Clique aqui para Português

Behind the scenes, Lula’s transition cabinet was charged with including greater numbers of underrepresented groups in federal ministries. Participating in the transition were indigenous intellectuals, quilombolas, Afro-Brazilian men and women, residents from favelas and peripheries, and representatives from civil society and social movements. With this the president-elect began giving a new face to the Esplanade of Ministries in the federal capital of Brasília—even though the typical picture of power in Brazil continues to be white and patriarchal.

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was elected with the support of a vast democratic front formed of left-wing, progressive, center, and right-wing parties, but also a strong affiliation by social movements and indigenous minorities, quilombolas, LGBTQIAP+, favela and periphery collectives and populations, as well as organizations that comprise Brazil’s Black Movement.

Brazil is formed of a majority black and female population, therefore the call for greater diversity in Lula’s government is to be expected.

Even if the transition included female, black and indigenous personalities and intellectuals—such as Anielle Franco, Iêda Leal, Preta Ferreira, Douglas Belchior and Silvio Almeida—who are very active in Brazilian politics, of the 320 names announced by president-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to compose the working groups in the transition cabinet, 207 were men and 113 were women. On average there were two men for every woman. Of those who form the cabinet, 144 members (48%) are from the southeast region of Brazil.

Dos 90 nomes de transição, 64 são homens. Não há mulheres no grupo de economia e de 13 no grupo de saúde só há 1 mulher. Negros/as e mulheres estão sobrerepresentados nas áreas de igualdade, mulheres e assistência social. Levantamento do @JornalOGlobo. https://t.co/KV5wu5odRx pic.twitter.com/P7MDIt06Zc

— Thiago Amparo (@thiamparo) November 13, 2022

Of the 90 names included in the transition, 64 are men. There are no women in the economy group and of 13 people in the health group, there is only one woman. Black men and women, and women [in general] are underrepresented in the areas of equality, women and social welfare. Survey by O Globo newspaper.

This composition of the transition cabinet was criticized because it is common for transition working group members to be subsequently announced for ministerial and government secretary positions. For this reason, Lula was openly called out in the press and behind the scenes by organizations that represent the Black Movement, indigenous peoples, and the LGBTQIAP+ population to form a new government that is truly representative of the Brazilian people.

On December 9, Lula announced the first five ministers of his government and confirmed that he would announce all chosen names by December 22, promising a government with “the face of Brazilian society in its entirety.”

When questioned about diversity in his government, Lula pointed out Flávio Dino, saying: “I don’t understand why you think this guy is white. If you ask IBGE (the Brazilian census bureau), they’ll say that, at the very least, he’s brown.” Dino was already announced as the future Minister of Justice and Public Security and self-identifies as a black man.

A study undertaken by the Update Institute‘s +Representation Program, revealed that a significant proportion of Brazilians support women and black people occupying ministerial roles in the elected government.

When combined with opinion polls, focus groups, and in-depth interviews with candidates in the last municipal elections, in 2020, the study offers a deeper insight into the need to increase electoral visibility of candidates from under-represented groups.

In total, 41% of poll respondents said they “agree or strongly agree with the statement” that the new president should assign women for half of the available government roles, even if they are not well known or do not have a background in politics. 39% “agreed or strongly agreed” that Lula should nominate black people for half of the ministerial positions, even if they are not known or have a background in politics.

Representation Matters

With each name announced to occupy positions in ministries, secretariats, advisory boards, contractees and other political roles in the senior executive branch, the criticism from popular movements has continued to intensify and the pressure for representation in the new government increases. And it is important to highlight that representation matters.

Margareth Menezes—a black singer from Bahia who participated in the culture working group alongside Federal Deputy Áurea Carolina—was invited and agreed to be the new minister of culture. The ministry will be recreated under Workers Party management following years of neglect.

Under Michel Temer’s administration, the Ministry of Culture (MinC) was merged with the Ministry of Education and was demoted to a secretariat. Only after strong mobilization did Temer recreate the ministry. With the election of Jair Bolsonaro, however, the MinC was once again dissolved and the Special Cultural Secretary was created, under the administration of the Ministry of Citizenship and, following that, the Ministry of Tourism.

The profile of the future minister has been celebrated: she is a black woman and human rights activist. Menezes was elected as one of the 100 most influential black people in the world, according to the Most Influential People of African Descent (MIPAD).

On December 16, the future Minister of Justice and Public Security, Flávio Dino, announced the members of his cabinet and the creation of a new secretariat. Among those announced are youth leaders and black activists who will be behind drafting national public security policies for the reduction of police lethality and for combating the genocide of the black population.

Lawyer Tamires Sampaio, 30, will coordinate the National Public Security and Citizenship Program (Pronasci), created in 2007 and currently inactive. Sampaio—resident of Guaianases, a favela in São Paulo’s east periphery—is coordinator of the National Anti-Racist Front and will lead the work to reduce crime rates in Brazil’s most violent metropolitan regions.

In an interview with Ponte Jornalismo, Sampaio states that the main challenge in this role is to build a notion of public security that is not based on repression and violence, but “through the guarantee of rights for the population, access to healthcare, education, housing, jobs, and income.”

Marivaldo Pereira—president of the Socialism and Liberty Party in the Federal District (PSOL-DF)—will lead the new Secretariat for Access to Justice, with a main role of coordinating the communication of the ministry with social movements.

Como compartilhei com vocês há uns dias, fui indicado pelo Ministro Flávio Dino para assumir a futura Secretaria de Acesso à Justiça no MJSP. Vim contar pra vocês um pouco mais desta nova Secretaria e um pouco mais da minha função nesse momento histórico! Vamo pra cima! ✊🏾 pic.twitter.com/qqvNSOB8kb

— Marivaldo Pereira (@Marivaldo4P) December 19, 2022

As I shared with you a few days ago, I was named by Minister Flávio Dino to the future Secretariat for Access to Justice within the Ministry of Justice and Public Security. I’m here now to tell you a bit more about the new secretariat and my role in this historical moment! Let’s do this!

Besides Sampaio and Pereira, Dino also announced Sheila de Carvalho—member of Uneafro Brasil, coordinator of the Institutional Violence Center of the Brazilian Bar Association, São Paulo Chapter (OAB-SP), and advisor to the Brazilian Association of Lawyers for Democracy, as well as being an activist in the Black Coalition for Rights. She was a member of the Justice and Public Security transition group and will now be Flávio Dino’s special advisor in the Ministry of Justice and president of the National Committee for Refugees (CONARE).

Com felicidade aceitei o convite do Ministro @FlavioDino pra ser assessora especial direta do Ministro p/assuntos de direitos humanos e diálogo com movimentos sociais, bem como Presidenta do CONARE. Juntos reconstruiremos as políticas de justiça no Brasilhttps://t.co/NdiZQBLMkT

— Sheila de Carvalho (@she_carvalho) December 16, 2022

It is with great joy that I have accepted Minister Flavio Dino’s invitation to be his special direct adviser for issues related to human rights and communication with social movements, besides being president of CONARE. Together we will rebuild Brazil’s justice policies.

In an open letter to Lula, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) nominated three indigenous leaders of different ethnicities for the president-elect to choose from to lead the first Ministry of Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples. The nominated leaders are: Weibe Tapeba, a lawyer and councilor from the Workers’ Party in Ceará (PT-CE); Sonia Guajajara, a teacher, educator and nurse from Maranhão but currently based in São Paulo and affiliated to the PSOL-SP; and Joenia Wapichana (REDE-RR)—the first indigenous female lawyer in Brazil and first indigenous woman to be elected federal deputy. Guajajara and Wapichana are part of Lula’s transition cabinet in the technical group for Indigenous Peoples alongside three other indigenous leaders: Benki Piyãko, Célia Xakriabá, and Davi Kopenawa Yanomami.

It is also worth noting the participation of those born and raised in favelas, intellectuals and activists from peripheries, in the cabinet, such as Sabrina Santos, member of the Heliópolis Residents’ Union (Unas).

Sabrina Santos, 20 anos é pesquisadora do projeto da UNAS, #DeOlhoNaQuebrada e estudante de ciências econômicas e políticas públicas da UFABC. Hoje ela foi anunciada pelo vice-presidente eleito @geraldoalckmin como membra do governo de transição no GT de juventude. pic.twitter.com/Nj3sDNp7he

— UNAS Heliopolis (@UNAS_Heliopolis) November 14, 2022

Sabrina Santos, 20, is a researcher for the #EyesOnTheHood UNAS project and a student of economic sciences and public policy at UFABC. Today she was announced by vice-president-elect @geraldoalckmin as member of the transition government in the youth working group.

The Racial Equality transition group had big names such as: Nilma Lino Gomes, former Women, Racial Equality, and Human Rights Minister; Givânia Maria Silva, quilombola educator and Sociology PhD; Iêda Leal, pedagogue and National Coordinator for the Unified Black Movement (MNU); and Preta Ferreira, activist of the black and housing movements, detained in 2019 for 109 days for being part of the Homeless Workers’ Movement (MTST) and the Fight for Housing Front in the city of São Paulo.

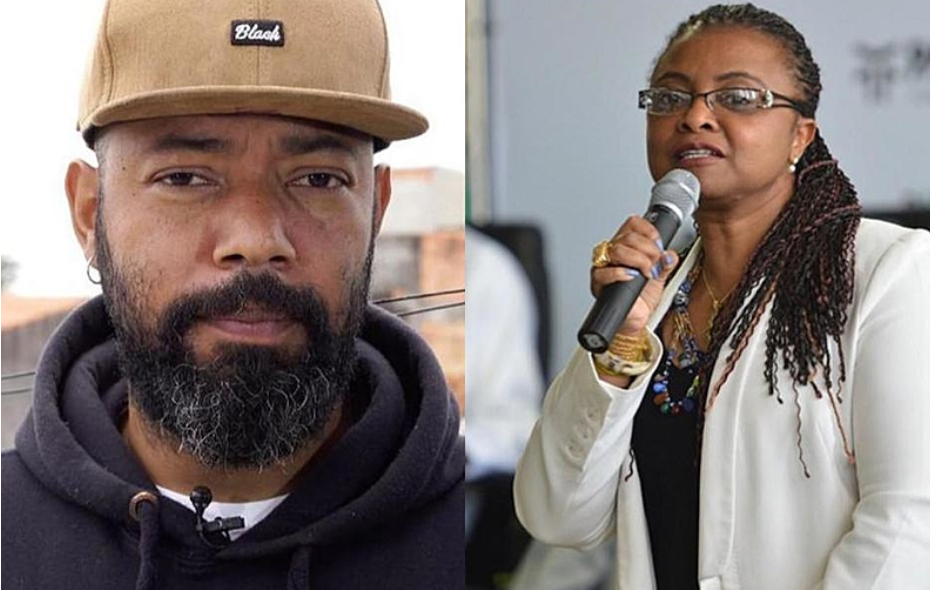

Besides Sheila Carvalho, other members of the Black Coalition for Rights participated in the transition groups. Among them were Douglas Belchior, history teacher and founder of Uneafro Brasil, and Thiago Tobias, the Coalition’s lawyer.

After participating in the Women’s Transition Group alongside nine other members, Anielle Franco—journalist and researcher with a master’s degree in Ethnic-Racial Relations, and born and raised in the Complexo da Maré that encompasses 16 favelas in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone—will take charge of the new government’s future Ministry of Racial Equality.

Iraneide Soares da Silva—doctor of history and member of the Sankofa Center for Studies and Research in History and Memory of Slavery and Post-Abolition at the State University of Piauí (UESPI)—participated in the transition group for Science, Technology, and Innovation. The leadership of the future Ministry of Science and Technology will be in the hands of Luciana Santos—member of the government transition group’s political counsel and current vice-governor of the state of Pernambuco.

In the transition group for the Ministry of Human Rights, the participation of Silvio Luiz de Almeida—one of the most renowned black intellectuals in the country—is noteworthy. A lawyer and former professor at Columbia and Duke, universities in the United States, Almeida is author of the widely read reference book Structural Racism. Despite upsetting some Workers’ Party members who, according to CNN Brasil, would have preferred a politician in the role, Silvio Luiz de Almeida’s appointment was confirmed on December 22 when the Minister of Human Rights was announced.

Ministry Nominations and a Glimpse of the Future

The new government will be composed of 37 ministries. The creation of new ministries corresponds to promises made during the campaign, but will not represent an increase in roles under the public federal administration. Until now, the 21 ministers announced by president-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva include ten Workers’ Party members, six women, four Afro-Brazilians, and one indigenous person. Lula announced these future ministers in a press conference on December 22, with 16 yet to be announced.

Lula has been charged with ensuring more diversity and the 21 ministers announced have not yet resolved the issue. In terms of gender, 15 men have been nominated as ministers, with only six women. Among them is Anielle Franco, until now director of the Marielle Franco Institute, who was appointed Minister of Racial Equality. Franco is the sister of Marielle Franco—the city counselor who was brutally assassinated in Rio de Janeiro on March 14, 2018. Almost five years after her murder, the crime is still being investigated and no suspect has been charged.

In an announcement made on Twitter, Anielle stated that she will create an administration aligned to the other ministries and secretariats: “It will not be an isolated ministry. We will work with all other ministries to make up for the regression that has occurred in the last few years and move forward in a manner that is urgent, necessary, and unprecedented for the guarantee of rights and dignity for our people and building the Brazil of the future.”

She also explained why she accepted the role of minister:

“I received President Lula’s invitation to be Minister of Racial Equality. After reflecting with my family and friends from my life’s journey and [various] movements, I accepted the challenge on behalf of my sister’s name and memory and of over 115 million black people in Brazil that are the majority of the population and need a government that cares about their rights to a good life, opportunities, security, food, education, jobs, culture, and dignity.”

The Marielle Franco Institute shared a post remembering the last talk given by Marielle Franco at Casa das Pretas prior to her assassination, about “young black women shaking up structures.”

O ano era 2018 e essa foi a última fala de Marielle no evento do seu mandato “Jovens negras movendo as estruturas”.

Quando falamos de mais de nós na política, falamos sobre reparação, sobre justiça e democracia. pic.twitter.com/Ywl3wzhOVW

— Instituto Marielle Franco (@inst_marielle) December 22, 2022

The year was 2018 and this was Marielle’s last speech at her mandate’s event “Young black women shaking up structures.” When we talk about more of us being in politics, we’re talking about reparation, justice and democracy.

Another big name in the black movement chosen for a ministry, Silvio Almeida, stated in a Twitter post: “It is with immense honor and responsibility that I take on the role assigned to me by President @LulaOficial to serve my country as Minister of Human Rights. We have a huge job ahead of us, but I hold the hope of bringing dignity to the Brazilian people.”

Elected by a broad democratic front, so far Lula has shown that the government will have the face of the Workers’ Party, without compromising a possible government with a center-right orientation instead of center-left.

Of the 37 ministers that form his cabinet, seven are from the Workers’ Party—the party with most participants. No centrist party has been considered so far. In ethnic and gender terms, there are ten white men, three self-declared as brown (Flávio Dino, Rui Costa and Jorge Messias), one black man, Sílvio Almeida, and one indigenous person, Wellington Dias. Among the six women, Margareth Menezes and Anielle France are black, and Luciana self-declares as brown.

With 16 roles yet to be announced, the expectation remains for diversity in the selection that truly represents Brazilian society.

The article was originally published on December 29, 2022.

About the author: Tatiana Lima is a journalist and popular communicator at heart. A black feminist, member of Complexo do Alemão’s Researchers in Movement Study Group, she is currently special reporter with RioOnWatch. A fair-skinned black woman, born and raised in a favela, Lima currently lives in Rio’s periphery and is a doctoral student at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF).