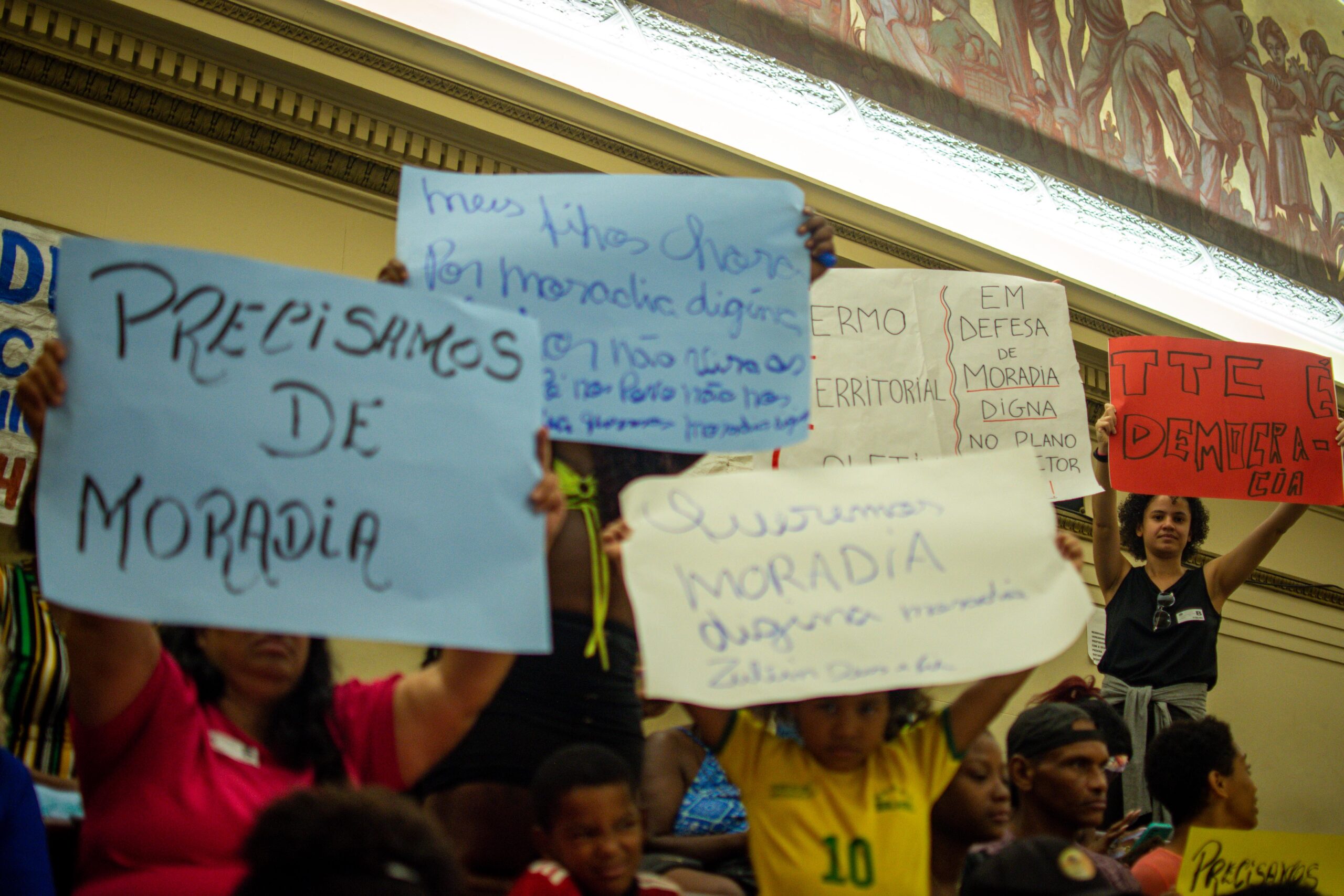

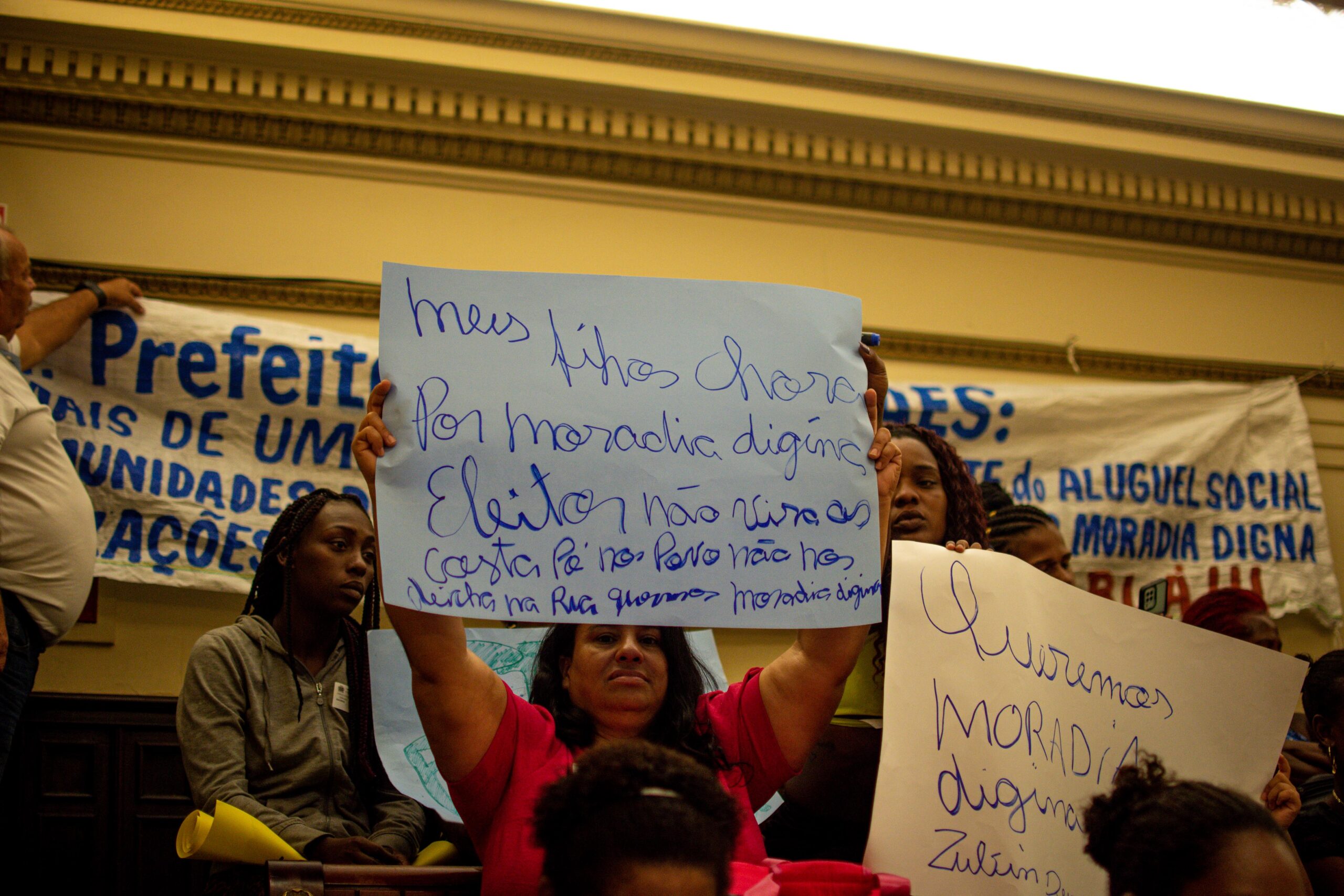

The Rio de Janeiro City Council Chambers were filled past capacity the first two Wednesdays in April as over 120 people mobilized for the right to housing. Filling both the galleries and plenary, the public made noise and put pressure on officials during the 28th and 29th Master Plan Special Commission Public Hearings on April 5 and 12. The hearings concerned urban policy mechanisms and unilateral changes made by City Hall in their revision of the draft bill of Rio de Janeiro’s City Master Plan (PLC nº 44/2021).

28th Public Hearing on April 5: The Urgency of Guaranteeing Affordable Housing and Reincorporating the CLT into the Master Plan

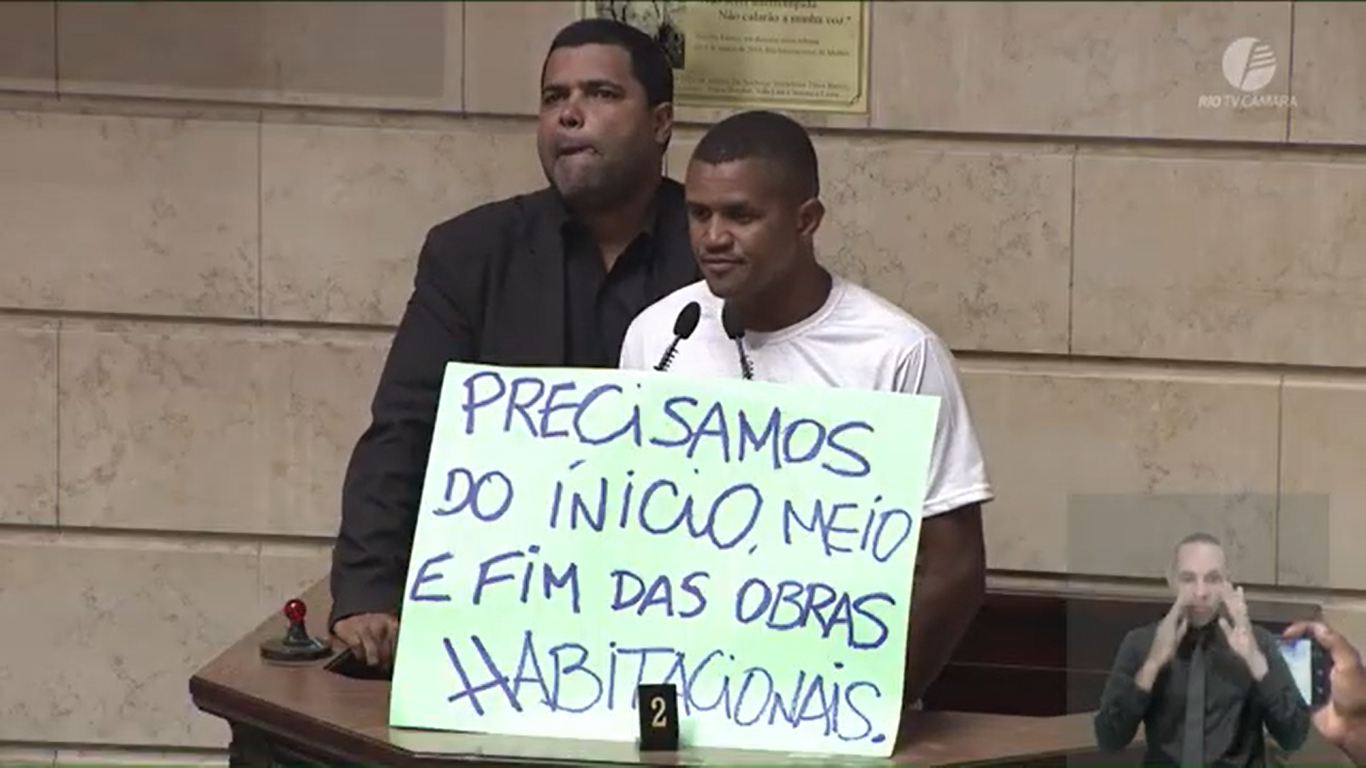

For many participants, the hearing on April 5 started in the entrance line as over 60 people waited to access the City Council Chambers’ B Gallery after the A Gallery had been filled. The queue moved very slowly with those waiting believing this was an attempt to demotivate them. Security guards initially denied entry to 15, but people in the gallery returned to inform them—including some due to speak in the plenary—that there were still vacant seats. After over 30 minutes of waiting and pressure, the guards allowed those waiting to enter. This was at 11:30am, halfway through the hearing. Only then had the 120 people in the line been allowed to enter.

Residents of favelas and occupations continued to arrive, however, especially those coming from more distant areas of the city in the North and West Zones. Though there were still vacant seats in the galleries, around 40 residents of favelas and occupations were blocked from entering. According to security guards, this was due to the capacity established by the fire department. “We arrived late because the train was delayed, we’ve come a long way for this hearing,” complained a resident of an occupation in Rio’s West Zone, who preferred not to be identified.

Those who managed to get in heard talks from various community representatives, residents, and professionals: Luiz Cláudio da Silva from Vila Autódromo; Emília Sousa from the Horto community and Popular Council leader; Jurema Constâncio, resident of the Shangri-lá cooperative and National Union for Popular Housing (UNMP) leader; Paula Carvalho, from the Favelas Pastoral Committee; Flávio Braga de Oliveira, representative of families living on social rent in Jacarepaguá; Licínio Rogério, president of the Rio de Janeiro City Federation of Neighborhood Associations; Michele Cruz de Abreu and Sara Ferreira do Amaral from the Zumbi dos Palmares Occupation; Paulinho Soró from the Jambalaia Occupation in the West Zone; Tarcyla Fidalgo from the Favela-Community Land Trust Project*; Viviane Silva Santos Tardelli, public defender from the Land and Housing Nucleus (NUTH); Marcela Marques Abla, president of the Brazilian Institute of Architects (IAB); Henrique Barandier from the Brazilian Institute of Municipal Administration (IBAM); Augusto Ivan Pinheiro, Municipal Urban Planning Secretary; Valéria Hazan, Macro Planning Manager at the Municipal Urban Planning Secretariat (SMPU); Luiz Roberto da Matta, Rio de Janeiro municipal prosecutor; Washington Fajardo, former Rio de Janeiro Urban Planning Secretary; and Thiago Ramos Dias, Executive Undersecretary at the Municipal Secretariat for Economic Development, Innovation, and Streamlining (SMDEIS).

Many talks advocated for the right to housing in Rio de Janeiro and demanded that this be a central aspect of the city’s Master Plan, ahead of other urban development considerations due to the historical deficit in housing and quality urban infrastructure in the city. The numerous amendments sent by City Hall at the last minute were also denounced by many who spoke, particularly highlighting the removal of the Community Land Trust (CLT) from the Master Plan.

Tarcyla Fidalgo is coordinator of the Favela-CLT Project, a diverse and broad working group of civil society groups and professionals who have been introducing this high-potential tool in Brazil over the past five years. Fidalgo criticized the removal of the chapter on Community Land Trusts from the Master Plan and the lack of clarity from City Hall as to its removal. The CLT Working Group of residents, leaders, and professionals participated extensively in the Master Plan preparatory meetings and the tool was embraced in its entirety in the version sent to the Mayor at the end of 2021. She remembered a municipal prosecutor giving a positive opinion about incorporating the model into the Master Plan as a public policy option and way of resident self-management for the right to stay in their locations. But, even so:

“The Community Land Trust was the only mechanism excluded from the Master Plan… We’re here out of respect for the people who need to understand this technical debate that removes people from their houses, that means people are evicted from their homes… Up to now, the justification [for the removal of the CLT] that I’ve received is that it was a ‘refining of the text.’ But here today, together with all of you, I’ve learned that it was apparently a legal issue… Prosecutor da Matta himself, who issued a 48-page opinion on the Master Plan with six pages dedicated to the Community Land Trust, said that… yes, it is possible for it to be in the Master Plan… What then, is the real reason for which the CLT was removed? It’s not a legal issue. It’s not a refining of the text. So what happened? We need a response on this, because the CLT’s inclusion in the Plan is the result of popular participation in the Master Plan revision process and the people need to understand why it’s being removed. There’s no barrier to it being in a Master Plan, in fact it’s already in the [master plan of neighboring municipality] São João de Meriti.”

To Fidalgo, a lawyer and urban planner, an in-depth discussion about the CLT’s inclusion is vital for Rio’s favelas and occupations, and “it’s not something to be imposed… The CLT requires partnership and has a community-strengthening character… According to Prosecutor da Matta, the CLT is a voluntary model and must be so. Even if we have the legislation, it must be something people choose, otherwise it doesn’t make sense.”

Prosecutor Luiz Roberto da Matta evaluated that the CLT’s greatest asset, besides guaranteeing people’s ability to stay in their communities, is people’s participation in all its stages, including in proposing its incorporation in the Master Plan:

“The proposal to include the Community Land Trust in the Master Plan is a reflection of people’s participation in revising it [the Plan]. This participation is prescribed by Article 40 in the City Statute, and has meant this new instrument can contribute to advancing the right to the city through a model of collective land management in areas with predominantly vulnerable populations.”

This is even more important considering federal legislation (Law 13,465/17) in Brazil which establishes a new framework for land titling, making the process easier and cheaper. The framework is being finalized in Rio de Janeiro. This law creates a trend of increased titling processes for individual property. However in the context of around 1,000 favelas in the city of Rio, individual titles independente of other measures which guarantee the right to stay will increase the risk of gentrification—which Fidalgo simply terms “market eviction.”

“The new land titling legislation [means titling] is no longer seen as a long, complex process connected to infrastructure improvements and comes to be viewed as simply the issuing of titles and documents with the logic of full ownership… But we live in a very unequal city… [where] issuing titles in an area of the South Zone or in an area of the suburbs or favelas will have very distinct outcomes. We know the real estate market has different interests in different regions of the city and that issuing individual titles, this land titling that everyone wants, could represent a large threat to the permanence of many communities and many people who currently somehow manage to guarantee their housing in areas with infrastructure, where they can enjoy urban amenities, which should be available to all but we know aren’t. This is the logic that produces cities all around the world, not just in Rio de Janeiro.” — Tarcyla Fidalgo

In Rio, we experience two main threats to the right to remain of residents in their communities, two sources which deny the right to housing: government action through forced evictions and the real estate market which drives gentrification.

“We have a problem with the extent to which these thousands of residents will have secure land ownership over the coming years… Full ownership is an option, but it’s perhaps not the best option for the whole city or for all its residents. And many of them are here today. I see signs in the gallery defending the CLT which seem to agree and want another model to guarantee their housing.” — Tarcyla Fidalgo

What is the Community Land Trust (CLT)?

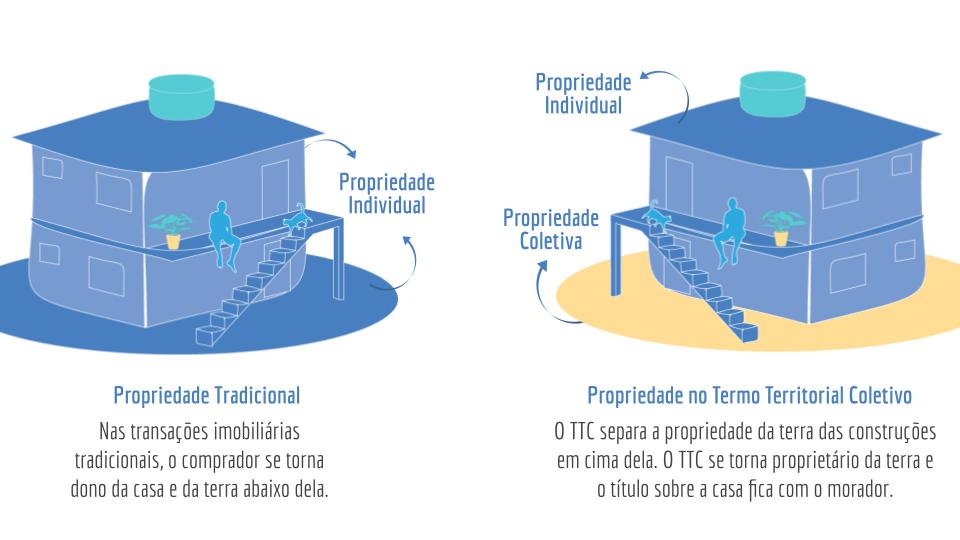

The Termo Territorial Coletivo (TTC) is the Brazilian version of the Community Land Trust (CLT), a land management model increasingly used around the world to ensure affordable housing. It works by forming a legal entity whose board is typically made up of residents and allies and which owns the land and administers it in accordance with residents’ interests. The organization cannot sell the land, just undertake its management. In this way, the land is governed by residents, removed from the market, and is separate from property values and protected from speculation. Meanwhile residents own their residences and plots above the surface of that land and are able to remain or sell, mortgage, or pass them on to their children. It is among the most robust models of land titling in relation to the aim of allowing residents to remain in their communities of origin in those contexts in which it has already been applied around the world.

Emerging in the context of the civil rights movement in the United States at the end of the 1960s, the CLT spread across the country where there are hundreds of CLTs in operation today, both in cities and rural areas. In recent decades, there has been a rapid spread of CLTs around the world, and there are currently CLTs in various countries including the UK, Belgium, France, Australia, Kenya, and Puerto Rico. In Rio de Janeiro, there are communities in the community organizing and development phase of becoming CLT pilot projects.

“The resident has the full right to sell their home, rent it out, or leave the house as inheritance. But the land, which is where land value appreciation comes in through public investment, belongs to the community by way of a legal entity… We’re talking about full ownership but we’re separating full ownership by a legal entity and surface rights which allow residents the individual freedom to sell, move, rent out, do whatever they like. It’s an innovative arrangement in Brazil, but it’s already included in the UN’s New Urban Agenda.” — Tarcyla Fidalgo

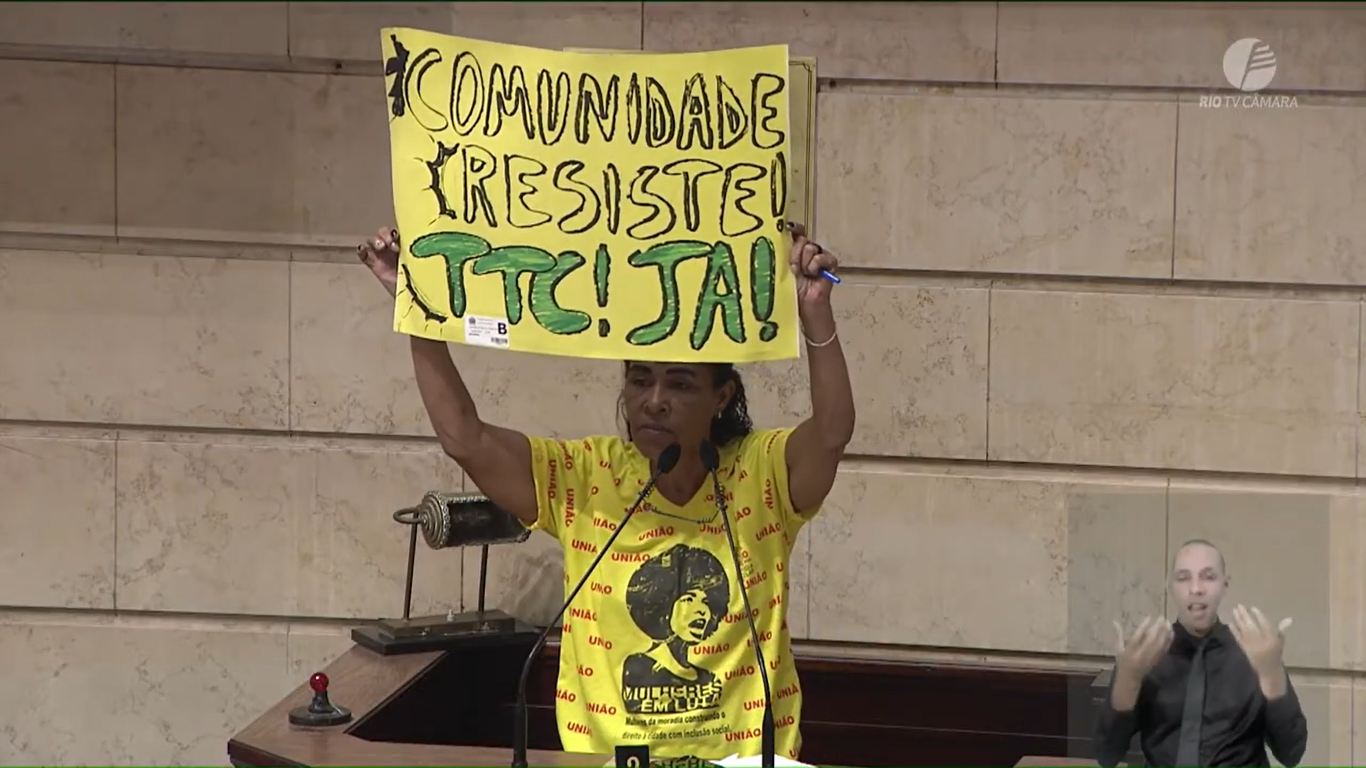

The first public hearing on the Community Land Trust was held at the Rio de Janeiro City Council on September 28, 2021. Since then, the model has been called for by popular demand to be included in the city’s Master Plan. The instrument’s inclusion in the Rio de Janeiro City Master Plan Draft Bill (PLC nº 44/2021) was debated through the Rio de Janeiro City Council’s Permanent Commission for Urban Issues and Special Commission for the Right to Adequate Housing in partnership with professional allies, residents, community leaders, and civil society and city government representatives. At the time, the hearing was organized by City Councilor Tainá de Paula, President of the Permanent Commission for Urban Issues, alongside Councilor Reimont, who was then President of the Special Housing Committee. Also present were councilors Eliel do Carmo, before leaving the role, and Mônica Benício, the only one who today remains as an elected city official.

In 2023, some alternates have become new councilors, assuming roles in place of councilors that have been elected federal deputies or taken roles in government. These include Monica Cunha—one of the few elected officials present at the public hearing on April 5. In her talk, Cunha defended the CLT and highlighted her contentment with the public participation in the galleries.

“The CLT needs to be effectively reinstated in the Master Plan. We have no doubt about this. We don’t just want to be labor. We want existing laws to be put into practice so we can benefit from the land that is ours, and not see any more real estate speculation.”

In addition to Monica Cunha, Councilor Rafael Aloisio Freitas, first secretary of the Council’s board of directors and president of the Master Plan Special Committee, was present and chaired the hearing. Councilors Thais Ferreira, Edson Santos, and Pedro Duarte also attended in person and gave talks. Councilor Tânia Bastos, despite not participating in the session, temporarily presided over the hearing in Freitas’ brief absence. At least nine other councilors attended the hearing remotely, as was announced at the start of the hearing and could be seen on the board’s computer screen. However, everyone had their cameras off for most of the hearing and did not speak up.

Two people gave remote talks that caused commotion among the public, in support or in disagreement: former Rio Urban Planning Secretary Washington Fajardo and the Executive Undersecretary at the Municipal Secretariat for Economic Development, Innovation and Streamlining (SMDEIS) Thiago Ramos Dias. Fajardo reinforced his support for the innovations brought by the CLT model and again questioned its removal from the Master Plan draft bill. According to Washington Fajardo:

“The CLT’s introduction needs to be pragmatic. It is a model of land regularization and [provides] the possibility of advancing the inclusion of 25% of the city’s population with a more sophisticated technical solution and that many countries use.”

For Fajardo, there is no need to fear the model or create rumors: “These rumors start haunting [processes] and sometimes even take down secretaries and change the Master Plan out of fear of a revolution. The CLT is quite objective in that it’s not just a policy, but is able to be financed and implemented.”

Thiago Ramos Dias was pointed out, especially in the Council’s galleries, as one of the main people responsible for the removal of the Community Land Trust from the Rio de Janeiro City Master Plan. Despite this, and after so many requests for clarification, he did not comment on the reasons for the model’s removal.

Emília Sousa from Horto and the Popular Council expressed being tired of the bureaucratic discussion and the technicalities that generally take center stage in these debates, especially in talks such as that of Undersecretary Thiago Ramos Dias. She demanded there be money for investments in affordable housing, especially in Central Rio.

“I came to speak more directly about our concrete demands for this Master Plan… people in the favelas, Black people, who suffer from discrimination in this city, who suffer from the lack of proposals for the right to the city and right to housing… We want money to be included in the Master Plan, through whatever instrument it may be, for building affordable housing in the city’s central region. And that, councilors and mayor, is what we need!” — Emília Sousa

Jurema da Silva Constâncio is a National Union for Popular Housing (UNMP) leader and resident of the Shangri-lá community, a housing cooperative that is organizing to build a CLT in the West Zone of Rio. She spoke with the aim of making known her concern about the model’s removal from the Master Plan in a top-down, authoritarian manner. She highlighted that this approach by Eduardo Paes’ administration denies residents’ self-management over their own territories.

“The CLT does not come with a predesigned, top-down proposal meant to be rammed down our throats. It gives us the opportunity to discuss what we want to do. For us, this allows our community to stay in our space without real estate speculation.” — Jurema da Silva Constâncio

At the end of the public hearing, Luiz Cláudio da Silva from Vila Autódromo, one of the leaders of the Evictions Museum, closed the talks by favela residents by calling for the CLT to be reincorporated into the Master Plan.

“We don’t see a significant advance [in discussions about housing]… My home was demolished, I was on the streets because of the Olympics. An ‘injunction for public purposes.’ But there’s nothing public there now, it’s only bushes. It was really just cruelty because of the real estate market… So, we have to ask: ‘Who has an interest, really, in removing the CLT from the Master Plan?’… Without any obvious explanation… This tool… solidifies the history of families in a community… Rio de Janeiro has to have a more humane outlook… Let’s stop being a tourist city, focusing on the South Zone and on the South Zone only while the rest [of the city] suffers… The CLT is an instrument that gives hope to favelas when the market comes too close and tries to remove them, like what happened in Vila Autódromo…” — Luiz Cláudio da Silva

Watch the Recording of the Public Hearing on April 5 Here.

29th Public Hearing on April 12: Other Mechanisms for the Right to Housing

The public hearing on April 12 was the second day of discussions on the Master Plan’s urban policy instruments, with the session’s president Rafael Aloísio Freitas the only councilor in attendance. Eleven other councilors attended virtually via Zoom. Later, one of the eleven, Councilor Thais Ferreira, arrived at the Chambers and spoke. No other councilor was present at the April 12 hearing. Some members of the municipal executive branch from the April 5 hearing spoke again: executive undersecretary of the Municipal Secretariat for Economic Development, Innovation and Streamlining Thiago Ramos Dias, macro planning manager of the Municipal Urban Planning Secretariat, Valéria Hazan, and Municipal Urban Planning Secretary Ivan Pinheiro.

After acknowledging those present, Freitas invited residents of favelas and occupations, social movement leaders, authorities, and professionals signed up to speak on April 5 but who were unable due to high demand, to complete the discussions on urban policy instruments and changes made by City Hall to the original Master Plan proposal. The platform was taken up by: Marcela Marques Abla, president of the Brazilian Institute of Architects (IAB); Tarcyla Fidalgo from the Brazilian Institute of Urban Planning Law (IBDU) and the Favela-Community Land Trust Project (Favela-CLT); Mauro Salinas, director of the Rio de Janeiro City Federation of Neighborhood Associations; Adrian dos Santos from the Movement for the Fight for Neighborhoods, Villages, and Favelas (MLB); Rose Compans of the Architecture and Urbanism Council; Maria da Penha Macena, community leader from Vila Autódromo, the Popular Council, and the Evictions Museum; Jurema Francisco Ferreira from the Morar Feliz Occupation; Mariana Trotta, professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and coordinator of the Luísa Mahin Nucleus for Popular Legal Advice (NAJUP); Raphael Pazos, founder of the Rio de Janeiro Cycling Safety Commission (CSC-RJ); Viviane Zampieri, founder of Bike on Track and member of CSC-RJ; Elizabeth Alves Bezerra from the Rio Articulation for Socio-Environmental Justice and SOS Vargens Movement; Luciane Wanderley de Jong from the São Cristóvão Neighborhood Association; William Evangelista Freire from the Zumbi Occupation; Paulo Roberto da Silva Machado from the Trapicheiros Residents’ Association; and Emília Sousa, resident of the Horto community and Popular Council leader.

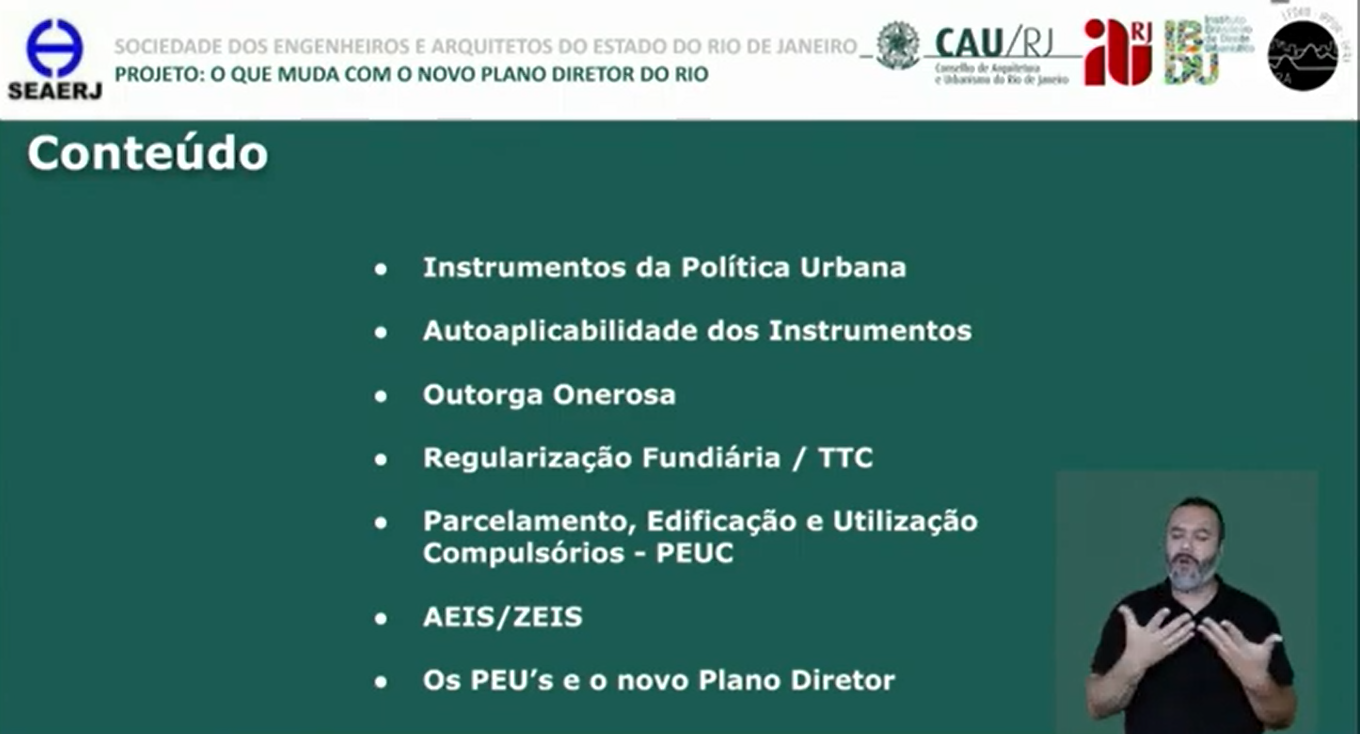

Opening the day’s talks, Marcela Marques Abla and Tarcyla Fidalgo were invited to analyze City Hall’s amendments to the Master Plan draft bill. Abla analyzed the project via three axes: Applicability of Urban Instruments; Analysis of Proposals to Define Areas of Special Interest and Zones of Special Social Interest; and Analysis of Zoning Changes.

Fidalgo discussed the self-applicability of urban policy instruments, arguing for the need to rethink urban policy mechanisms.

“The most interesting thing is that the instruments that are of interest to the real estate market have greater power to put their agendas before the legislature, often via decree by City Hall. The instruments of social interest, in particular those aimed at housing, require complex procedures, dozens of hearings like these, where people need to miss work to be here at 10am on a Wednesday morning.”

Fidalgo called for the approval, application, or strengthening of several urban policy instruments. The first example given is the Outorga Onerosa do Direito de Construir (OODC), in English known as “onerous grants and the transfer of the right to construct,” which is still not applied by the city of Rio despite being approved over 20 years ago in the City Statute. Rio city government claims it needs five years before starting to charge this fee from the city’s building firms. According to Fidalgo, this claim is made with no supporting studies. The waiver represents a problem for municipal revenue, without which there could be more investments in areas such as health, education, and housing. In addition, the urban planner defended how the OODC can drive urban growth. Depending on where and how it is applied, it can induce the market to produce housing or commercial units in certain areas of the city.

Fidalgo once again highlighted the need to face the importance and dangers of land titling as an end in itself.

“Rio de Janeiro has a very high incidence of untitled land, which can be a risk factor for vulnerable populations… However, it is essential to think carefully about titling… The titling of some locations will lead to harassment by the real estate market, an increase in the cost of living, and the removal of residents from that location… It is necessary to reflect critically on the model instituted for land titling at the federal level in recent years. We had a model that provided for development, recognizing social aspects that were also involved in land titling. Now we have a law that allows titling to be limited simply to the delivery of a land title to each resident.” — Tarcyla Fidalgo

Still on the dangers of this process, Fidalgo pointed out another provision amended by the Mayor’s Office that could have negative consequences, especially for favelas.

“A specific alteration by the Executive Branch in its amendments to the Master Plan is the unrestricted possibility of regrouping land in cases of land titling of specific interest… The possibility of joining lots and plots of lands is an important measure for titling, but this permission without any delimitation is absolutely dangerous.” — Tarcyla Fidalgo

Fidalgo then mentioned the example of Vidigal, a ‘trendy’ favela in Rio’s South Zone which, due to real estate speculation, could see this mechanism used to evict residents instead of guaranteeing the right to housing. She went on to call for the Community Land Trust to be reincorporated into the Master Plan as a way to prevent these traps and guarantee residents’ right to stay. She argued that the CLT helps protect communities from speculative real estate processes that may intensify following land titling.

Another important mechanism for the right to housing is combining the process of Compulsory Subdivision, Construction, or Use (PEUC) with that of Seizure of Abandoned Properties. According to Fidalgo, combining these instruments is very important to ensure the social use of abandoned properties, especially in downtown Rio. City Hall has criticized the two mechanisms claiming there is no funding available for the necessary renovations for buildings seized by public authorities. Fidalgo was applauded by those sitting in the galleries when she countered these claims arguing that money could come from charging the Onerous Grant that City Hall is exempting real estate developers from paying in the first five years of the Master Plan period. The strategic use of these instruments, specifically designed for the needs of each location, could be decisive in guaranteeing the right to housing in the city.

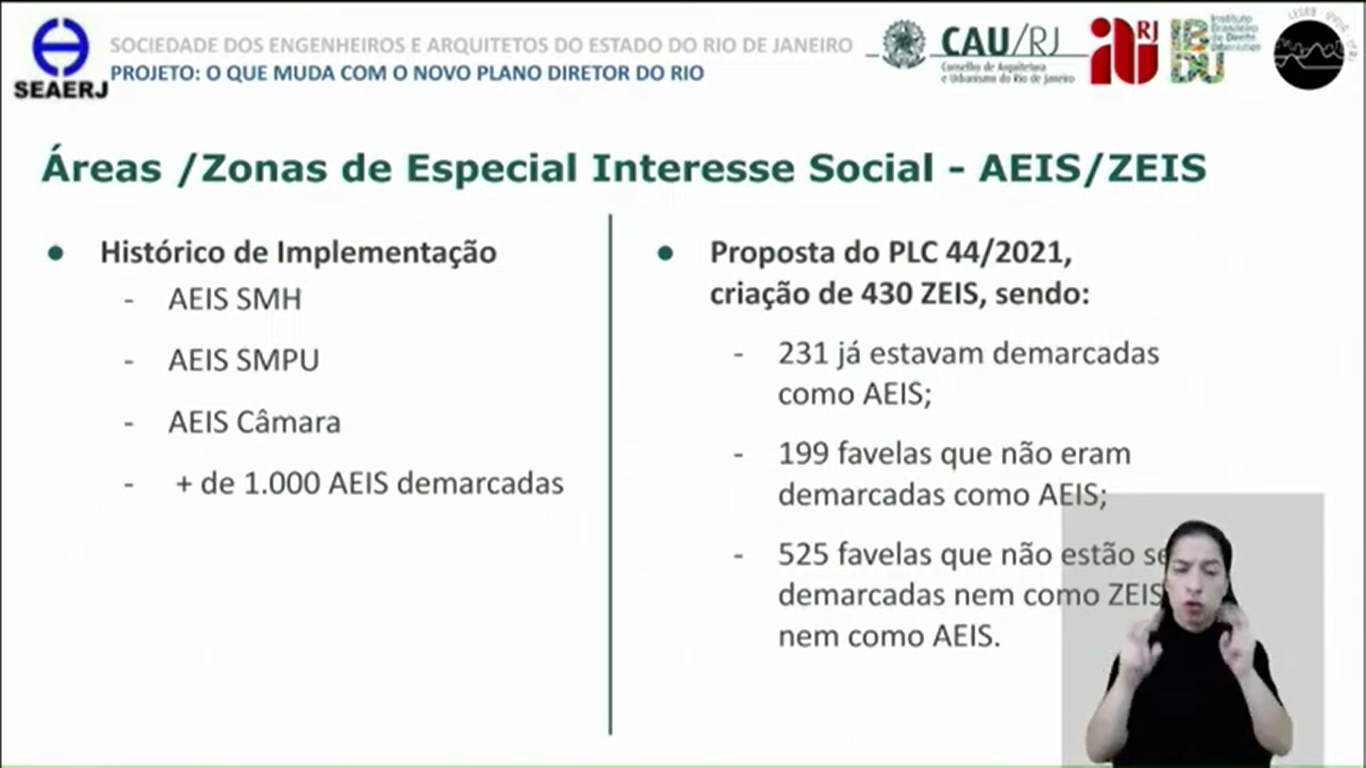

After Fidalgo, Marcela Abla took the floor again quoting the law to address the topic of Areas of Special Social Interest (AEIS) and Zones of Special Social Interest (ZEIS), “established to recognize the right to the city of low-income communities and enable social housing solutions.” There are currently over 1,000 AEIS demarcated by the legislative or executive branches in Rio, some in territories that are also demarcated as ZEIS, as is the case in 231 areas. However, according to the study presented by Abla, even with both legal provisions and their various means of organizing demarcations, there are still 525 favelas that have not been designated AEIS or ZEIS status, around half the favelas in the city.

Several participants reinforced the need to apply the Onerous Grant as an urban policy instrument during the hearing, including Mauro Salinas from the Rio de Janeiro Federation of Neighborhood Associations and Rose Compans from the Architecture and Urbanism Council. Salinas was unsparing in his criticism of City Hall’s attitude: “It’s a new Master Plan to be assessed… These amendments should be sent back to City Hall. They shouldn’t even be considered by councilors!”

Adrian dos Santos from the Movement for the Fight for Neighborhoods, Villages, and Favelas and member of the João Candido Occupation and Luiz Gama Occupation in Central Rio saluted those in the galleries and recognized the history of grassroots action in guaranteeing the right to housing. He said that it is the people who create alternatives for the right to the city, but it is the role of public authorities to ensure there is a budget, regardless of the device chosen for this purpose.

Maria da Penha Macena, a Vila Autódromo resident and leader from the Popular Council and Evictions Museum, then gave a short talk during which she recalled that there is nothing in the Master Plan that aims to help implement, protect, or support community museums. She said it is necessary for funding to be allocated to housing policies and social housing and called for the CLT to be reincorporated into the Master Plan—a model she learned about in person during a trip to New York.

“The CLT needs to be brought back!… It’s an opportunity for City Hall to work together with communities in a way that brings civil society, government, and society together. The city of Rio claims to work together with communities, but it doesn’t. I experienced [this] in Vila Autódromo [during the forced evictions]: they said one thing in the media while something else took place in the community… I had the opportunity to go to New York and see communities that have implemented CLTs with huge success. I spent a week there getting to know these communities. I can say with authority that the CLT is a tool that has everything to do with Rio de Janeiro because it can function in different ways—it can be used with communities that have been around for awhile, like our favelas and urban peripheries, but it can also be used for new housing projects… If we live in a democracy, as we claim to, the CLT will return to the Master Plan.” — Maria da Penha Macena

Mariana Trotta, a UFRJ professor and coordinator of the university’s Luísa Mahin Nucleus for Popular Legal Advice, works to guarantee the city is built in the interest of the majority.

“May the fundamental principle established in the 1988 Constitution—that housing is a social right—be realized. In Rio de Janeiro, we see many unused or underused properties, both public and private, that do not fulfill a social function. Data show there are over 800 such properties. We need an effective policy for these properties, mapping them while also having mechanisms like those proposed in the Master Plan, such as the Seizure [of Abandoned Properties]. Many of these properties have debts with the City and it is essential that we have the possibility of actioning this device, which allows the seizure of such properties for social housing… the priority is social housing but also that community housing associations can have the concession to use these properties.” — Mariana Trotta

She also raised two other issues that make residents of occupations and favelas vulnerable: the absence of a social housing policy in Central Rio and the possibility of temporarily placing evicted families on social rent. The municipal decree that establishes the social rent covers cases of state emergency, but not forced evictions. Evicted families are often left without housing options.

Next, Raphael Pazos, founder of the Rio de Janeiro Cycling Safety Commission (CSC-RJ), and Vivane Zampieri, founder of Bike on Track and member of CSC-RJ, argued emphatically for the need to see bike lanes as a public policy, including as income generation for the working classes. Pazos mentioned that this clean mode of transport became even more popular during the pandemic. Both argued that the bike lane expansion plan launched in March, CicloRio, be integrated in the Master Plan. For Zampieri, bikes are “an inclusive and democratic instrument—many people here have difficulty paying for public transport and end up using an active mode of transportation: foot or bike.”

Elizabeth Alves Bezerra from the Rio Articulation for Socio-Environmental Justice and SOS Vargens Movement spoke, receiving much support from the galleries. She strongly criticized City Hall’s proposed changes to the Master Plan, the greed of the real estate sector, and the lack of housing and environmental policies for the city. She denounced the hypocrisy of the City presenting itself as a sustainable administration in international forums and the media, while instituting the destruction of the Vargens ecosystem, part of what is called the Pantanal Carioca or Rio’s Urban Wetlands, an area that is fundamental in the fight against climate change in the city.

“I’m not bringing proposals, I believe that all the proposals that could be made have been made… We, the people of Rio de Janeiro, hope this Council puts a stop to these proposals made by City Hall… In practice, City Hall is the enemy of the environment, it places entire populations at risk. Why was the CLT not included in the Master Plan draft bill? Land regularization does not interest the City. For the City, land is a commodity!… Social disorganization in Rio is in the interest of the City… The City has committed a federal crime for the second time, via a decree which reduces the Vargens Full Preservation Area… The area has a social function, even more so than environmental preservation. City Hall is condemning the remaining Jacarepaguá Lagoon Basin to extinction. That area is currently the largest area of carbon sequestration in the city. What does the end of it mean for Rio de Janeiro?” — Elizabeth Alves Bezerra

Elizabeth Alvez Bezerra also asked what the City had planned in its amendments to combat flooding. She said:

“In Vargens alone, flooding will mean the displacement of 15,000 to 20,000 climatically vulnerable families… You hold the pen in your hands. You only have two paths to follow: to go down in history as being responsible for ecocide or as builders of this city.”

Luciane Wanderly de Jong from the São Cristóvão Neighborhood Association remarked: “This city’s potential has always been thrown in the trash.” And William Evangelista Freire from the Zumbi Occupation emphasized that occupations are a solution to the lack of housing. He said with pride that the children in his occupation go to school. However, lack of government support and structural damages threatening the integrity of the building mean the families living there are at risk.

“Lately we have been treated like nobodies. Except that these nobodies are people who vote, people that need to work, and that are in an occupation because of a lack of employment. Many people don’t have dignified housing. In Zumbi, there are 100 children, 99% are in school. They study because we ask the families to enroll their child in school when they arrive at the occupation… Zumbi is in danger of collapsing, but it’s easier to throw us out on the street than offer us something better… There are over 120 occupations in Central Rio and there’s an eviction order on its way for everyone…. We are people! We want housing!” — William Evangelista Freire

Paulo Roberto da Silva Machado, a resident and president of the Trapicheiros Neighborhood Association, in Tijuca, spoke about the process of real estate speculation and eviction his community has faced. He reaffirmed the importance he believes the CLT has for areas which suffer this threat, also citing his personal experience visiting the CLT in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

“The CLT has had a huge significance in our lives. We’ve had contact with it since 2019. We had the opportunity to get to know the CLT up close in Puerto Rico and I saw what the CLT can give favela areas. The Caño Martin Pena community is in San Juan, capital of Puerto Rico, and I saw how civil society, communities, and government can work together to drive life forward.” — Paulo Roberto da Silva Machado

Emília Sousa, resident of the Horto community and Popular Council leader, spoke again briefly in support of Maria da Penha Macena’s talk. “I reinforce Penha’s words on the issue of inclusion regarding culture, on community museums which speak about memory, preserving the history of citizens who have contributed to this city… for their inclusion as a mechanism in the Master Plan… I ask for the CLT’s return as an essential instrument for land titling of communities and favelas.”

The hearing closed with talks from former Secretary Washington Fajardo, Councilor Thais Ferreira, and City Hall representatives Undersecretary Thiago Ramos Dias and Macro Planning Manager Valéria Hazen who reiterated points made in the April 5 hearing. According to Dias, who once again did not respond directly to criticisms made throughout the long hearing, City Hall’s work has been done and it is up to the Council to “bring the people’s voice into the Bill’s text,” as if these are conflicting proposals and interests. As such, the public continues not knowing the real motivations behind the CLT’s removal from the Master Plan.

“From the legislative process perspective, the City Government’s work ends with the presentation of its amendments… The view posed by the government is made up of diverse voices and opinions taken to its democratically elected leader [Eduardo Paes], who has the exclusive prerogative of translating this message in the bill, which is now being analyzed in these Chambers. It is and continues to be the view of the City Government leader and the whole of City Hall as a result. This is the final view. Will it be translated into law? I don’t know, that’s why this House exists, to moderate these views and bring the people’s voice into the Bill’s text… it can still override vetoes in exercising its function.” — Thiago Ramos Dias, Executive Undersecretary at the Municipal Secretariat for Economic Development, Innovation, and Streamlining (SMDEIS)

Following the public hearings about urban policy mechanisms, the next weeks will see public hearings about different regions of the city. These will be tasked with discussing developments in the amendments by City Hall in the Master Plan about those regions in accordance with each city Planning Area (AP). The regional discussions began on April 19 at 9:30am at City Council, starting with AP1 which covers Rio de Janeiro’s Central Region.

Watch the Recording of the Public Hearing on April 12 Here.

*RioOnWatch and the Favela Community Land Trust (Favela-CLT) are both initiatives by the non-profit organization Catalytic Communities (CatComm)