Clique aqui para Português

On June 17, 2023, Rio de Janeiro’s Sustainable Favela Network (SFN)* launched its Favela Climate Memory Exhibition, the culmination of five day-long climate memory circles held by favela community museums between January and March. This series of articles explores the dynamics of each memory circle which makes up the exhibition, with this article introducing the fifth discussion circle, held on March 12 by the Vidigal Memories Nucleus. Developed by the SFN’s Culture and Memory Working Group, the project was realized by community museums, technical allies, and community organizers from favelas across Greater Rio.

The Sustainable Favela Network’s Climate Memory Circles are community events aimed at recovering and recording the memories and stories of long-time residents of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas in relation to the environment so as to envision ways to prepare for climate changes to come. Though still rarely discussed, the memory circles showed that climate change is very much present in the daily lives and concerns of favela residents.

Each memory circle event took place over the course of a day, with residents invited by the museums to take part in a series of discussions designed to focus on and dig deeper into the climate change theme. Residents shared their views and experiences of climate change, recovered memories about the settling of their communities and the relationship of this settlement period with the surrounding environment, discussed the relationship between climate impacts and housing rights, and explored solutions and organizing by residents, highlighting the mistaken priorities of the State, which tends to see forced evictions as the solution.

On March 12, 50 people gathered at the headquarters of the All in the Fight Institute for the last Climate Memory Circle, organized by the Vidigal Memories Nucleus, in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro. Many residents attended including a centenarian matriarch and representatives of Vidigal community organizations including the Vila do Vidigal Residents Association (AMVV), Network Community, Nós do Morro theater group, Stop Killing Us (PdNM), NGO Horizon, SER Alzira Project, ART of Color Vidigal Project, and Vidigal in the Social, in addition to partners from external organizations.

What Is Climate Change?

At the opening of the event, Bárbara Nascimento, 44, from the Vidigal Memories Nucleus, introduced the first circle’s guiding question: “What is climate change?” She went on to say that “the history of Vidigal is completely tied up with the environmental issue.” In the 1970s, public authorities tried to remove the part of Vidigal known as 314 claiming there was imminent risk of landslide. The same tactic is being repeated today in the Jaqueira area of Vidigal—a recurrent topic throughout the discussion circle.

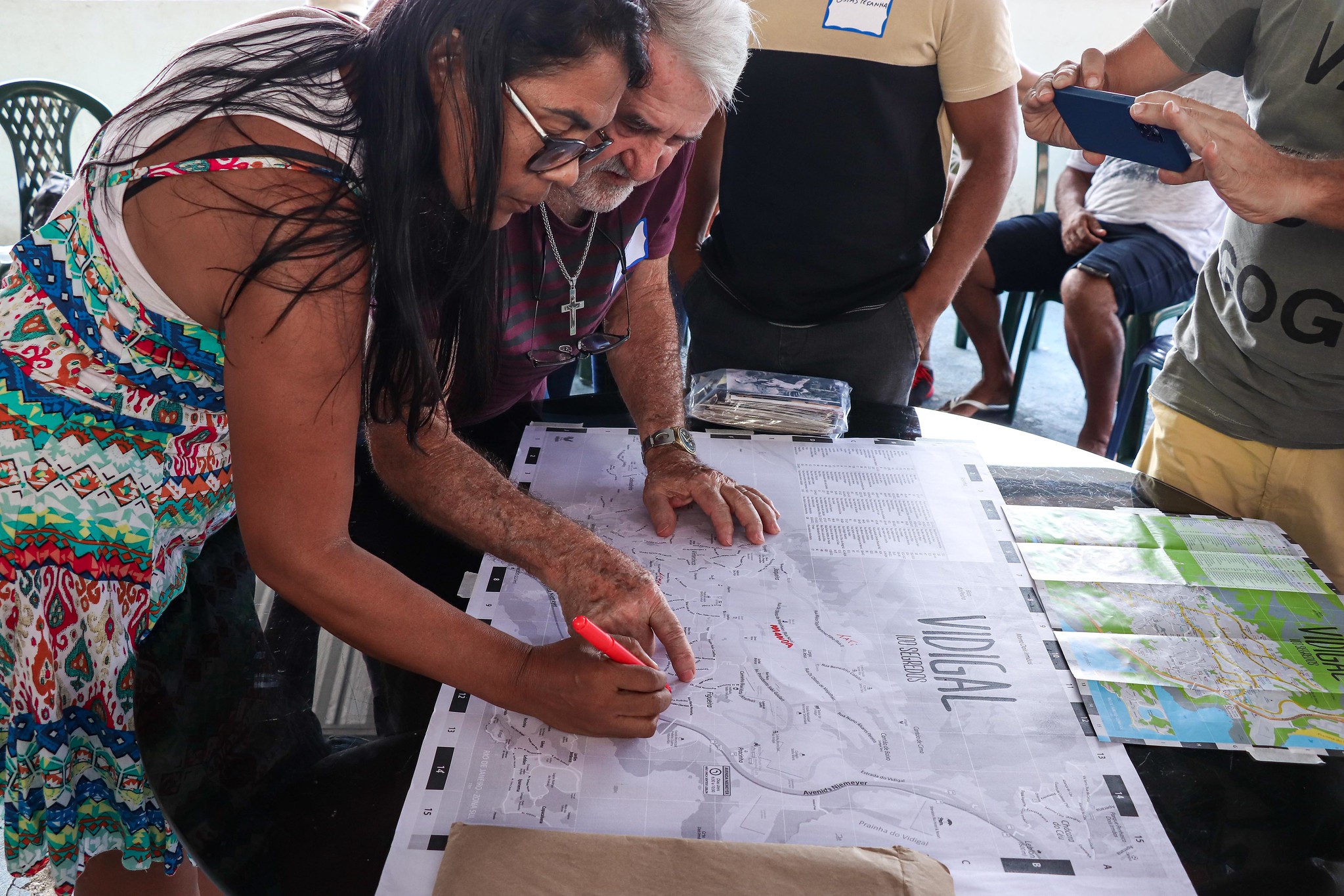

Residents were invited to approach the Map of Vidigal made by André Koller, a German who has lived in Vidigal for 15 years. The aim was to locate the streets where they live and write their names. The favela was [officially] on the map.

“It’s interesting to look [for your street] on the map, because for a long time the favela wasn’t on the map… As for the question of space in the favela, Vidigal has a particular feature: our streets honor the people who have played a role in our history. For example, ‘o Arvrão’, which is Mr. Armando. We honor our community personalities in life.” — Bárbara Nascimento

Kicking off the first discussion topic about what climate change is, Nascimento pondered:

“We sometimes think this subject is very distant, when in fact it is not. When in fact, the issue of climate change has a direct impact on the favela, including what many call environmental racism because when tragedy strikes with the rains, it is the favela population that suffers most with the consequences—with landslides, floods.” — Bárbara Nascimento

Reinforcing Nascimento’s point, Osias Pinto Peçanha, 56, a former resident, linked climate change to consumerism. He also exposed the fact that favelas are the areas which experience the greatest impacts and that this has been happening for years, confirming a situation of climate injustice.

“We [human beings] are compulsive consumers. Where does our garbage go?… The favelas have always been impacted [by climate change], the worst effects are in the favelas… Not much has changed. It keeps happening. Landslides, floods. Climate change, caused by overconsumption, has more impact in the favelas.” — Osias Pinto Peçanha

Armando Almeida Lima, a favela resident for over 60 years, and former president of Vidigal’s residents association, is a historical reference in the fight against forced evictions during Brazil’s military dictatorship. He recalled Vidigal in the 1950s and 1960s and shared his view that deforestation increases due to the absence of efficient housing policies.

“I arrived in 1959. The community here was a forest. We breathed pure mountain air. Time went by, people needed homes. From my window I can see it. What used to be forest forest became houses. People needed somewhere to live! People need a place to live! Where will my children live? They can’t live in Leblon [wealthy neighborhood next to Vidigal]. So it’s got to be here. I’ll tear one more tree down. That’s one less tree. One less [source of] fresh air to breathe.” — Armando Almeida Lima

Following Seu Armando’s talk, the exchange came and went but focused mainly, for the rest of the day, on the issue of housing rights—a tremendous concern in the favela with the highest market real estate values in Rio de Janeiro. Housing rights remained the central theme of the discussion, despite originally being intended as a discussion topic later in the day.

Antônio Paiva, 59, is a resident of Jaqueira whose house was seriously damaged by the rains of 2019. Families from Jaqueira filed a lawsuit for City Hall to fairly compensate them. Their houses were condemned by the Civil Defense. Paiva reported that the amount of compensation offered by the City is negligible compared to the high cost of living in Vidigal.

“We’re at war in the courts regarding the removal of our houses in Jaqueira. City Hall offered R$11,000 [US$ 2,232] for some houses, thinking they were paying too much. Except that it was reported in the news that a square meter in Vidigal costs R$19,000 [US$ 3,854]. They offered R$1,800 [US$ 365] per square meter. Once again the courts came to measure our community, in our homes. Only they are so smart that they managed to play us off against each other. I don’t know how they did it. All I know is that [now] residents aren’t talking to each other.” — Antônio Paiva

Amanda dos Santos Francisco, 35, is a resident who was born and raised in Vidigal, and whose family migrated from Bahia in Northeast Brazil decades ago. She opined about what she called a “veiled eviction attempt”—a strategy employed by certain administrations.

Evânia de Paula Muniz, 56, is a visual artist born and raised in Vidigal involved in various projects that value environmental sustainability. She argued that blaming residents for the growth of favelas is unfair, because, without a housing policy, they have no other option.

“The favela grew a lot vertically and concreted the land. So what is likely to happen? Urban heat waves… Favelas are created out of necessity. They aren’t guilty of disorderly occupation… people don’t occupy land because they want to, but out of need… Favelas will continue to grow because there’s no investment on accessible housing in the city. For poor workers, the only option is to live in favelas or occupy abandoned public buildings.” — Evânia de Paula Muniz

Júlia Chaves Giglio, 35, from the All in the Fight Institute, highlighted another consequence of the absence of housing policy: lack of water supply. Giglio described how she can see what’s left of a river from her home in Atalho, now turned into a sewer. She questioned the government’s lack of planning and its potential to reinforce climate injustice.

“From what I’ve been learning, we could mention the lack of water on Rua 3, which also has to do with climate change. So many houses are being built that the water supply is no longer enough… I can still see the remains of the river from a window at home. I say it’s a waterfall, but it doesn’t smell like a waterfall.” — Júlia Chaves Giglio

Aristides Peixoto Filho, 65, Giglio’s neighbor and a resident for 40 years, referred to the degradation of the area and residents’ responsibility in this process: “It’s not just the government that has to do things. We have an obligation to take care of our home, the place where we live.” He said that people lack education at all levels, including with regard to the environment, and referred to garbage being dumped in the streets, alleys, and hillsides. It is important to note, however, that the main responsibility lies with the authorities and inefficient policies for solid waste management and sanitary sewerage in favelas.

How Did the Occupation of the Favela Happen and What is the Area’s Relationship With the Climate and Nature?

Rita de Cassia Machado, 58, a resident of the 314 area in Vidigal for 44 years, shared memories of the favela and recounted the processes of change she has witnessed in Vidigal.

“I remember when my family came to live here, the houses were spaced out, everyone had a backyard. You could see the sea from your backyard and smell the sea air… There were houses with fences. Wind. A direct view of the sea… Vidigal grew a lot like everywhere else, but it grew much more than the formal city due to the need for housing, the impoverishment of the population… Due to this impoverishment, population growth in the favela happened without proper support, without the proper infrastructure of public services, garbage collection, basic sanitation, and water supply… You have a one-story house, then the family grows and builds another story… I understand that this all has to do with the climate issue. Before, we felt fresh air inside the house. Today you have to go out, put your face outside to try to feel the sea breeze. The number of houses that turned into tiny boxes… We didn’t live in a loft in the old days, [but] that’s how it feels now.” — Rita de Cassia Machado

She went on to say that in the late 1970s and 1980s, the AMVV had legitimacy given by residents and legality negotiated with the authorities to prevent construction in risk areas. According to her, when building standards were not respected, irregular buildings were demolished by the Association, for the collective benefit of the favela.

“I remember a house there in Pedrinha, the first house built on top of the rock. Residents filed a complaint, the association tore it down. A house was built glued to the stone. At first, no one knew whose house it was, after it was known, the association maintained its stance.” — Rita de Cassia Machado

Rita de Cassia Machado worked on two historic land titling projects in the favela: Each Family a Plot of Land, under the Brizola administration in the 1980s, or “each family a default,” as Armando Almeida Lima put it; and Land Regularization in the 2000s. She spoke of her amazement at seeing the overwhelming increase in housing in the time between one project and the other. She believes that, without housing policies in the favelas, there will not be the infrastructure capable of supporting the growth of these communities and preventing tragedies arising from climate change.

Going around the climate memory circle, Antônio Carlos de Aleluia, 71, from one of the community’s oldest families, began his talk by sharing a little of what his grandmother, Alzira Zulmira de Aleluia, told him about her background and coming to the favela.

“My grandmother Alzira de Alleluia was the daughter of slaves and escaped [slavery] with the Free Womb Law [enacted in 1871 which granted freedom to all children born to enslaved people]. The first people to come here to Vidigal arrived from Mozambique. They came on the slave ship, but they knew how to read and write. [The abducted Africans] were thrown into Praça XV and they’d run deep into the woods and all the way to Minas Gerais on foot because they knew how to read and write. When they got there, there was no notary, [they went to] the Catholic Church… [and said] we are free men. And they said, you have to have a last name. As it was a Hallelujah Saturday [Aleluia in Portuguese], the priest gave them this name. Thus began the Aleluias family saga (applause). So, this family name Aleluia grew here with the [other] families.” — Antônio Carlos de Aleluia

Seu Aleluia, as he is known, also spoke about the centrality of the Almirante Tamandaré School in Vidigal around the 1960s. In addition to being a great school with dedicated teachers, it served as a shelter for residents in situations of environmental risk on various occasions. He told of the 1957 flood when he took shelter at the Almirante Tamandaré School with his family.

“I was the first student to go to Tamandaré, which opened in 1956. In my [time], you could start at the age of 7. I was one of the first to go there. The teachers were really caring… I finished and was the first student to attend the state high school. I wanted to compete with the students from Santo Inácio and Santo Agostinho [prestigious schools in the formal city]. Tamandaré was a strong school, very demanding. I went to study in Urca, where I suffered racism for the first time… of the young people there, one was the son of General Castelo Branco, who created the dictatorship… Urca is the most elitist place in Rio de Janeiro… When my mother got there, she asked ‘what happened?’ And the school principal replied, ‘we have the son of president Castelo Branco here. And he’s the only Black child here.’ She replied ‘my son got in here through a competitive exam, he’s the only Black child. And he’s staying.’ So, the principal started giving me a stipend from the school fund, clothes, canteen money… I got in to the Fluminense Federal University. I was the first student from Vidigal to attend a federal university. And then I chose the profession I found interesting, which was engineering… Today I’m a professor at UFF, I always get [to the university] and say that I’m from Vidigal, born and raised in a shack… Do you remember the rains in 1952? We stayed at the Tamandaré School during the flood that swept through the whole of Vidigal. I was sheltered there at the school… that place was very good to me.” — Antônio Carlos de Aleluia

Continuing to talk about climate memory, Seu Aleluia emphasized the place of residents murdered by environmental racism, inefficient public policies, and government neglect. It is necessary to remember the dead when talking about climate memory in the favelas, to try to prevent the same tragedies from happening again.

“Do you remember Mr. Vitor’s rock? They put a support brace on that rock that was going to cause disaster… It was an atomic bomb… [the brace] was made by the residents’ association… Now we have another atomic bomb. There has been a lot of deforestation in Vidigal, so the water flows down violently [now]… The stone that came down toward our house killed Vandinha. To this day, her body is there, it couldn’t be removed because everything was crushed.” — Antônio Carlos de Aleluia

Then, Bárbara Nascimento, both born and raised in Vidigal and also a researcher of the favela’s formation and local memory, spoke a little about the history of the area.

“The name Vidigal comes from a major, Major Miguel Nunes Vidigal, who incidentally got these lands here as a gift from the Catholic Church for curbing demonstrations by Black people. Vidigal is a favela with a Black population. The first two residents of Vidigal were the major and Charles Ariston, who founded the Anglo School, which is Stella Maristoday. Both were hygienists… But here we are, and we are resisting… According to official data, they say that Vidigal started being occupied in 1940. There is nothing to prove that… We think it was much further back. If today we continue to talk about the possibility of eviction in Jaqueira, 45 years ago, Mr. Armando was a leader against this eviction [which is still threatened today].” — Bárbara Nascimento

As you go up Vidigal’s main road—Avenida Presidente João Goulart, formerly Estrada do Tambá—there’s the favela on one side and privately owned land on the other, a region known as “of the owners.” Real estate belonging to favela residents and private owners practically share the same space, up to the point where this distinction becomes confused. However, this is precisely why the border is constantly being reinforced by prejudice, which distances neighbors who live meters away from each other. It should be noted that the same type of discrimination can also be witnessed within the favela. Some residents of more upscale locations in Vidigal do not see themselves as favela residents and, therefore, make no effort to fight the same battles. And the authorities benefit from the lack of unity caused by internal divisions.

Osias Pinto Peçanha was born and raised in Vidigal and now lives in the Baixada Fluminense. Most of his family still live in Vidigal. He blamed the State for the lack of an effective environmental policy and shared that this almost killed his family and prompted his move from Vidigal.

“My grandmother bought one of those plots of land there. We belong to the discriminated IPTU [property tax] group… Listening to Mr. Aleluia speak, Mr. Armando, our griots, we need a book of these memories!… My house was hit by the flood on February 6, 2019. I was in Caxias teaching human rights. While I was teaching, my wife and daughter were being rescued through the window because… well, anyway. We moved, now we live in the Baixada. My brothers and my mother are still here. We are here all the time. I love this place. The State is responsible for the lack of public policies… There is no political will to solve the problem.” — Osias Pinto Peçanha

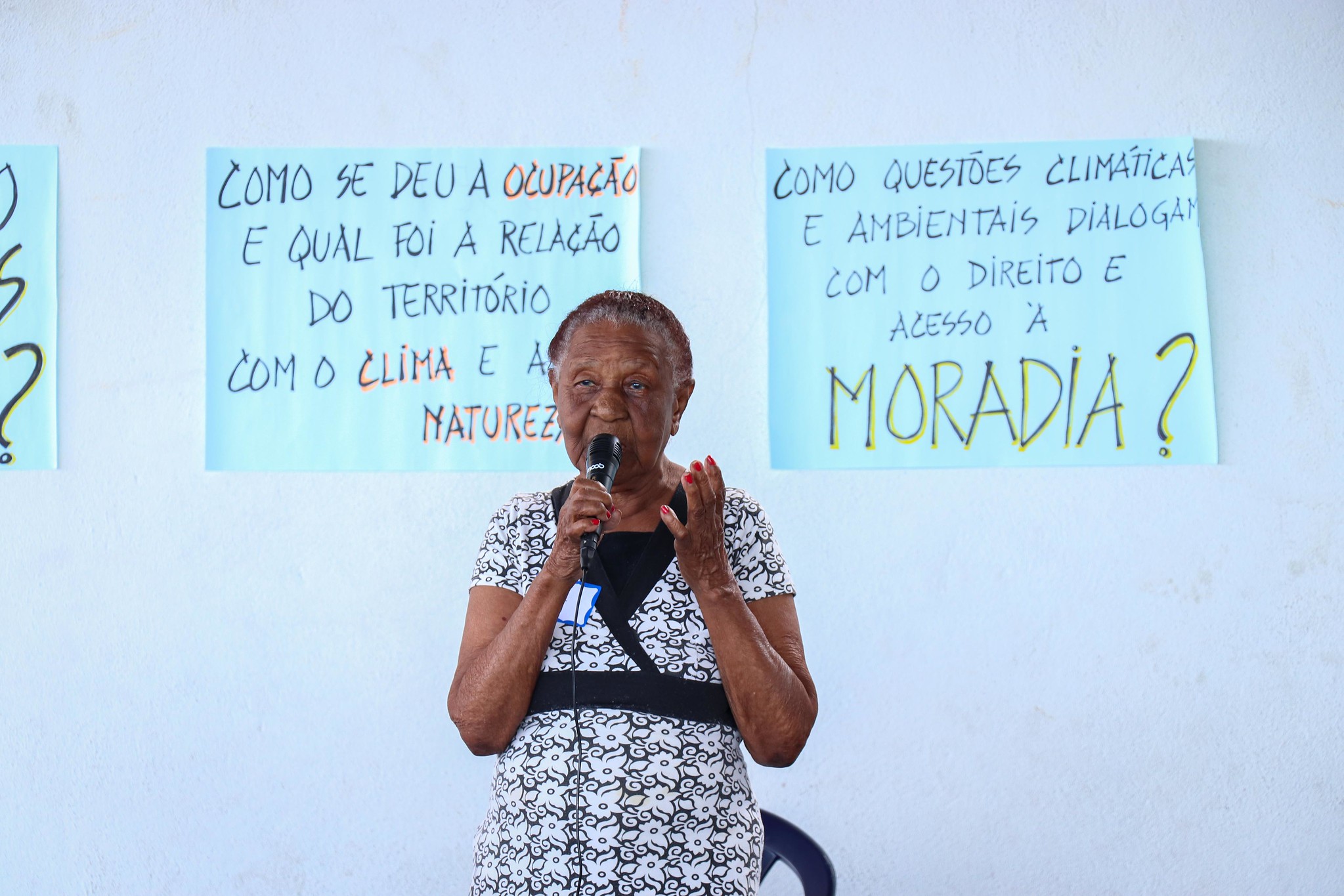

How do Climate and Environmental Issues Dialogue with Housing Rights and Access?

The day’s third guiding question—how do climate and environmental issues dialogue with housing rights and access?—was introduced, though these issues had been clearly present in the exchange thus far. The conversation therefore continued exploring this theme.

Resident Tatiana de Souza Moraes, 32, also recalled the 2019 flood, which hit the Jaqueira region hard. She told of the horrific night she had, witnessing the death of her neighbors. Every moment she thought it could be her and her children under the rubble.

“I was terrified in that moment because I really put myself in other people’s shoes. I lived in Jaqueira, on Rua 3. I could have been living in that spot when that happened. I could have been there with my kids. It was unreal. And it started in the early hours of the morning, I remember it to this day. I used to live in that building over there. I started to hear screams. People asking for help and I was desperate, looking out the window… I started shouting: ‘There’s a garage down there!’ We opened the garage and the people stayed there… At three o’clock in the morning, I went to sleep because I had work the next day. When I woke up at seven, I was very much in shock. I’d never witnessed such floods up close. There was a lady’s body on the ground.” — Tatiana de Souza Moraes

Rita de Cassia Machado continued to share stories of her neighbors surviving climate disasters and once again reinforced the role of the Almirante Tamandaré School, which has always represented a safe haven for the community. The school is one of the only public provisions present alongside residents during episodes of environmental racism.

“When the flood happened in 1996, I was an educator at the daycare center. We climbed up the hill to get people out so that the firefighters could go in… We dug with our hands to try to save people who were buried. We are only aware of the devastating effect of climate change when we are there. It was very difficult, Tamandaré once again sheltered the displaced… when it rains hard, the volume of water is so great there’s a waterspout. And we see a lot get washed away. In 314, the entire slope turns into a waterfall.” — Rita Machado

There was a common desire among residents at the circle to put political pressure on the authorities, which they see as responsible for deaths and destruction caused by extreme weather events in Vidigal, believing that public works could be carried out instead of evictions.

“People can say that housing has nothing to do with climate change. But it has everything to do with it! Because when water forges a path, there’s no fighting it. A rich man will build a structure on top and the water runs underneath it. The poor don’t think about where the water runs, only about what they can do at that moment. So where are our politicians? … We need to call Nós do Morro, the association, business owners, and make this movement happen, because it’s not just Jaqueira. There are evictions proposed across the whole state of Rio de Janeiro. And that will change our history.” — Mauro Ferreira da Silva

The lack of political will among those in power, bureaucracy, and the blame game between authorities only worsen the situation.

“Everything on Pedrinha, which goes up to Santinho, is very fragile. We have to create a movement to take this to City Hall, because this is urgent. They said that this land is always shifting… shifting land, with rocks! There are very high risk areas in the 25 [region of the community]. In Jaqueira we have loose material [on the slopes]… So we have to fight systematically for this. They made barriers down there at Niemeyer [avenue at the foot of Vidigal], I asked [Geo-Rio] why they don’t do the same up here. They said it’s more expensive, that it’s the responsibility of the [state] government.” — André Gosi

Memories of floods that caused tragedies in the favela took over the circle. Seu Aleluia and Mr. Armando shared memories of floods between 1950 and 1960. Others, including Bárbara Nascimento and Rita Machado, recalled those from 1988 and 1996. Those from 2015 and 2019 are more vivid among younger members of the group. In this context, in addition to climate anxiety, real estate speculation on the hill, that have been generating major concern.

“Real estate speculation in Vidigal has made the favela a lot more expensive and does not generate income for the community… This trend of people coming from outside and wanting to invest here is not good for the favela, it does not generate income. Things here are very expensive too, which is yet another outrage. More expensive than Copacabana, how’s that even possible?” — Tatiana de Souza Moraes

With spectacular sea views and its prime location on the way between the South and West zones, Vidigal has always been coveted by the financial elite. There was even an attempt to remove the 314 area bordering Avenida Niemeyer under the pretext of safeguarding residents’ lives. It became clear in the late 1970s that the city and state governments weren’t in the least concerned with residents’ lives. According to Mr. Armando, president of AMVV at the time, the 314 area had already been subdivided among real estate entrepreneurs to build mansions. Faced with public managers’ deception, the residents’ association blew the whistle and mobilized everyone possible to stop the threat of removing 314. Celebrities from the arts world, politicians committed to the people, lawyers, clergy and activists from the Favelas Pastoral Committee, and self-employed professionals from different areas joined residents in this endeavor. We won!

In 1996, City Hall carried out containment works in an area at the top of the hill affected by flooding. It turns out this was not exactly for the benefit of residents; Nascimento recalls that the badly affected Rua Carlos Duque was not included in the works. Hotel do Arvrão was built on the site where public improvements were carried out. This incident led some Jaqueira residents to be suspicious of the government’s true intentions. Could it be that they want do they same thing as they did in Arvrão?

While the victimized residents suffered the consequences of the flood, a businessman took advantage of the moment to practically dispossess them from their homes. This way, families were deceived, and convinced to leave their homes.

“Houses were marked. The houses they wanted to buy were marked, right? So, they’d go up to a poor, humble person, put a lot of cash on the table, a stack of small bills… that way, it looked like a larger amount of money.” — Rita de Cassia Machado

Luciana Bezerra, 48, actor, filmmaker, and writer, said that her mother wanted “to live in the Pope’s favela.”

“Sometimes it seems like the Pope came here as a savior. No! That was a lot of organizing from Vidigal! There were already politicized people fighting for their permanence here.” — Luciana Bezerra

André Maurício Gosi, 61, known as Deco, is a former director of AMVV who reflected that the favela has very diverse people, identities, and nuances.

“We have all of Brazil inside a favela… [Vidigal] has now become a tourist spot, which is very famous and even so we have the same problems other favelas have.” — André Gosi

What Knowledge Has the Community Already Developed to Respond to the Challenges Posed by Nature and Climate Change?

According to André Gosi, people didn’t use to migrate to Vidigal for the views. People mainly came due to the history of residents’ struggle, Vidigal’s profound collective wisdom. Gosi also spoke about successful projects implemented in the favela that should be monitored and expanded. These include the community garden on the Niemeyer coastline behind the Djalma Maranhão Municipal School, created by Paulo Cesar de Almeida, a Vidigal resident who founded the Sitiê ecological park, and the Green Roof project at the kombi (transport van) stop.

“What we are doing here today is very important. Discussing climate change. Guto with the Green Roof project at the kombi stop. Paulo, who is making the community garden here.” — André Gosi

It is important to note that the reforestation project carried out in partnership with City Hall was led by the late Sérgio Moreira de Melo, who worked tirelessly for the environmental cause. The project ended and there is no news from the public agency as to whether the work will be resumed.

After lunch in Maria das Graças Prazeres Sabatiê’s sustainable kitchen—another example of Vidigal’s sustainable knowledge—the circle returned to the concern for families in Jaqueira, victims of the last huge flood. Luciana Bezerra made an extremely important point:

“There are 64 families… Homes appear to be just bricks and concrete. No! They’re not just bricks and concrete, guys, they’re families! There are people living in them.” — Luciana Bezerra

Faced with everyday tragedy, many residents normalize their own pain and that of others, possibly as a defense mechanism. Meanwhile they await the next tragedy which will mask over the current one. Maria da Penha from the Evictions Museum had been observing the event. Suddenly, she emphatically declared the central role of struggle as a tool against eviction.

“Only leave here if you want to! People are only evicted when they allow themselves to be evicted. Only 20 families remained [in Vila Autódromo]. It was a prime location, just like it is here. It’s unity that’s lacking. City Hall does just that: it pits family against family, neighbor against neighbor… The favela [must] know how to make noise. You’ve got to get an association, NGOs, residents, everyone. You don’t need to ask permission. Just knock on the door and go in. It’s yours. Yes, there’s a risk of falling. But we’re only heard if we demand to be heard. You’re only here because you made demands. We all have the right to housing. This favela belongs to you, it belongs to me, it belongs to all of us here. The government does not have the right to take you away! It has to do the construction work! Let’s do the construction work together! Removal is not a solution! The right to stay here is in your hands. If your life is at risk, there is an area that can be built on, it’s yours! I want to stay! Because they broke my face, they broke my nose, but I’m still there. I won’t leave and nobody can take me away! They can’t remove you if you’re truly united. There are people, people have said, scholars, that we are past the stage of being enslaved. You will stay! This is my place! Why? Because this is what they left for us! You are a pride… I’m here to help. Marcia came from Cantagalo to do a collective action! Let’s go for it! If there’s a meeting, everyone go!!! Union is struggle, it’s war, wisdom and with lots of love in your heart! Love, comes first. Who doesn’t want to have this view? Now it’s a risk area, soon it will be a rich person’s area. Because someone made that possible… Let’s not drop the ball!… Vidigal resists! Fight! Victory! Long live Vidigal!!! — Maria da Penha Macena

Exemplifying what Dona Penha said, Luciana Bezerra recalled that residents being proactive has provided improvements in Vidigal since it was first settled. She mentioned a teacher “called Eunice, who was here [at Almirante Tamandaré School] around 1984-85, told the story of people building the stairway in 25. It wasn’t the government. It was us.” In addition to Maria da Penha and Luciana Bezerra, Bárbara Nascimento also made a point of highlighting residents’ central role. She shared historical evidence of community-led development in Vidigal by way of news reports from community media. She cited routine measures taken by favela residents in the past that are now advocated as solutions to climate change by experts in the environmental field.

“I brought the newspaper O Mensageiro, which is about collective action. We are here talking about a topic that affects us. Climate change is our issue. We are creating strategies… Houses were made of mud, we reused the water… We have to highlight the solutions.” — Bárbara Nascimento

Agreeing with these statements, Evânia de Paula Muniz reinforced the power of resident activity by raising the issue of garbage. Confronted with government neglect, citizens need to be more careful with what they throw away. She argued that reuse and recycling are old methods in the favelas, which inspired, for example, the collective actions she remembers from childhood.

“We have to see the strength we have. When I was a child, there were collective efforts every Sunday to build housing from recycled materials. Using garbage in a recyclable way. Luxury, not trash. What have you done with your garbage today?” — Evânia de Paula Muniz

Afterward, Bárbara Nascimento and Laelson Alves da Silva presented the proposal for the RUA Project – Urban Reform of the Arts. The aim of the project is to “promote health through architecture.” According to Nascimento, the project reflects the law conceived by Marielle Franco—a Rio councilor murdered five years ago—to guarantee the right to healthy housing for people in favelas. Laelson Alves da Silva added that the project expects to benefit over 1,000 people with the help of City Hall engineers and architects together with partner companies, at no cost to residents. Nascimento and Paiva proposed involving the Vidigal samba school in a large mobilization against the removal of Jaqueira. The samba school brings a lot of people together, hence “it is important to go down with the samba school fighting for the favela.”

Nascimento and Antônio Carlos Firmino from the Sankofa Museum proposed seeking assistance from universities like the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), and Pontifical Catholic University (PUC). They suggested requesting that professionals visit and inspect the Jaqueira region in order to obtain technical reports on the actual risk situation. Firmino says this worked in Laboriaux, Rocinha, in 2011, when the City wanted to remove residents. Following inspection of new technical reports, the houses were allowed to remain.

The Circle ended with the information that the film The Pope’s Favela, by filmmaker Marco Antônio Pereira, was being shown as part of the It’s All True Documentary Film Festival. The documentary was made based on what residents said about Pope John Paul II’s visit to Vidigal in 1980. Circle participants were also invited to go down the hill and visit the Rio Recycles community garden. Invitation made, invitation accepted! Located in another part of the Niemeyer coastline, the project was implemented by Zé from the 314 area, as recalled by Evânia de Paula Muniz, with the aim of cleaning the hillslopes of Vidigal and Rocinha.

Read the entire series of reports on the Favela Climate Memory project.

Don’t miss the album below (or click here to see it on Flickr):

*The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) and RioOnWatch are projects of Catalytic Communities (CatComm).

*The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) and RioOnWatch are projects of Catalytic Communities (CatComm).

About the event reporter: Rita de Cassia Machado was born in Santa Marta and has been a resident of Vidigal for 44 years. She graduated in Law from UFRJ and has a postgraduate degree in Education from UFF. Machado was a community reporter for the O Mensageiro newspaper in Vidigal in the 1980s.