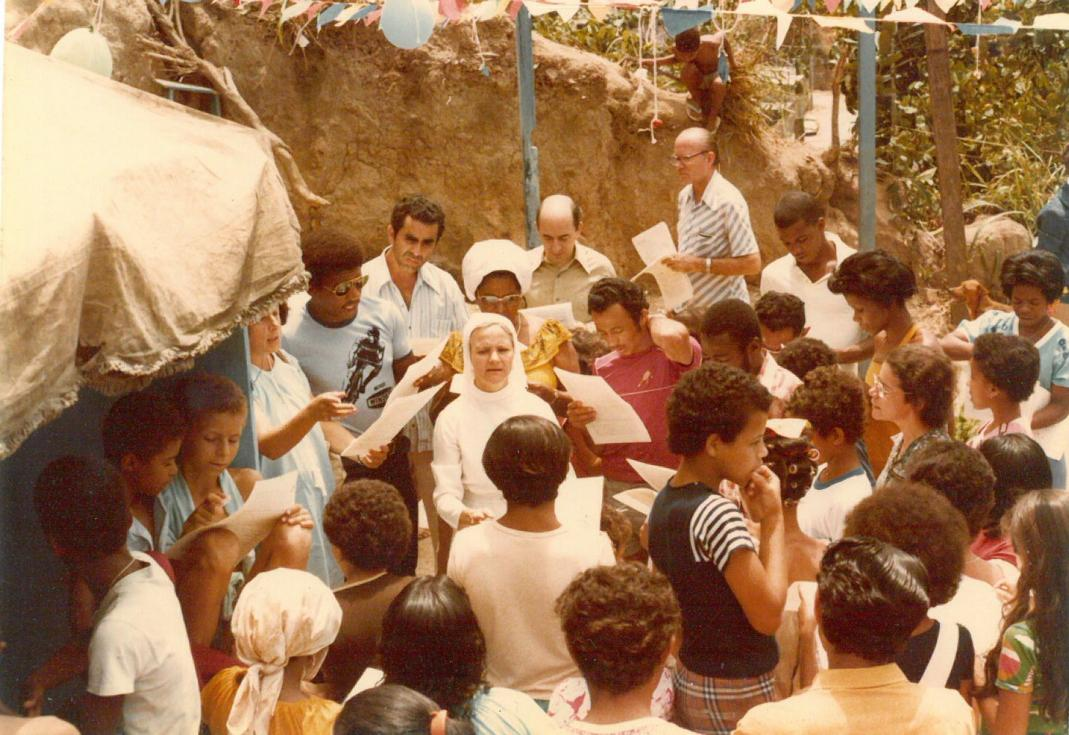

Vidigal was also supported by members of the Catholic Church aligned with liberation theology. Archbishop Dom Eugênio Sales himself was an avid supporter of various favela causes. Residents had no ties to a specific political party, but instead were individuals who belonged to the oppressed class that had organized in the quest for the right to housing. Because of this fight by Vidigal’s favela population, the Favelas Pastoral Committee was founded in 1977. Thanks to this body of the Catholic Church, Vidigal won support from the renowned lawyer mentioned earlier, Sobral Pinto.

The argument to justify removal of residents was the risk of landslides on the hill. A geologist from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) was hired by the Favelas Pastoral Committee, whose evaluation showed that the area was not at risk of collapsing. It was found that the true motivation was real estate speculation: they planned to build luxury housing for the dominant class.

Popular resistance to removing favela homes located between the two South Zone neighborhoods of São Conrado and Leblon, at the height of the military dictatorship, caught the press’s attention at the time. People from outside the favela volunteered to help with local development. University students, doctors, lawyers, architects, and journalists offered to assist Vidigal’s population.

The fight won the support of singer Ney Matogrosso, for example, who performed at the Stella Maris School to help cover the legal costs of defending residents against evictions. According to Filomena Di Prínzio, member of the AMVV women’s group and contributor to the newspaper O Mensageiro, an important local media outlet, the singer’s performance with bananas covering his private parts was a little shocking given the nuns in attendance from the private Catholic school that had granted the space.

The AMVV was strong, respected, and active. In fact, it helped structure and establish various other favelas’ residents’ associations, and was founded in 1967 to push back on eviction measures (the threats of removals didn’t begin in 1967, although they were more intense that year). José Ferreira was the first president of the AMVV. Modesto, the vice-president, was a babalorixá [Candomblé priest] who had a terreiro [place of worship] at a spot known today as Rampa do 314. As the institution representing the favela population had no headquarters, community meetings were held at Father Modesto’s Candomblé terreiro. Many of these individuals were Catholic, but their religious beliefs were unimportant: the goal was establishing unity for the sake of organizing the favela and its resistance movement. Faith didn’t get mixed up with collective interests.

In the 1970s, José Ferreira and Father Modesto moved away from Vidigal. Community leadership met at corner stores Birosca da Conceição and Birosca do Aluísio. In the 1980s, the current AMVV headquarters was built through collective efforts.

Vidigal went on winning its legal battles, but the fight only ended in 1980, the year Pope John Paul II came to visit. The highest representative of the Catholic Church chose this favela as one of his stops during his trip through Brazil due to the repercussions arising from the resistance by the favela’s population and the relationships of its leaders with the Favelas Pastoral Committee. On the eve of his visit, then-Governor Chagas Freitas signed the expropriation decree of Vidigal for social purposes. Vidigal had won. Some attribute this victory to the pope’s visit. However, if the favela’s cause generated such a great degree of attention, it was because there was unity and resistance by residents, led by the institution representing them.

According to Paulinho, the pope’s visit guaranteed residents the right to stay. After all, it made headlines around the world. No one dared evict anyone from the “Pope’s favela,” as it became known. During his visit, His Holiness surprised everyone by donating his ring to Vidigal. Today, the treasure is guarded at the Archdiocese of Rio de Janeiro’s Religious Arts Museum. A replica is kept at the Saint Francis of Assisi Chapel in the community and is put on display during church festivities.

The current headquarters of the AMVV, as well as other public buildings—such as the health clinic, the cultural center, the Saint Francis of Assisi Chapel—were built through collective efforts. On weekends, residents paved the roads and installed water pipes. Men, women, and children joined forces in the midst of mud, cement, and bricks. The houses were also built this way: collectively. Including, by the way, my family’s own home.

The unity of residents and their fighting spirit in the face of adversity allowed them to achieve all they did over the years. In particular, the Youth Group and the AMVV Women’s Group merit special mention. The first was responsible for community events, and the second for submitting requests for infrastructure improvements in Vidigal to the authorities and following up on them, such as water supply, street lighting, and building of daycare centers and clinics.

Vidigal has a unique way of naming its streets. Among the measures adopted by these groups organizing the favela was the decision to name the streets after those who were involved in the fight against eviction. Lawyers, journalists, people with ties to the Catholic Church (the Favelas Pastoral Committee), community leaders (many mentioned here), and dates of note in the favela’s history (including October 24) are paid tribute. The favela determined its own fate.

In terms of nomenclature, there’s another unique point about Vidigal: a beach is named after it. In 1968, construction work for the Sheraton Hotel in front of the community had begun, which planned to give its guests exclusive access to the beach. Residents protested. In 1971, we legally won the right to freely access Vidigal Beach.

Another milestone in Vidigal’s history was the Brick by Brick concert hosted in 1962 at the State University of Rio de Janeiro’s (UERJ) Concha Acústica, created and directed by Sérgio Ricardo. The film director and composer was a resident of Vidigal, one of the articulators of the strategy to resist removals, and served as cultural director of AMVV. He produced the 1962 show to raise funds to build brick-and-mortar houses to replace residents’ shacks, in addition to rebuilding homes for families affected by that summer’s heavy rains. The performance included the participation of renowned artists such as Zé Ketti, Zezé Motta, Gonzaguinha, João Bosco, Chico Buarque, and others.

Another edition of the concert was put on collectively in 2016 by local leaders and artists. Directed by its creator, Sérgio Ricardo, the event aimed to revisit and celebrate important moments in the 75 (official) years of Vidigal’s history, celebrated in 2015 (due to inopportune weather, the show was held the following year). We enjoyed performances by legendary musicians that had participated in the first edition, including João Bosco and Chico Buarque, in addition to the Portuguese artist Carminho and various artists from Vidigal itself.

Our cultural talents are undeniable! In the 1980s, samba circles were organized by Marcão, Marquinho, Vidigal Samba Show, and other local residents, attracting top artists to the favela. This was the case with the first lady of samba, Jovelina Pérola Negra, who paid tribute to the favela with the samba Catatau.

Further generations of samba artists emerged in Vidigal, such as Fundo de Varanda. Absorbing influences from the well-known group from Rio de Janeiro, Fundo de Quintal, young residents presented “grown-up” samba to the favela’s residents. Since then, a number of musical talents have emerged, including Melanina Carioca, Só Jesus Salva, A Bronca, BatucaVidi, Thiago Martins, and Nifre Records.

It’s worth highlighting that one of the main theater groups and incubator for modern cinema actors, Nós do Morro (Us from the Hill), was established in Vidigal. Founded in 1986, the group took shape based on Guti Fraga’s dream of providing residents access to art and culture. Over its 36 years of uninterrupted activities, Nós do Morro has earned national and international acclaim. It has benefited 12,000 people and put on 103 plays, created 10 short films, 20 professional performances, and reached a combined audience of 50,376 people. It’s a symbol of resistance through art! This year, actors Babu Santana and Marcello Melo took charge as directors. The management team consisting of children who passed through the institution embodies the spirit of renewal, showing that the roots have taken hold and the tree is fruitful. Many seeds will sprout.

Speaking of the favela’s roots, Acadêmicos do Vidigal, an old samba group founded in March 1976 and today a samba school, is one of the greatest representatives of our culture and spirit of resistance. Even without a space for rehearsals and no budget for costumes, they bring carnival to the streets every year. These are generations committed to elevating the Vidigal samba school to the position of prominence it reached in the 1990s.

Resilience is one of Vidigal’s trademarks. After landslides in the area known as Forte, the City evicted residents from their homes. The area of approximately 8,500m2 became a place for dumping anything that was no longer of interest. Furniture, tires, appliances, and every type of garbage was abandoned there. A group of residents including a community street cleaner removed 16 tons of waste and debris, transforming it into the Sitiê Ecological Park. What once was a garbage dump today is recognized as an agroforest by Rio de Janeiro’s Environmental Secretariat, for preserving native forest and cultivating the soil.

A formidable opponent, Vidigal also makes its presence known in the fighting ring. The Instituto Todos na Luta (All in the Fight Institute) is geared towards boxing training and two of its athletes represented Brazil in the 2016 Rio Olympics: Michel Borges and Patrick Lourenço. In 2012, Esquiva Falcão was a medalist at the London Olympics. Founded in the 1990s by boxing teacher Raff Giglio, the project has won 37 medals: 12 gold, 8 silver, and 17 bronze.

Evidently, the history of Vidigal is not one marked exclusively by victories. Like every favela, our trajectory winds through efforts to expel us: attempts at forced evictions, disputes from rival groups to dominate the traffic of illicit substances, landslides, police brutality, and gentrification.

Still today, residents receive eviction notices. On February 6, 2019, Alerta Rio, the city’s weather alert system, recorded 12 millimeters of rain and winds of over 100km/hr in Vidigal. These phenomena caused a small landslide, toppled many houses, and took one life. In the dark and with no power, the favela joined forces to help the victims. It was chaotic. Currently, 30 families from the area known as Jaqueira receive a pittance of R$400 (US$80) as social rent to survive in an area which, due to gentrification, has no housing available for this amount. Other residents don’t even receive this allowance.

Last August, 63 families from the area were informed that their homes would be demolished. The compensation offered by the Municipal Housing Secretariat is on average R$60,000 (US$12,000). One house was valued at R$11,942.69 (US$2323,16). It goes without saying that this amount is insufficient to ensure this family can remain in Vidigal or move somewhere else that is livable.

Clearly, Vidigal still has challenges ahead. The labels that outsiders give to the place (such as Fancy Favela, Pop Favela), the breathtaking views, and the gentrification end up camouflaging problems specific to peripheral territories. Meanwhile, residents plan resistance strategies through art, education, culture, sports, and political awareness.

45 years ago, Vidigal engaged in resistance despite a full-on military dictatorship. Despite the still-current president of the country dismissing favelas as criminal territories, Vidigal is in fact a force to be reckoned with, with citizens who typically elect candidates committed to the working class. Resistance is our trademark and democracy is our flag. We won’t back down from this position. We must preserve and disseminate this history so that the present can be equipped with tools for designing the future. The fight must go on!

About the author: Bárbara Nascimento was born and raised in Vidigal. A Portuguese teacher in the Rio de Janeiro city and state public school systems, she holds an undergraduate degree in Modern Languages (UFRJ: 2002) and a Master’s in Social Memory (UNIRIO: 2019). She founded and directs the Vidigal Nucleus of Memories, a range of initiatives that prepares archives and keeps records that aim to support the formation of a collective memory in Vidigal.