Published in Portuguese in November in celebration of Brazilian Black Awareness Month, this article features three black comedians who are dedicated to anti-racist comedy.

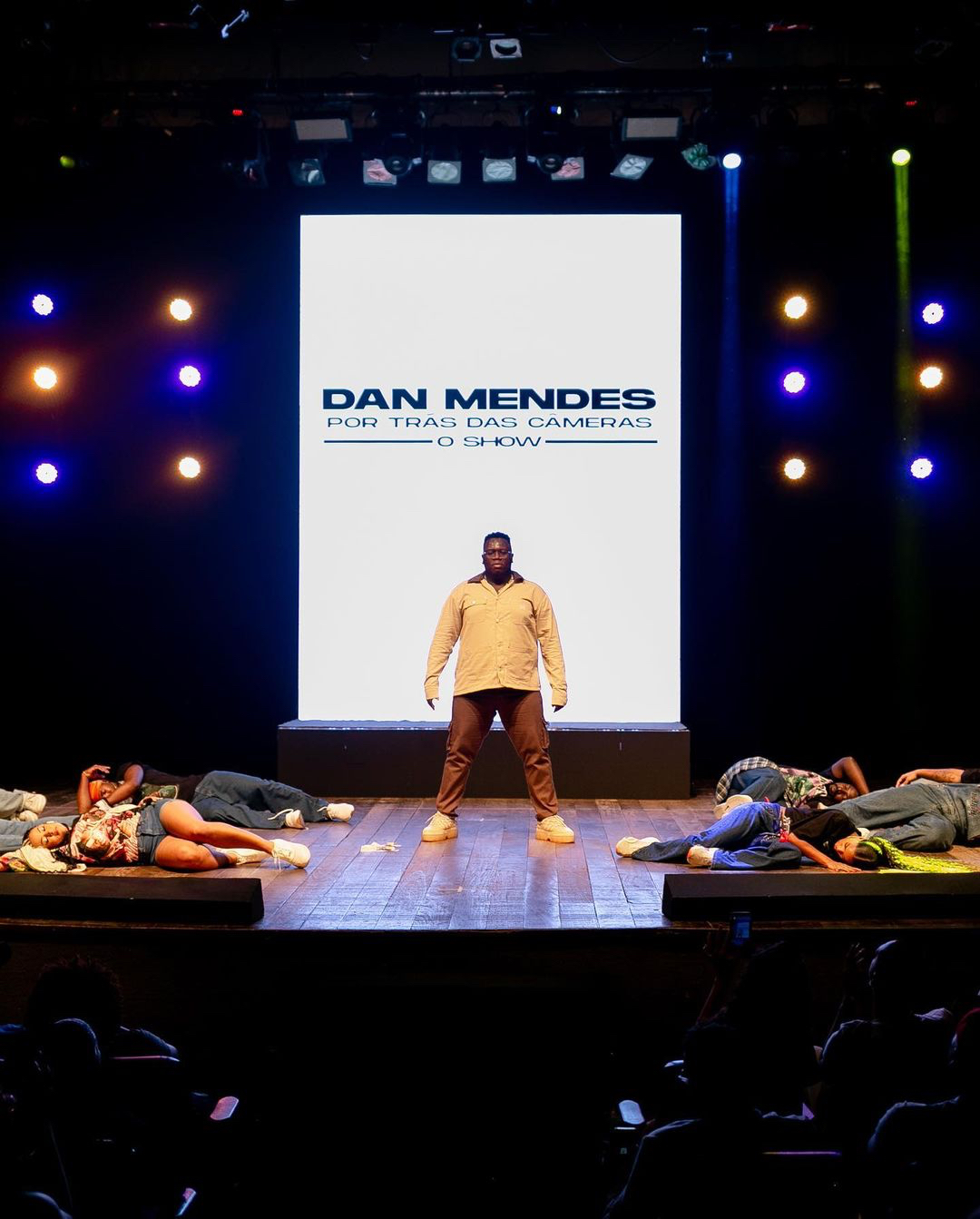

At the end of September, Dan Mendes—a black man who was born and raised in Greater Rio de Janeiro’s municipality of Duque de Caxias—premiered his comedic play Behind the Cameras – The Show in Rio’s North Zone. Tickets sold out in under 24 hours. He added a second day to the schedule and, again, the 455-seat theater was packed. The show mixes humor as a tool of anti-racist resistance alongside dance and theater, and received sponsorship from a beer company.

“I’m still absorbing everything that’s happened. [It’s a] very beautiful thing! Two sold-out shows in Rio de Janeiro. [They] sold out in 30 minutes. We wrote a new chapter in my story. Thank you,” Mendes posted on Instagram, where he has over 700,000 followers. On his social media, Mendes shares love advice and critiques society through humor. He has developed his comedies based on the experience of a black family that faces traffic, crowded buses, long journeys to work, difficulties acquiring basic consumer items, among other things that are so common for black families living in peripheral areas—very much like his own.

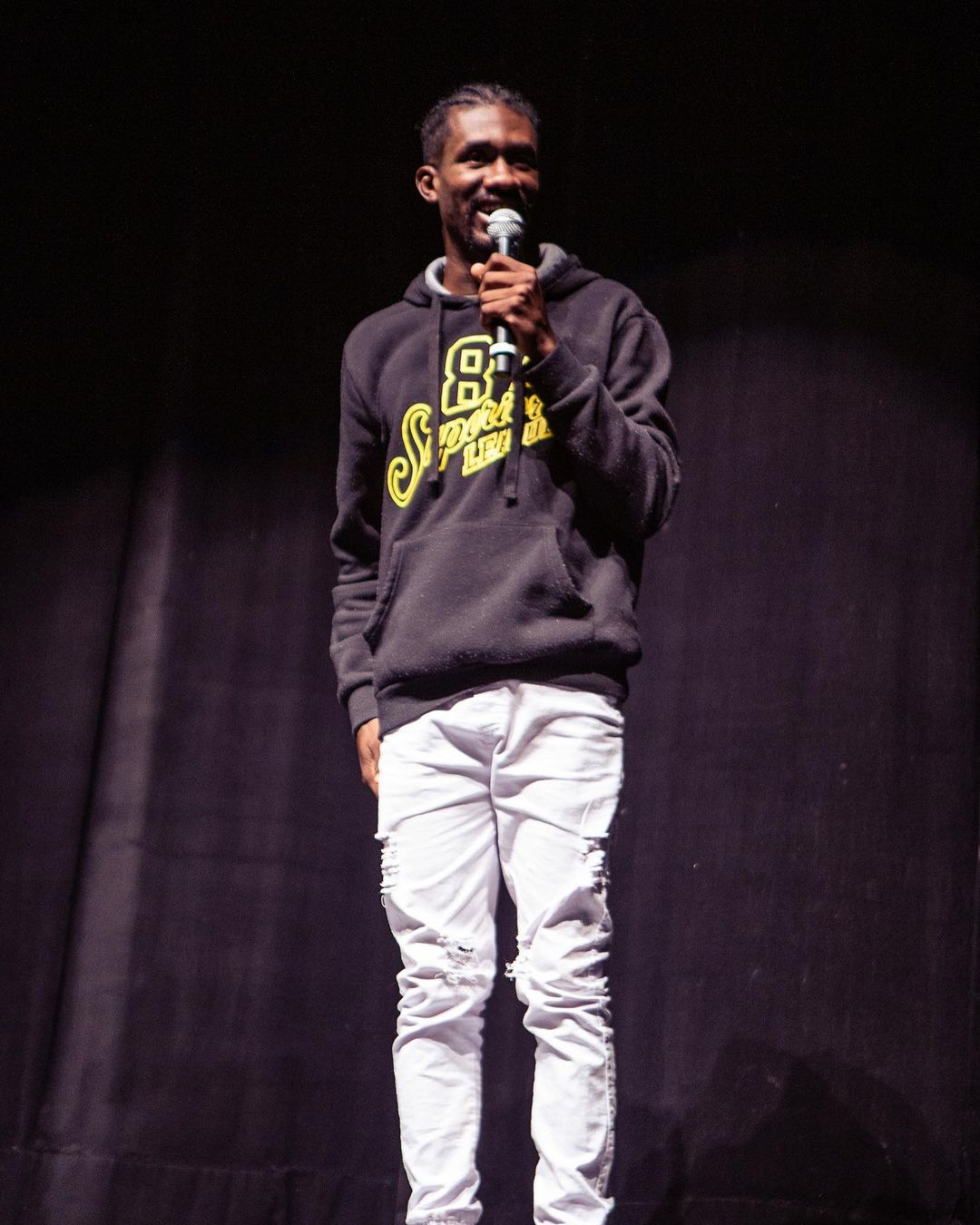

Mendes is not the only black artist using comedy as a tool for discussing social issues. Marcos Machado—who talks about racism and other social inequalities—explains how he experiences this social evil on a daily basis: “One day, coming back from the show, I got off at the Nilópolis station. There was a lady who thought I was going to rob her. She sped up, I sped up too, she crossed the street, I crossed the street too, she ran, and I ran too,” he recounts in one of his most recent posts. Everyday events summarized through comedy with some acidic touches has seen Machado gain a following of 187,000 on Instagram.

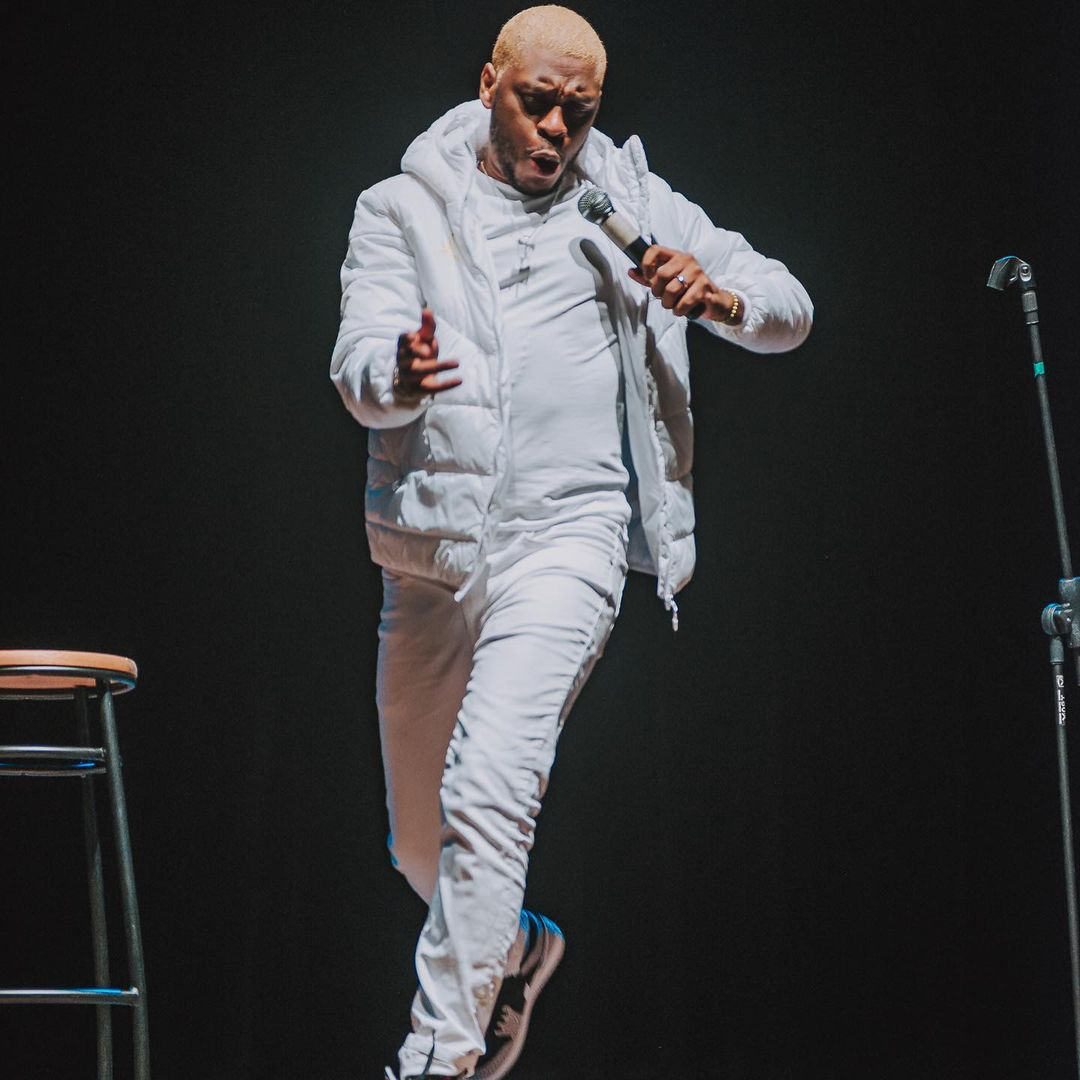

Despite there sometimes being films about their shows or lives, more than a million followers on their social networks, and the scope of their fight against racism conducted in a light and easy-going way, nothing prevents black comedians from being victims of racial discrimination. A recent and symbolic case was faced by comedian Yuri Marçal. He and his family received various insults and threats in October after he posted a video on his social media feeds talking about the second round of the 2022 elections, defending the importance of turning out to vote against President Jair Bolsonaro. As he explains in a video posted on his Instagram page, he has gotten used to receiving threats, but this was the first time that his family was threatened due to his work. These threats scared him so much that he chose to delete the videos.

“I do comedy to make people laugh, but… I posted a video talking about convincing people to change their votes… I received several insults and several threats… one of those threats was my fiancée’s license plate. And then it’s complicated because it involves another person. Because if I receive a threat—as I have many times and unfortunately I’ve normalized it—I manage and deal with the consequences. But I don’t want anyone, especially people I love, to be hurt because of something I have said. And so I decided to delete the video, along with other shorter videos as well, which are on other social media platforms.” — Yuri Marçal

Self-censorship unfortunately remains a very common self-preservation strategy among black Brazilian activists and comedians. As Marçal said in the video quoted above: “I do not want to be a martyr for anything, but right now I’ve decided to delete this video and soon this nightmare will be over.” In the video, he makes it clear that he thinks that such threats came from Bolsonaro supporters.

View this post on Instagram

Unfortunately this type of thing has been happening since yesterday. We have to protect ourselves! Cowardice is out there… Thanks so much for all the love! Soon, soon this will be over

According to Lívia Marques—a black and anti-racist psychologist—black comedians manage to establish a level of rapport with other black people that cannot be achieved by white comedians. This is due to the set of everyday experiences and violence shared by Afro-Brazilians and those who live in the peripheries of large cities in Brazil. It is about having a common repertoire and common values, a shared verbal and body language, and about coming from the same communities. Above all, it is about not viewing yourself in the subordinate position of the joke, humiliated for the white person’s laughter. It’s about laughing at yourself and your experiences, without dehumanizing yourself. It is, first and foremost, about laughing at the black peripheral experience from a place of respect and self-esteem, and not from a position of exoticism, stigma, criminalization, and racism.

“When white comedians tell a joke, the black person is often put in a place of humiliation—of being exposed within an act of humiliation. Black comedians, on the other hand, even talk about other minorities, but placing us all in a position from which we can make choices, confront scarcity, bring reflection and dialogue among ourselves, not out of shame, inferiority or mistrust.

“The movements that black comedians have been building are very interesting. They have been bringing art and belonging. A lot of people talk about identity, inclusion, and diversity. This is, above all, [about] belonging! It is about practicing laughter even in relation to the immense pain of the black population, which experiences daily silencing. Yuri Marçal, for example, creates humor that makes us think, that makes us reflect. It is not a [type of] humor that brings a feeling of marginalization. On the contrary, he makes the subject visible so that we can laugh without being excluded, without suffering humiliation.” — Lívia Marques

Beyond the issues of racism, threats and lack of respect, people in general tend to be more critical and give less recognition to black comedians for their work. Recently, Marcos Machado himself had his show in São Paulo canceled and replaced by a white comedian’s, without being told. The justification was that they had not sold enough tickets to keep his show in that time slot. He expressed regret that this had happened to him:

“I traveled to São Paulo. Two hours before the show they told me they were canceling, I said okay. Then followers messaged me saying that they had replaced my show with one from a white artist. And that they even used my artwork to advertise his show.”