Clique aqui para Português

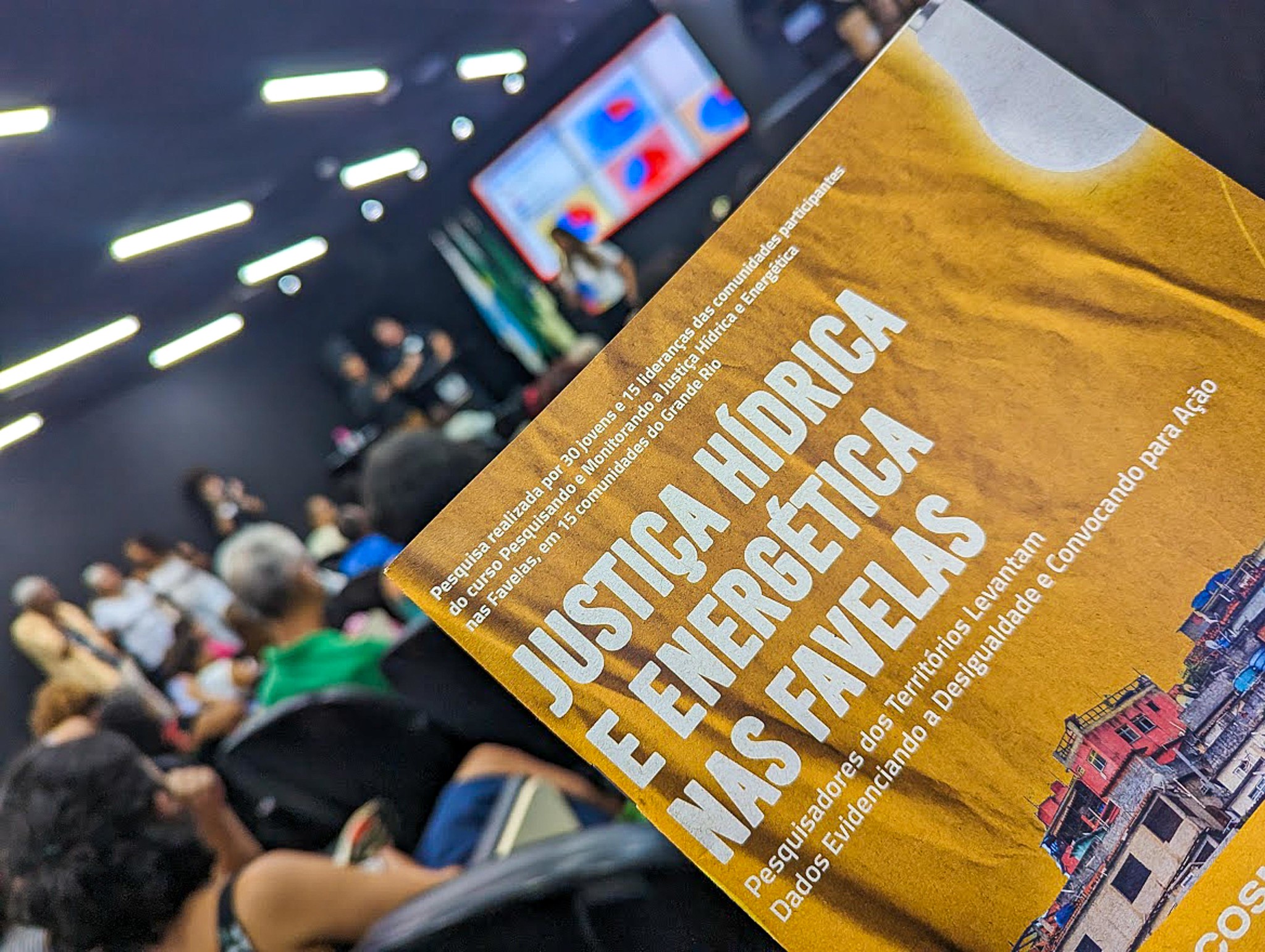

On World Water Day, March 22, the Sustainable Favela Network (SFN), Favelas Unified Dashboard (PUF),* Grassroots Social Education in Solidarity Economy Nucleus (NESPES), Edson Passos Women’s Association (AMEPA), and the Fusion Social Center Association launched the (Portuguese-language) report “Water and Energy Justice in the Favelas: Community Researchers Gather Data Revealing Inequalities and Calling for Action–Mesquita: Coreia, Cosmorama, and Jacutinga.” The event was attended by 100 people and broadcast live on the Mesquita municipal government website.

The event was attended by residents from the three communities reflected in the research—Coreia, Cosmorama and Jacutinga— as well as the largest favela in Mesquita, Chatuba. Also present were representatives from Mesquita’s Civil Defense, Consumer Defense Institute (Procon), Social Assistance Reference Center (CRAS), Municipal Health Secretariat (SEMUS), and advocacy and religious organizations including Casa Fluminense and Chatuba Baptist Church. The event took place in the Mesquita City Hall auditorium.

Organizers of the launch had developed and participated in the 2022 course, “Researching and Monitoring Water and Energy Justice in Favelas,” which resulted in research carried out in 15 communities in cities in Greater Rio de Janeiro, including Mesquita.

Gisele Moura, coordinator of the Sustainable Favela Network’s managing team, opened the event by speaking about the SFN and the event’s program.

“The Sustainable Favela Network is a network organized by community leaders, favela residents, and technical allies who work towards the socio-environmental resilience of favelas in Rio de Janeiro. During the pandemic, the Sustainable Favela Network realized the need to gather and monitor data about [Covid-19 in] favelas. So, a collective conversation emerged, and community leaders [developed what would become] the Unified Dashboard. [Later, they determined what other] data would be of great importance to [be collected] in their communities and water and electricity… [were among the] most important themes… The idea of the Favelas Unified Dashboard… [is that] communities can gather and be agents of these data.” — Gisele Moura

Why Water and Electricity? How Are They Linked?

In the report “Water and Energy Justice in the Favelas,” Amanda O’Hara from the Brazilian Climate and Society Institute which supported the research program writes that “electricity and water are two intrinsically dependent resources. Especially in Brazil and especially in low-income communities.” She points out that, with the water crisis in 2021, Brazilians had to deal with a hike in electric bills, due to the lack of rain that reduces the water level in dams, “reducing the availability of water in hydroelectric plants to generate electricity.”

Beyond water shortages, the report recorded serious water quality problems, constant flooding, leaks, and negligence by the utility in providing quality service. Similarly, higher electric bills have direct consequences on access to food and the quality of life of families, who also suffer from negligence and blackouts. The data also showed that it takes a long time for the water supply to renew.

Luiz Miguel Ribeiro and Matheus Botelho, youth members of NESPES and residents of Coreia, were the researchers responsible for gathering data in their community. They presented the data while also asking questions to the audience about their realities regarding lack of water and electricity, which sparked descriptions and outbursts from those present. The data presented included demographic profiles, water access, quality, and efficiency; and electricity access, quality, and efficiency.

“In each community, around 75 people were interviewed, so, our investigation does not reflect the community as a whole. It seeks to provide an idea about the situation and combine with other communities to show a panorama of our metropolitan region. The vast majority of people interviewed… were women… and the majority of interviewees [self-identified] as Black… the majority of those reflected in the data… are Black.” – Matheus Botelho

When the audience was asked about the quality of water, Sabrina Moreira, a resident of Coreia, commented that “the water has sludge, it’s yellow. When there’s no water, it comes back full of mud.”

Two other youth participants in the research shared their experience with data collection. Matheus Edson from Rio das Pedras spoke about problems related to water, electricity, and social and environmental injustice that should not be normalized. Janyne Lima, from Itacolomi, Ilha do Governador, described the fieldwork involved in the study and what she heard as she spoke with her neighbors, including reports from people who had to purchase their own streetlight and others without piped water at home or who do not have a water tank.

Many residents from the Chatuba favela described the same problems in their community, such as high electric bills and lack of water. Resident Maurílio Costa shared ways of economizing:

“I think it is outrageous to charge R$ 360 [US$ 76] for water in a community that… when the water is off—[for example] today is Wednesday, the day the water shuts off—what do I do? I fill the water tank and close the meter. Next Wednesday I don’t need any since I already have water in the tank.”

Zeca Pereira, another resident of Chatuba, reported: “since Águas do Rio took over [as the privatized water utility], we have the same problems we had with CEDAE [the previous public utility] but they have doubled.” Luiz Simplicio commented about Mr. Ivan, a Chatuba resident who voluntarily keeps his pump running 24 hours a day to supply the community, since Águas do Rio went there and ignored problems reported by residents.

Community organizers Tânia Alexandre da Silva, coordinator of AMEPA, Ana Leila Gonçalves, coordinator of the Fusion Social Center Association, and Laurinda Soares, coordinator of NESPES, described the central role youth played in the research and called on residents to become more engaged. They also commented on giving continuity to activities initiated and making proposals for coordinating and integrating public authorities with professionals from within the favelas.

Watch the Video in Portuguese Here.

Check out the photo gallery below, or click here to view on Flickr:

*The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN), Favelas Unified Dashboard, and RioOnWatch are initiatives of the NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm).