On Saturday, June 17, Vila Autódromo in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone hosted the launch of the Climate Memory of the Favelas Exhibition, organized by community museum members of the Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) and partners. The event was a culmination of memory circles held by five community museums earlier this year: the Maré Museum, Sankofa Museum in Rocinha, Historic Orientation and Research Nucleus of Santa Cruz (NOPH) in Antares, Favela Museum (MUF) in Pavão-Pavãozinho/Cantagalo, and the Vidigal Memories Nucleus. The voluminous climate memory narratives, as told by residents themselves, resulted in the exhibition.

An Exhibition in an Open Air Museum

The Vila Autódromo favela used to occupy a much larger area on the edge of the Jacarepaguá Lagoon and Rio’s former racetrack. With a history marked by housing rights battles and resistance, Vila Autódromo is now home to the Evictions Museum—a community museum founded in 2016 following the forced eviction of hundreds of families in the period leading up to the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics. Today, only a few houses and the São José Operário church remain. The Evictions Museum was founded there in 2016 with the mission of keeping alive the memory of communities threatened with eviction.

It is thus not by chance that the Evictions Museum was selected as the location to launch the Favela Climate Memory exhibition. The launch event featured a variety of activities encouraging reflection, discussion, and celebration of favela resistance experiences. On arrival, visitors could view five banners with a brief summary of the climate memory circles carried out by five favela museums.

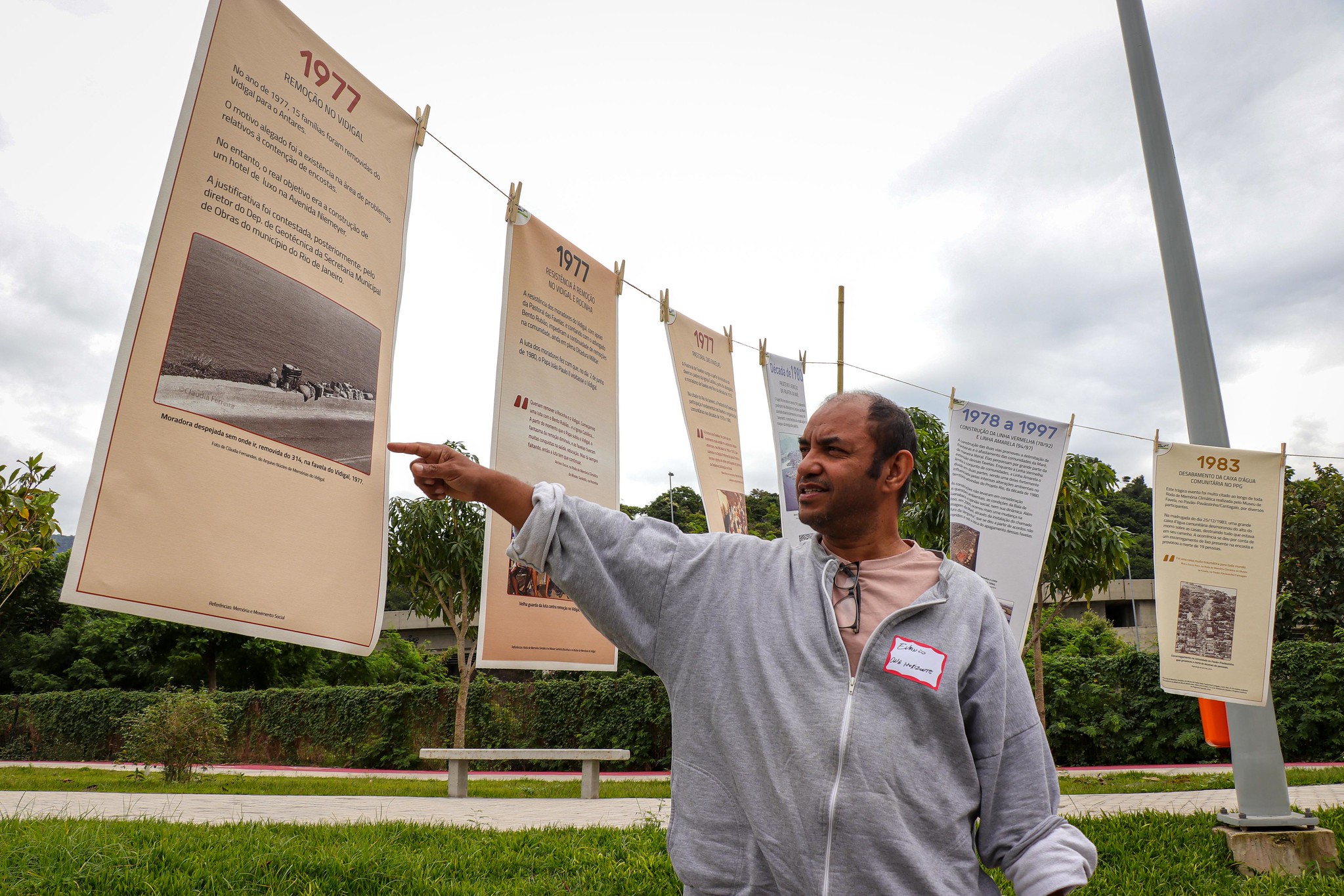

The outdoor part of the exhibition also featured an eye-catching and extensive timeline in circular format presenting significant points in the histories of the favelas covered by the exhibition. The timeline was based on notable events mentioned during the memory circles.

Evânio de Paula, a Vidigal resident and president of the Horizon Sporting and Cultural Association, felt a real connection in this space. He was looking at a panel on the timeline with a photo of an eviction in Vidigal, supposedly because of problems related to stabilizing the hill slopes; he said he was seven years old when this occurred in 1977. In his talk, he remembered the eviction resistance strategies he experienced in childhood.

“At that time, I was seven years old… and to avoid eviction, Dona Heneida Brasil, a community leader… took everyone from Rua Almirante Tamandaré to Avenida Niemeyer. Children stayed in front of [the Military Police’s] shock battalion to prevent police coming to take away families. A group of students stayed at the entrance to Vidigal. Then came women and men with the Brazilian flag, singing the national anthem.” — Evânio de Paula

The residents association and Favelas Pastoral Committee arranged for Pope John Paul II to visit Vidigal in 1980. This led to a reduction in the onslaught of attempts to evict residents from favelas in the South Zone, particularly Vidigal and Rocinha.

In the middle of the amphitheater—a legacy of Vila Autódromo residents’ fight—and with the timeline surrounding it, the exhibition included an art installation titled “Well of Memories” by Evânia de Paula, a visual artist from Vidigal. The installation provided a space for sharing local memories and stories and where people could look at old photos with captions describing memories.

Visitors gathered at the São José Operário Church for the start of the event to get together and settle in for the exhibition opening. Gisele Moura, coordinator of the Sustainable Favela Network’s managing team, emphasized the importance of initiatives that value favela memories, especially regarding environmental issues, since favelas are the areas most affected by climate change in Rio de Janeiro.

“The project culminating in the exhibition today was first thought of collectively in 2020 by the SFN’s Culture and Memory Working Group, that had the idea of considering climate memory based on the experiences, memories, and conversations among people in those locations… [and this is how] the idea of climate memory circles in the favelas was conceived.” — Gisele Moura

Four mini-documentaries produced about the memory circles were screened during the exhibition opening, 27 minutes in total, now available with English subtitles (see just below). The films document resident reflections on climate change, communities’ relationship with nature, how climate relates to housing rights, and what solutions communities have developed to address such issues.

Mini-doc #1: What does climate change mean to you?

Mini-doc #2: How was your favela’s settlement related to nature and climate?

Mini-doc #3: How does climate relate to the right to housing?

Mini-doc #4: What approaches did your favela develop to respond to the challenges imposed by nature and climate?

Climate Memory of the Favelas: Voices of Maré, Rocinha, Antares, PPG, and Vidigal

After the film screening, representatives of the community museums that hosted the five climate memory circles were invited to comment on the process of how the circles were conceived and organized and also the final result, presented in the video and exhibition.

Antônio Firmino from the Sankofa Museum in Rocinha emphasized the issue of environmental racism. He stated that the collective work realized through the memory circles should become public policy to benefit favelas.

“[The discussion circles] leave a huge challenge, that is to bring up the issues we all face because of environmental racism… And since we are in a pre-election period, [it is important] we bring all this collective work in our favor, because we depend on public policies to improve certain issues in the favelas.” — Antônio Firmino, Sankofa Museum

Leonardo Ribeiro, born and raised in Antares, Santa Cruz, said that taking part in the discussion circles had been fascinating. He brought a historical angle that runs through the entire exhibition and spoke of how his community is linked with all the other favelas where evictions took place.

“Antares has a strong connection with all the communities where the circles were held. Over in Antares, we have families evicted from Maré, mainly, and also from Vidigal, Rocinha, and Pavão-Pavãozinho… There are many families that couldn’t afford to stay in City of God and came to Antares because life was cheaper there. This movement of going to the circles and learning, even to a community 80 kilometers from downtown Rio de Janeiro, this act of coming to our origin is very difficult. Going to other communities, understanding how they persevered after evictions and how Antares developed was incredible.” — Leonardo Ribeiro, Antares, Santa Cruz

Bruno Almeida, coordinator of the Historic Orientation and Research Nucleus of Santa Cruz (NOPH), commented that the historical silencing and erasure of favela narratives is intentional.

“Usually when you talk about the past in an urban periphery neighborhood, we don’t include favelas as part of the neighborhood’s history… When we talk about the history of Santa Cruz, we aren’t only talking about official history, like the imperial neighborhood… but we are in this process, together with the Sustainable Favela Network, of including favela histories in this narrative because occupying the geographic space we live in is also part of the neighborhood’s history.” — Bruno Almeida, NOPH

Márcia Souza, a Cantagalo resident and director of the Favela Museum (MUF), pointed out that taking part in the discussion circles was very significant.

“Leaving our communities to get to know other favelas and other people that do the same things we do—the names are different, the places are different, but it’s the same everywhere… I found out that we are all connected by the same history, by the same hardship, with different points of view, but that if you stop to take a breath, it’s the same everywhere.” — Márcia Souza, MUF

Bárbara Nascimento from the Vidigal Memories Nucleus said the move to discuss favelas being made by those in the communities themselves is very interesting.

“The initiative to bring favelas together to discuss a very common theme is so important. And, although each area has its own history, we have so much in common, because many favelas were removed or had attempts at removal, and the justification used was the climate, rains, and landslides. Our histories are similar, so nothing could be more fitting than us getting together to discuss strategies. It’s great knowing that there are favela residents discussing the favelas, us talking about our own locations.” — Bárbara Nascimento

After many powerful and necessary talks on the exhibition launch, Maria da Penha, a community leader from Vila Autódromo and member of the Evictions Museum, made her contribution. She spoke on the right to housing, her story of resistance, and how she fought not to be evicted from her community.

“I understood what housing rights were, these much discussed rights, so pretty on paper, but that don’t work for us poor people if we do not demand them… We are from favelas and need to be conscious of that… society is always telling us that we can’t live here, that we have to be ashamed [of where we live]. It is exactly the opposite: each day that goes by, I am happier to be able to be here in the garage of my house, in my location… it isn’t easy to go through evictions, it’s painful, it’s cruel. No one builds a house thinking they’ll see it be demolished.” — Maria da Penha

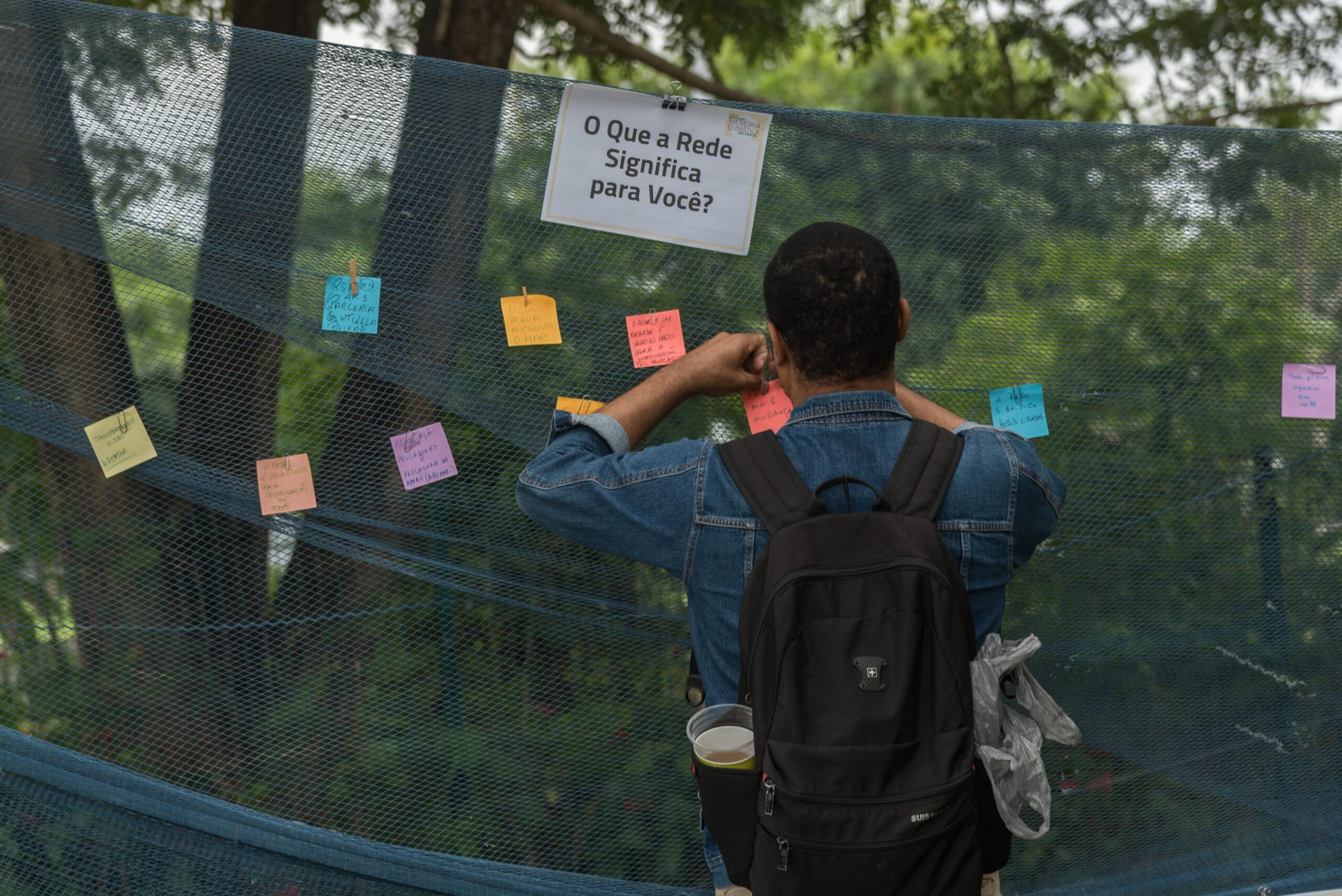

After a morning full of reflections, the lunch break provided another opportunity for attendees to interact and get involved with other aspects of the exhibition. These included an interactive map where people could put memories on locations and take part in an affective mapping experience, and a fishing net from Complexo da Maré where visitors could hang messages and reflections based on the question: “What does the net mean to you?”

Another much anticipated moment was the “Penha” short play. Performed by actors Nathalia Macena and Fernanda dos Santos from the Por um Triz collective, the hard-hitting play enacted times of anguish and hope for Maria da Penha—Nathalia’s mother—in the fight against evictions in Vila Autódromo. After the performance there was a discussion circle that concluded with those present sharing their reflections on themes covered during the event.

The launch of the Favela Climate Memory exhibition is the closing of a collective work cycle organized by favela museum members of the Sustainable Favela Network. It also marks the beginning of a new cycle of history being told by people in the favelas. A better understanding of history and memory stimulates community pride, a feeling of belonging, mobilization, and self-organization in the fight for rights and public policies that make resident’s lives safer and build favelas resilient to climate change.

Don’t miss the video by Luiza de Andrade (or click here to watch on YouTube):

Don’t miss the photo album by Alexandre Cerqueira (or click here to view on Flickr):

About the author: Bárbara Dias was born and raised in Bangu, in Rio’s West Zone. She has a degree in Biological Sciences, a master’s in Environmental Education, and has been a public school teacher since 2006. She is a photojournalist and also works with documentary photography. She is a popular communicator for Núcleo Piratininga de Comunicação (NPC) and co-founder of Coletivo Fotoguerrilha.

*The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) and RioOnWatch are both projects of Catalytic Communities.