Clique aqui para Português

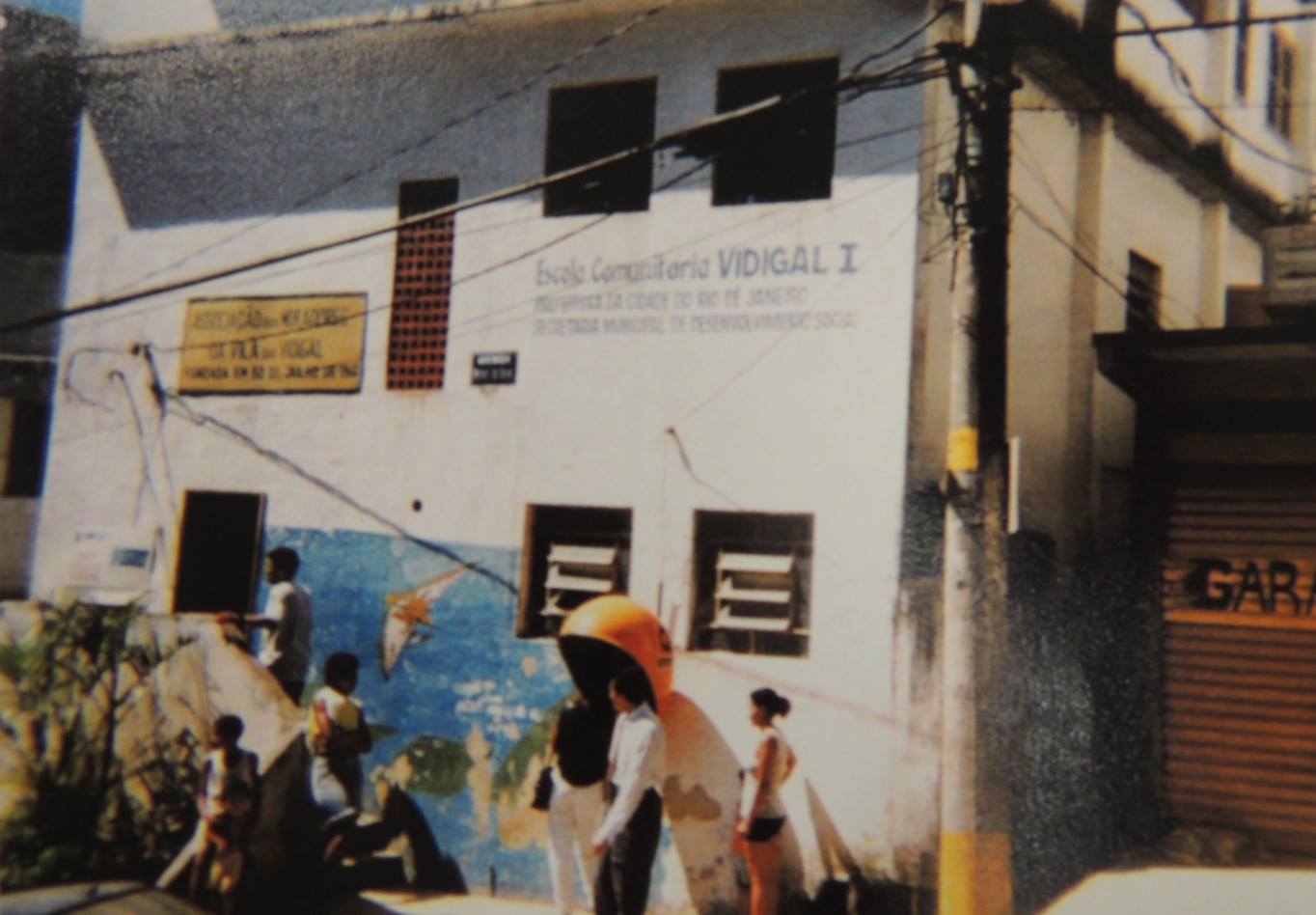

In 2023, the Favelas Pastoral Committee celebrates its 46th anniversary. A Catholic Church institution, the Pastoral Committee holds a rich history of supporting the struggles of Rio de Janeiro’s favela residents. A pivotal moment was the successful defense of Vidigal residents in the South Zone of Rio in response to an attempted eviction during the military dictatorship in 1977. Much like thousands of residents across South and North Zone favelas in the preceding years, they received abrupt notices from government officials. Residents were informed, without dialogue, that they had to vacate their homes and would be relocated to Santa Cruz, in the West Zone, 50 kilometers away.

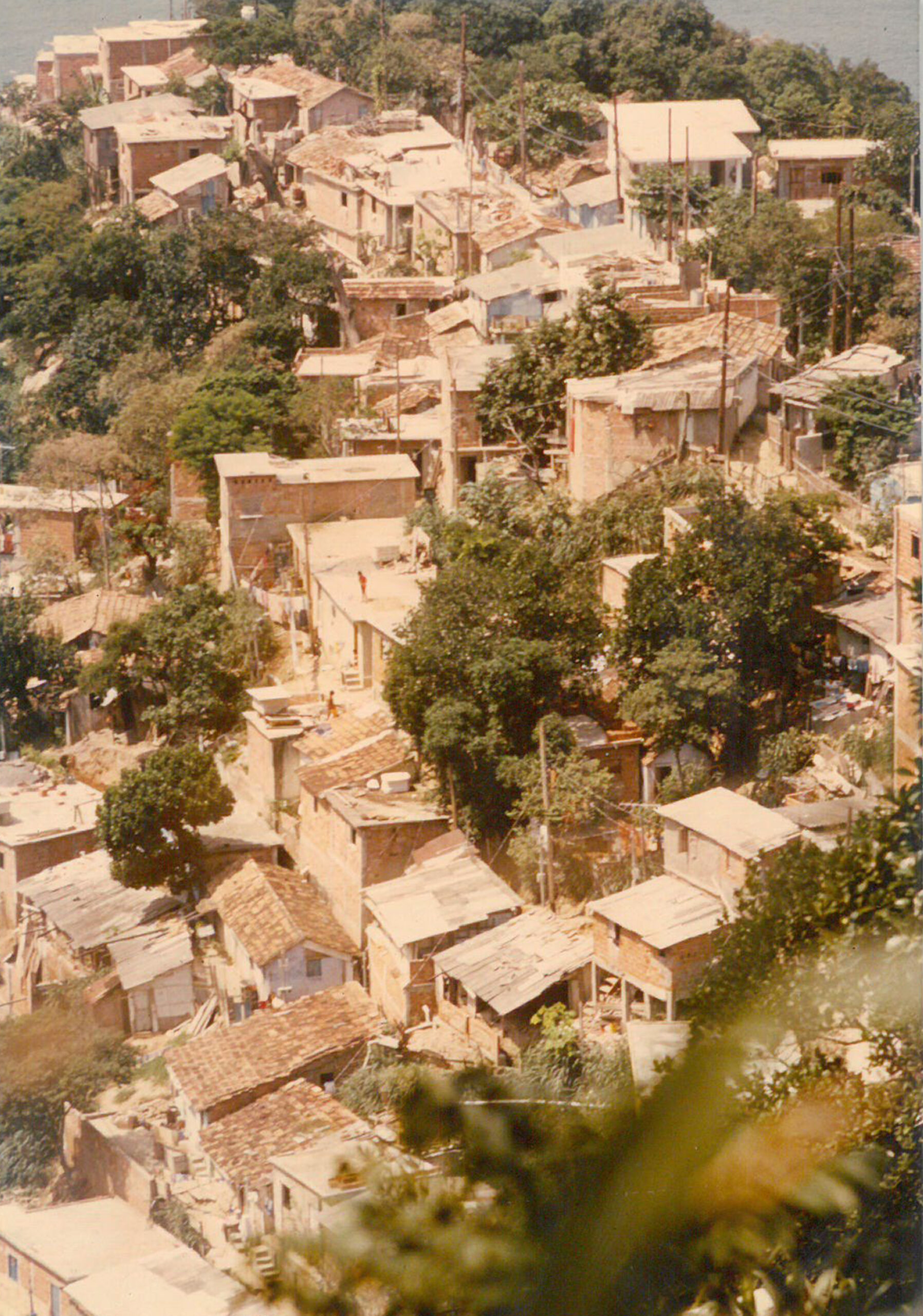

Let’s pay special attention to the context surrounding this event. The Vidigal favela is located on a mountainside overlooking the sea, boasting one of the most stunning views of Rio de Janeiro, from which one can see the ocean and various touristic landmarks, including Leblon and Ipanema beaches, and a portion of the Guanabara Bay. Beyond its scenic beauty, the favela occupies a strategic position on a crucial route, Avenida Niemeyer, connecting the South Zone to Barra da Tijuca. At the time, Barra was evolving into a new focal point for real estate expansion, catering to the middle and upper classes.

Vidigal is also close to the neighborhoods of Gávea, Leblon, Lagoa, and São Conrado—Rio de Janeiro’s most affluent neighborhoods today. Between 1969 and 1973, these areas experienced the majority of the city’s favela removals. Major favelas like Praia do Pinto, Parque Proletário da Gávea, Catacumba, Macedo Sobrinho, among others, were completely eradicated. Their areas underwent drastic demographic changes; they were until then industrial neighborhoods inhabited by Black workers. This eviction program amounted to an ethnic cleansing process, displacing tens of thousands of families to the outskirts of Rio. They took place during the peak of the military dictatorship, established in Brazil in 1964, always accompanied by a strong repressive apparatus and threats to residents daring to resist. During this regime, any simple arrest could turn into the torture and disappearance of residents, leaders, and activists.

In this context, the organization of Vidigal residents against eviction took on a dual nature. On the one hand, their organizing served as a litmus test for the democratization process that Brazil was beginning to undergo. In the words of Ernesto Geisel, the fourth of the five dictators who presided over Brazil between 1964 and 1985, democracy would return to the country in a “slow, gradual, and secure” manner. It took immense courage to challenge an action of the State that, only a few years prior, carried serious risks. On the other hand, the resistance itself became a catalyst in speeding up the redemocratization process.

Organized residents of Vidigal sought the support of Father Ítalo Coelho, a parish priest in Copacabana, whose congregation included military personnel, businessmen, and their wives. Father Ítalo, a man of profound culture and sensitivity to social causes, founded the Favelas Pastoral Committee as a means of formal assistance and Christian charity for the residents of favelas. Upon meeting with Vidigal residents, Father Ítalo connected them with lawyers dedicated to human rights causes, such as Sobral Pinto, Bento Rubião, and Eliana Athayde. By the end of 1977, these lawyers successfully halted the eviction through legal means: Vidigal residents would remain in their homes.

Vidigal’s victory made waves across Rio’s favelas, and the Pastoral Committee took on an increasingly significant role in supporting community organizers and standing with residents in their fight for security of tenure. Organized residents in areas facing eviction began turning to the Pastoral Committee, which formed working groups and later provided support in the creation and democratic disputes of residents’ associations. These associations were, until then, heavily controlled by the State, a legacy of an institutional framework set up during the military dictatorship—a framework that allowed the State to intervene and remove the boards of directors from these associations at will.

The Pastoral Committee was a welcoming umbrella for many residents, who saw it as a way to organize collectively. Moreover, the lawyers’ efforts aimed at encouraging residents’ organization, mentoring their political development, and awakening them to the struggle. This process further solidified individuals who are still key figures in community organizing in the favelas, such as Itamar Silva from Santa Marta, Eliana Sousa e Silva from Nova Holanda, Paulinho from Vidigal, among many others.

It is worth noting that, during the dictatorship, different sectors of the Catholic Church took opposing positions. The high hierarchy of the Church in Brazil had supported the military coup of 1964, which ousted President João Goulart. However, a few years later, some priests and nuns provided shelter to students, unionists, and other opponents of the dictatorship. There were even priests who chose to support left-wing guerrillas, and as a result, they were arrested, tortured, and killed by the military.

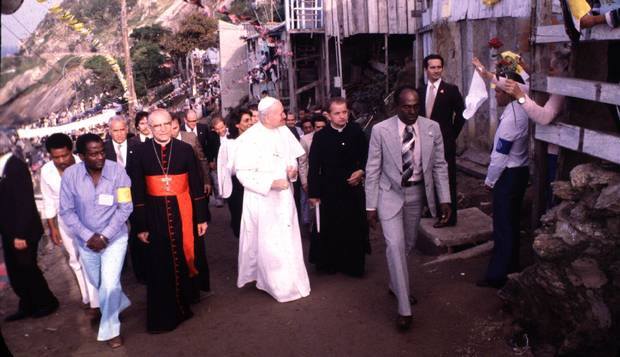

Nonetheless, in the late 1970s, the Catholic Church in Latin America experienced the impact of the II and III General Episcopal Conferences of Latin America, held in 1968 in Medellín, Colombia, and in 1979 in Puebla, Mexico, as well as the Second Vatican Council. These were milestones in the change of the pastoral stance of the Catholic Church in Latin America, which adopted the Preferential Option for the Poor, a doctrinal principle that served as the foundation for the development of Liberation Theology. This theology advocated for a Church attentive to the struggles of the poorest for freedom, rights, and social justice, mobilizing clergy and laity to uphold organized grassroots movements.

In Brazil, this was reflected in the robust backing of part of the Catholic Church to social movements, including support to unions and strikes, the reestablishment of the National Union of Students (UNE), which was made clandestine by the dictatorship, the creation of the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST), and the founding of the Workers’ Party (PT).

Thus, at the end of the dictatorship, during the transition from the 1970s to the 1980s, the Favelas Pastoral Committee played a crucial role in defending Rio’s favelas. On a larger scale, it was instrumental in Brazil’s redemocratization by shaping leaders, fostering community organization, and assisting residents in the struggle for housing rights.

Having fulfilled this role, the Pastoral Committee entered a slower period starting in the mid-1980s. Many leaders who had been at the forefront went on to occupy other spaces, such as the Federation of Favela Resident Associations of Rio de Janeiro (FAFERJ), political parties, and positions in government—all resulting from the redemocratization process.

The intense community organizing of the late 1970s and early 1980s gave way to residents’ associations, characterized by direct engagement with government channels. Those who had better relationships with the ruling authorities could secure more benefits for their communities through various projects, actions, and programs in the favelas. The successes from the struggles of the earlier period ushered in a new set of higher level challenges, shifting from the previous focus on security of tenure. For Rio’s favelas today, the majority of demands no longer revolve around the right to remain but, instead, center on the consolidation of the right to tenure through infrastructure, public services, and improved living conditions.

Starting in the 1990s, the main challenge for the community movement was the presence of gangs of drug traffickers in favelas, and the State’s response. The war on drugs is characterized by the violent action of the State, armed conflicts, numerous massacres, and poor police intelligence. However, in the 2000s, the problem was further exacerbated with the expansion of off-duty police mafias known as militias.

At the end of the first decade of the 21st century, with the city of Rio de Janeiro seeking a new vocation as a host for events, coupled with the expansion of real estate credit in the early federal administrations of the Workers’ Party (PT), favelas once again became targets for removal. Under the justification of security, environmental damage, or even the need for infrastructure works to prepare the city for mega-events like the 2014 World Cup or the 2016 Olympics, favelas such as Vila Autódromo, Metrô-Mangueira, Providência, Vila Harmonia, Largo do Campinho, Tanque, Vila União de Curicica, Pavão-Pavãozinho/Cantagalo, Indiana, Horto, among many others, entered the list of areas slated by City Hall for total or partial removal.

Once again, shoulder to shoulder with residents, the Favelas Pastoral Committee took on the fight in defense of their rights. Now, in a new context, there have been legislative achievements such as the right to compensation, urban adverse possession, the guarantee that removal should only take place as a last resort, as well as the possibility to call upon the Judiciary, and to coordinate residents with the press, the legislative power, universities, architects, engineers, and more. Unfortunately, legislation alone is not enough, and the fight through the organization and unity of residents, along with supporters, remains the most crucial mode of defense. This gave rise to the Pastoral Committee-facilitated Popular Council, that since 2007 has held monthly meetings amongst favela leaders fighting eviction, holding exchanges, organizing protests, and providing legal defense at various state levels, with the aim of effectively ensuring the right to housing and the city, a right still disrespected to this day.

About the author: Mario Brum is a historian, urban planner, educator, and researcher of urban, land, social movements; public policy; identity; and stigma. He is a member of the INCT Proprietas, coordinator of the Vozes da Luta Extension Project (UERJ), and professor in the Department of History and ProfHistória of the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), as well as a Procientista-UERJ.