Over two days last week, the favelas of Maré in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro, suffered police operations carried out in at least 13 of the 16 communities which make up the complex. These raids affect lives across the entire territory in various ways, including the closing down of public health facilities, for example. Operations threaten residents’ right to come and go. Schools close or have their activities interrupted, which directly impacts children’s education, not to mention the trauma from experiencing violent police operations day in and day out.

Another, unfortunately recurring, problem that Maré residents have to deal with is negligence by utilities contracted to provide public services such as water and electricity—which are basic social rights. Although they impact residents negatively year round, the problems caused by the lack of water service from Águas do Rio or electric utility Light are always worse in summer, when it is hotter and more people are at home.

In December 2022, for example, RioOnWatch reported that the water shortage in Maré lasted at least two weeks. Raniery Soares, 25, a resident of Parque Maré, had no water for 22 days. All this was due to Águas do Rio’s delay in repairing a leak in the Maré sub-main in the Parque Maré area. During this episode, there were reports of water shortages in the favelas of Parque União, Rubens Vaz, Parque Maré, Nova Holanda, Baixa do Sapateiro, and Morro do Timbau.

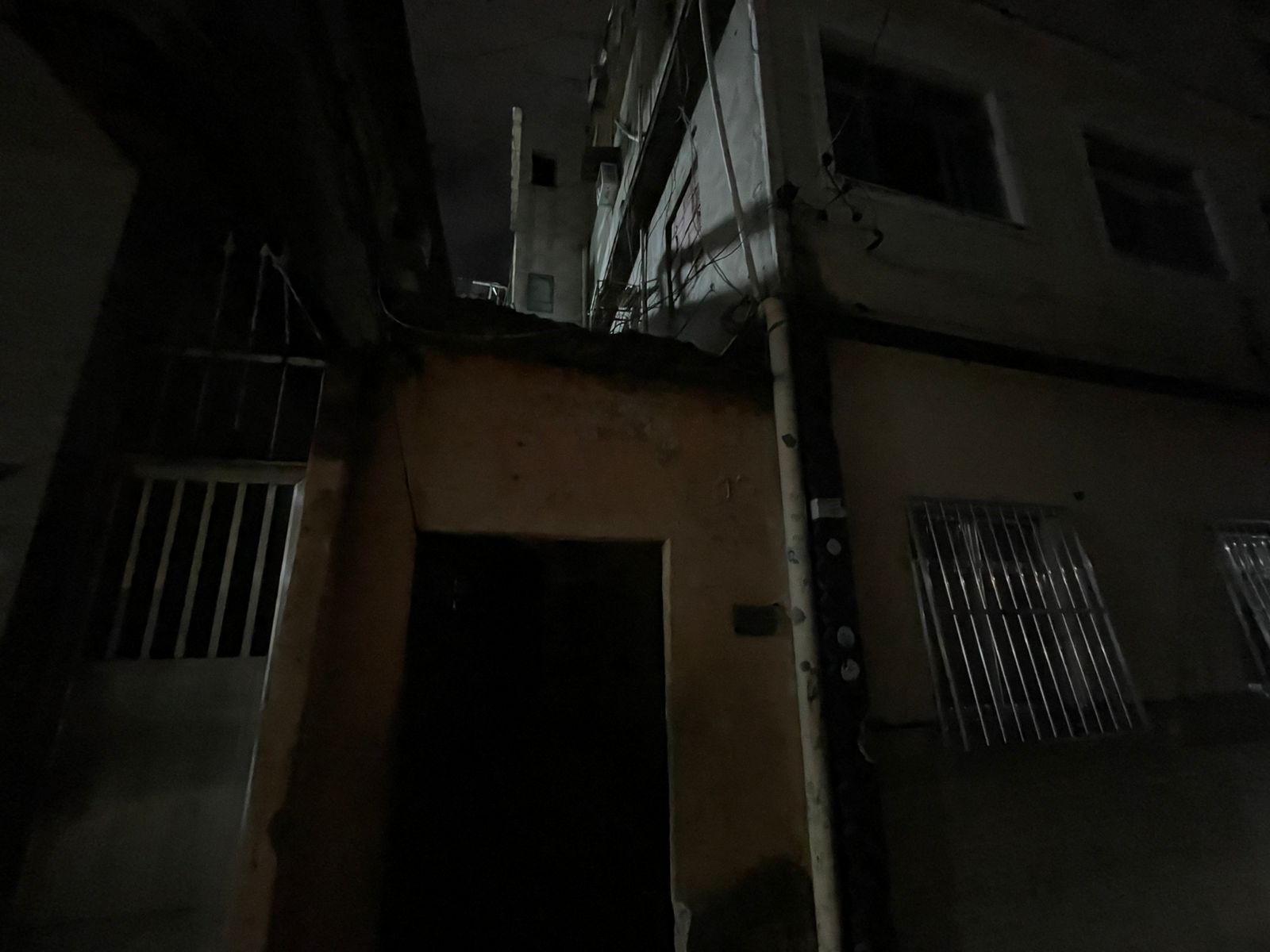

This time, residents report that they have been without electricity for at least four days. With no response from Light, support from public agencies, or visibility in the mainstream media, residents find themselves alone in the dark and heat in the midst of two days of police operations.

“Parque Maré has always been very vulnerable due to power outages. In some streets, transformers and lamp posts always catch fire due to lack of investment and maintenance in the territory.” — Raniery Soares

According to resident reports, around 35 houses in Parque Maré are without electricity, located on the streets Princesa Isabel, Tatajuba, São Jorge, and Beira Mar. In addition to Light, residents sought help through the North Zone Sub-Mayor’s Office, which provided the contact of an advisor named Fábio Barbosa, supposedly responsible for Maré, but that could not be reached. The Parque Maré Residents’ Association was also contacted, but its representatives declared they could not help. Beyond Parque Maré, residents from some regions in Vila do João are also reporting power outages.

Even with the formal calls for repair by residents and numerous service request orders generated, Light still has not given a timeframe for restoring the power supply in these areas. According to the residents interviewed, they made on average ten calls over four days requesting repairs, with not a single response.

“[The power outage] affects everything! We can’t sleep, it spoils the food in my refrigerator. I’ve got no water because I live on the third floor and water doesn’t reach me without a pump.” — Renata Estevão

Renata Estevão, 38, is a resident of Parque Maré and has two children. She explained she has spent a few hours of the day at a friend’s house which has electricity. However, it is not enough. The buckets of water that Renata fetches for consumption at home are not enough for all the clothes she needs to wash, for cooking, personal hygiene, and cleaning the house.

“They’re not coming because they don’t think it’s important. It’s inhumane to leave people for four days without electricity, children without electricity at home, not able to go to school due to the police operation. What are we expected to do?” — Renata Estevão

During the second day of police operations, on Friday, March 3, residents reported that a team from Light turned up at the community. They had been assigned to carry out electricity repairs in the streets but were prevented from fulfilling the service by police on the grounds that the territory was in conflict.

It is clear how, in the end, all the negligence that affects the territory is interconnected in some way. The three mentioned here—police operations, lack of water, and lack of electricity—are disruptions that deprive the favela of a normal routine. For example, if the resident has no electricity, they have no water, because the low quality of the water service requires almost all houses to use water pumps to bring the water from the street up to the water tanks.

However, even with water and electricity, if there is a police operation going on, residents are unable to follow their normal routine. And if there is a problem with water, electricity, Internet, cell phone signal, or any other service—like last week in Parque Maré—residents continue to be cut off from services during the police operation due to the inability of the utility’s technicians to work. On occasion, as ocurred last week, police operations perpetuate the lack of services and access.

Therefore, it is essential to discuss the scope of public policies for favela territories, besides drawing attention to the inequality in comparison with other spaces in the city. From a general Rio perspective, the idea of a middle class neighborhood in the South Zone spending four days with no electricity, no effective response from Light, and no exhaustive media coverage would be absurd. Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for favela residents to find themselves in situations like this.

This can never be normalized. It is important to be aware and demand that the the basic rights guaranteed to any Brazilian citizen are fulfilled by the authorities, agencies, and companies responsible.

About the author: Juliana Pinho is a resident of Nova Holanda, one of the favelas that make up Complexo da Maré, and is a sociologist (UFRJ) and journalism student (UCAM). A popular communicator and community organizer, Pinho co-founded the Maré Mobilization Front, is a member of the Palafitas Agency, and is responsible for management and planning of the For Her project. Currently, she manages NGO Fight For Peace‘s portfolio and is a reporter for the Entretetizei portal.