This is the third in a series of four articles about the “Degradation of the Pantanal Carioca,” as Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone wetlands were once known.

Rio de Janeiro’s Climate Change Adaptation Strategy was launched in 2016 through the Rio de Janeiro city government’s partnership with the Center for Integrated Studies on Climate Change and the Environment (Centro Clima) and the Alberto Luiz Coimbra Institute for Graduate Studies and Research in Engineering at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (COPPE-UFRJ). The document indicates that the city’s Planning Area 4’s (AP4) drivers of growth are threatening the Pedra Branca massif and the Jacarepaguá Lagoon Complex—potentially impacting people, properties and natural ecosystems.

On page 38, under the category “Urban Planning and Housing,” the document reveals that “The loss of forests could exacerbate floods and high temperatures. An increased average sea level could threaten the urbanized coastal regions of the Barra da Tijuca Administrative Region (AR), as well as possible flooding around the whole Lagoon Complex.”

The document also predicts impacts to the “Urban Mobility,” “Health,” and “Strategic Infrastructure” categories. With respect to mobility, it states that the increased average sea level could threaten the integrity of cycle paths and pavements, harming active transportation and increasing car and bus use. This could happen especially in the Jacarepaguá and City of God Administrative Regions (RA) due to floods and landslides on the slopes and hills of the Pedra Branca and Tijuca massifs—some of which could potentially reach important public roads.

In the health category, the study indicates that the Jacarepaguá RA presents the greatest vulnerability to disease, especially leptospirosis and visceral leishmaniasis, while the City of God RA presents low socioeconomic indicators. Extreme climatic events can exacerbate these problems. And in the infrastructure category, the study highlights the growing exposure to high temperatures and mass of landslides.

On page 40, the study reveals how this situation occurs in the Jacarepaguá lagoons:

“In instances of more intense and frequent rains, the flow of rivers that drain into the lowlands through forest massifs will be intensified, contributing to a greater input of sediments and pollutants into the lagoons. Higher temperatures over consecutive days, coupled with dry periods, contribute to a reduced environmental quality of the lagoons and the rivers and channels of the respective drainage basins. Waves and undertows, if very strong, are capable of altering, even if temporarily, the hydrodynamics of the lagoons—causing sediment stirring at the bottom and flooding surrounding lowland areas. With sufficient duration to allow the slow inflow of water into the Jacarepaguá Lagoon Complex, the weather tides—originated from extratropical cyclones with the strength of a hurricane—will advance the flooding of adjacent lowland areas and the elevation of the water table, which could also have altered salt content. An increased water surface could block the flow of channels and rivers, causing floods which may be enhanced by strong rains and the syzygy high tides.”

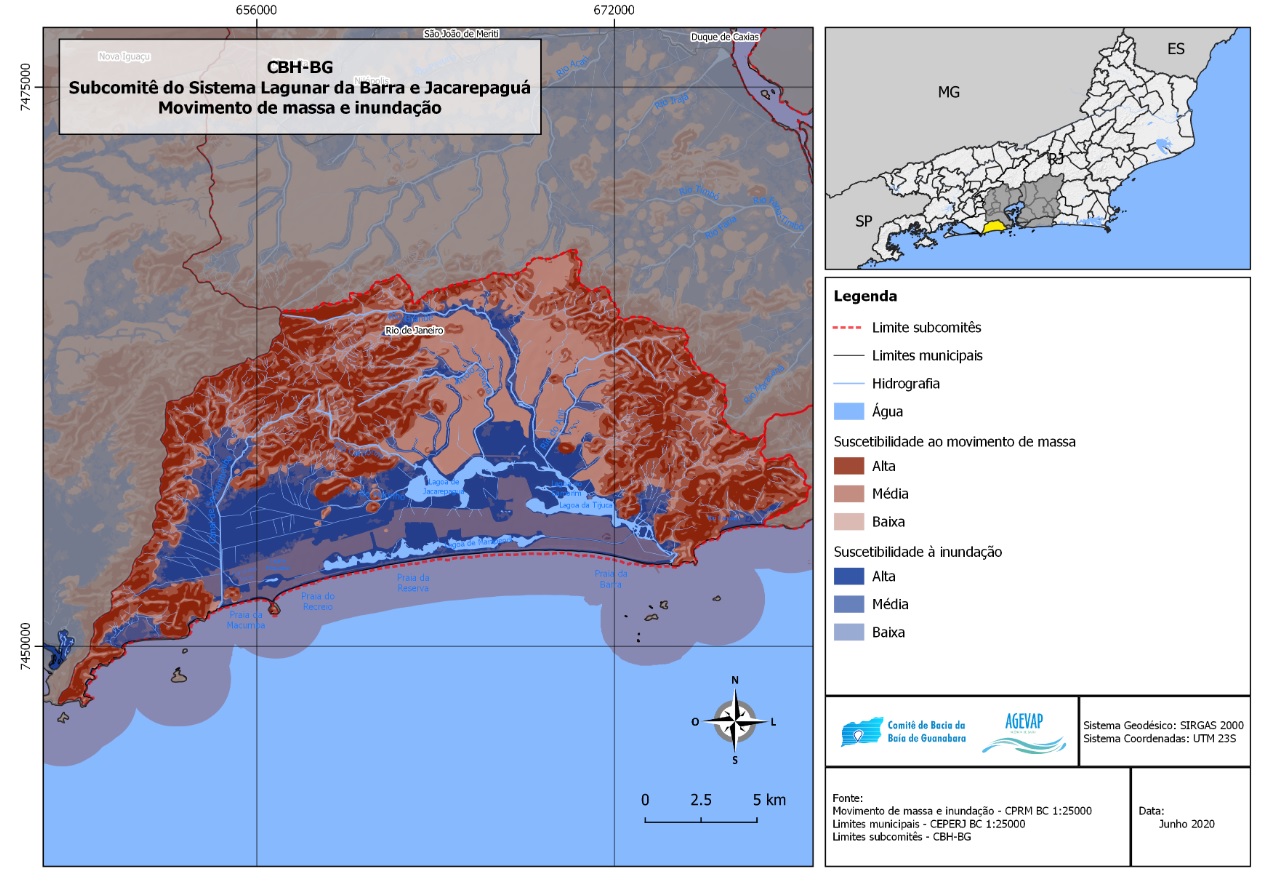

The Guanabara Bay Basin Committee and the Maricá and Jacarepaguá Lagoon Systems (CBH-BG) have numerous maps that are available for download. The “Mass Movement and Flooding” map shows that a large part of the AP4 is highly susceptible to mass movement and flooding, being one of the areas most threatened by climate change in Rio de Janeiro. If this happens in the future, places such as the favela of Rio das Pedras, for example, may disappear from the map.

Flooding is increasingly common in the Rio das Pedras favela. Located between Barra da Tijuca and Jacarepaguá, Rio das Pedras emerged in the 1950s and its growth and occupation process was accelerated by the migration movement occurring across Rio de Janeiro at the time. Migrants from numerous regions in the country came to live in Rio das Pedras—the largest number from the Brazilian Northeast. Barra da Tijuca experienced increased employment opportunities with this migration to Rio de Janeiro. The swampy area that became Rio das Pedras, which also covered many sandbanks, was occupied by residents with no help from the state or municipal governments. According to the last census by the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE), carried out in 2010, Rio das Pedras has 63,000 residents—one of the most populous favelas in Rio.

The favela is named after the river that cuts through the region. It is silted and is currently undergoing a cleaning and dredging process, which is still in its initial stage. From the region that comprises Engenheiro Souza Filho Avenue up to the sandbanks, the water body is still completely silted. The cleaning process is predicted to end in March 2023. While the cleaning is not complete, floods are increasingly common and disrupt the day-to-day lives of residents and local merchants.

Douglas Teixeira, 27, is a resident of Rio das Pedras and reports the problems experienced by residents and local merchants caused by floods:

“As well as fear of the rain, we now also have to worry about the tide movements impacting our lives, our schedules and even whether or not we can leave the house. I have lived in the Areinha region for at least six years, and this situation has been occurring with greater intensity since last year. Normally, there were two flood ‘seasons’: during heavy rains (in the summer) and high tides (at the end of fall and start of winter). Today, the tides influence our lives all year round, regardless of the weather.”

Adão Castro—Geography PhD student at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and member of the research groups River Dynamics and Management (Geomorphos/UFRJ) and Center for Hydrogeography Studies and Research (NEPH-UFF)—explains the impacts of urbanization on the Rio das Pedras river basin, and emphasizes that the flooding problem in the region is chronic and needs to be resolved by the public authorities:

“Before the occupation, this area was a continuation of the lagoon, with vegetation predominantly composed of cattails that occupied the swampy areas. Tide dynamics—the inflow and outflow of water through the Tijuca Lagoon—have always been present in this region. An urban drainage construction is necessary, starting with a sewage system construction, so that the sewage is collected and treated before it enters the lagoon.”

Launched in March 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report warns that the average increase in global temperatures could reach 3.5ºC if no practical measures for reducing greenhouse gas emissions are put in place on a global scale. With this, cities such as Rio de Janeiro can face increases of 3% in deaths caused by heat by 2050, and 8% by 2090. If these emissions are contained, this mortality rate falls to 2%. An increase in extreme rainfall is also predicted and, consequently, disasters such as floods and landslides.

The report also foresees fish production falling by up to 36% from 2050 to 2070, compared to 2030 to 2050. A catastrophic prognosis is established for the production of crustaceans and molluscs, nearing extinction with a fall of 97% in the same period.

“Fish mortality is primarily caused by eutrophication. It is political will [that impedes change]. [The solution comes from] the mayor’s decision, the governor’s decision. Through increased funding to the State Institute for the Environment (INEA), increased funding to the Environmental Secretariat for more inspectors, to have more vehicles, and to improve the laboratories, do you understand? This is not that much money. The cost of the fish mortality and degradation process is much greater. Is it worth a destroyed lagoon, a destroyed spring, a leak at the beach that will destroy tourism? So is this the better investment? Unfortunately, our politicians are not seeing this,” stated Adacto Ottoni—Public Health PhD and professor within the Sanitation Engineering and Environment department at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (DESMA/FEN/UFRJ).

In a statement, INEA informed of its installation of five eco barriers in the main rivers that flow into the region, aiming to stop trash from reaching the beaches—removing 3,352 tons of solid waste for proper environmental disposal in the first semester of 2022. The institute also informed that in the past two years, it carried out 54 surveys in gated communities and residential establishments in the region and adopted suitable legal measures when confronted with irregularities—such as fines and notices.

Through the Freedom of Information Act, the Municipal Environmental Secretariat (SMAC) responded saying that surveillance is undertaken based on complaints received through external channels, starting with an inspection survey in the location, interviewing residents and possible culprits. Following this, the final examination, aiming to prove the potential environmental harm, identification of who was responsible and damage remediation.

The SMAC informed that in the surveillance sector, there are currently seven technical professionals managing the AP4 surveillance, four technical professionals for the immediate examination of complaints and that, since 2021, the department has an Environmental Defense Coordination that reinforces the municipality’s environmental surveillance with hundreds of actions to fight deforestation and other environmental crimes. Finally, the SMAC emphasized that the State Government is responsible for the management of the Tijuca, Marapendi and Jacarepaguá lagoons, and that the city is responsible for the conservation of the Marapendi Environmental Protection Area (APA), including the revitalization of the Marapendi Channel.

This is the third in a series of four articles about the “Degradation of the Pantanal Carioca,” as Baixada de Jacarepaguá, in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, was once known.

About the Authors:

Felipe Migliani has a degree in journalism from Unicarioca with a focus on Investigative Journalism. Working as an independent journalist and freelance reporter at Meia Hora and Estadão newspapers, he collaborates with the Coletivo Engenhos de Histórias, which investigates and recovers history and memories from the Grande Méier region, and with PerifaConnection.

Fernanda Calé has a degree in journalism from Unicarioca with a focus on Popular Communication as a way of reaching a diverse public in a clear and simple manner. Two years ago, she helped found Agência Lume—a communication agency producing independent journalism in Jacarepaguá, focusing on Rio das Pedras, where she was born.