Clique aqui para Português

The frequent problems related to water access faced by residents of Greater Rio de Janeiro were debated during a recent public hearing entitled “The Human Right to Water: High Fees and No Water?” The session, held at the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ) on November 29, was called by the body’s Human Rights Commission, chaired by State Representative Dani Monteiro.

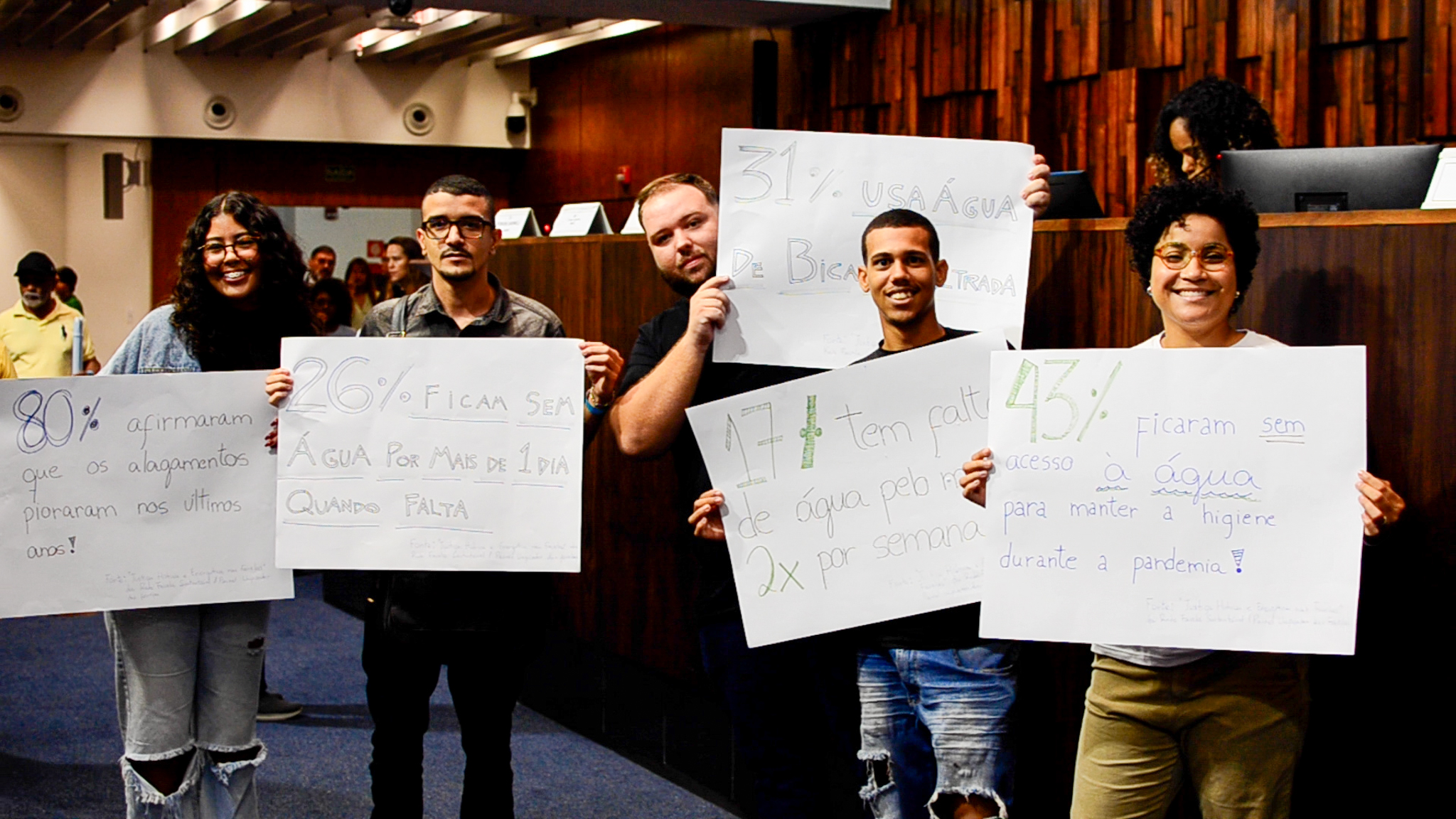

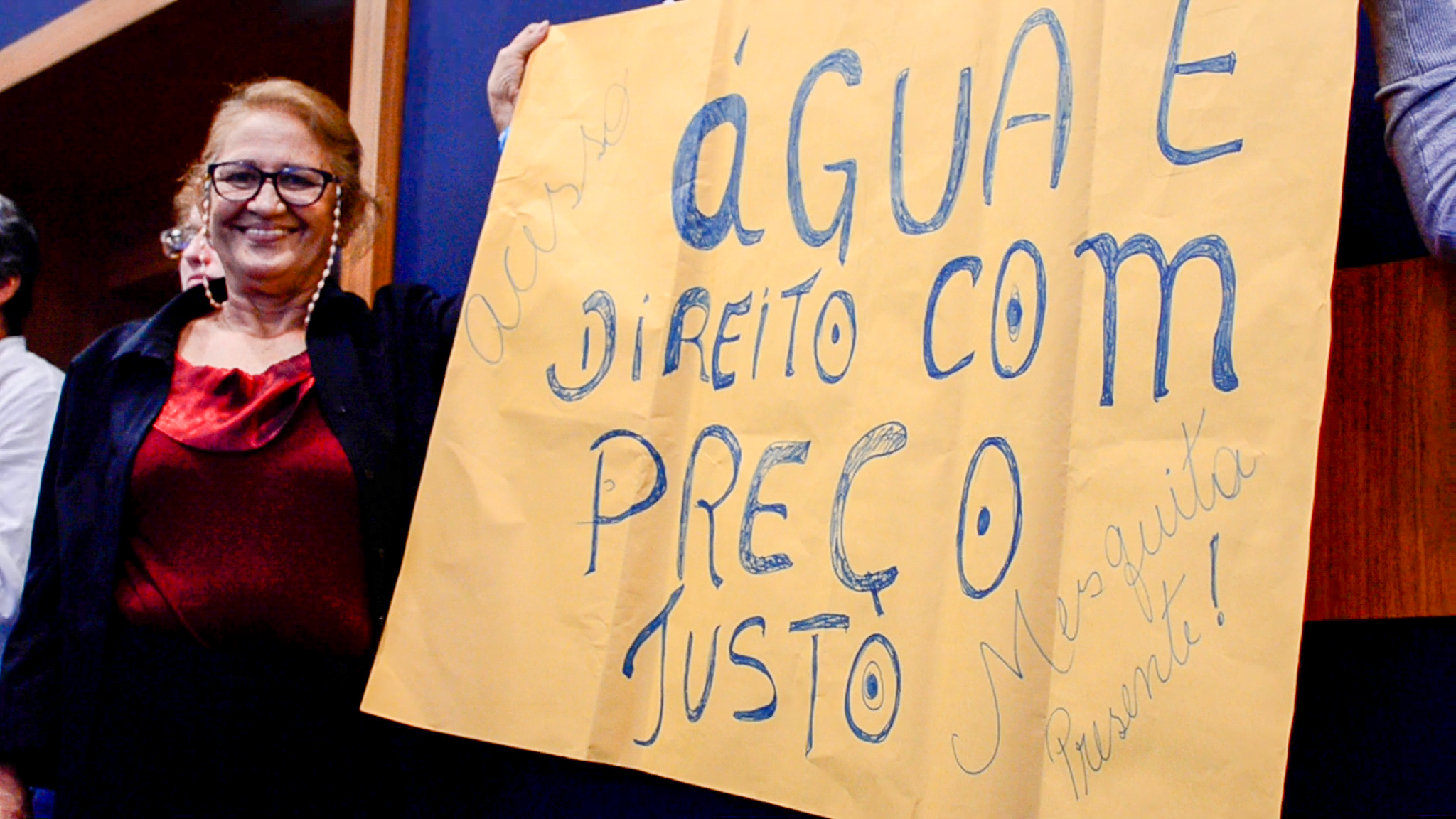

Some 100 residents from favelas across Rio de Janeiro protested the region’s water service with posters and public comment, including residents of Rio das Pedras, City of God and Rua Icurana in the city’s West Zone; Rocinha in the South Zone; Providência and Morro dos Macacos in the Central Zone (Planning Area 1); Itacolomi, Vigário Geral, Vila Cruzeiro, and Jacarezinho in the North Zone; Éden in São João de Meriti; Coréia in Mesquita; and Vila Alzira in Duque de Caxias. The latter three, are located in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region.

The alleged benefit that would be generated by the privatization of water services for the population was one of the primary questions from the audience, along with complaints of abusive rates and concern over the effect of extreme weather events. The hearing also included representatives from the Brazilian National Development Bank (BNDES), the People’s Watchdog Network for Sanitation and Health, the Public Defender’s Office, the State Water and Sewerage Company (Cedae), the Energy and Basic Sanitation Regulatory Agency (Agenersa), the Rio de Janeiro Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPRJ), and private water utility Águas do Rio.

On the hearing’s panel, and based on data from the report “Water and Energy Justice in the Favelas: Community Researchers Gather Data Revealing Inequalities and Calling for Action” carried out among 1200 interviewees in 15 favelas by the Sustainable Favela Network (SFN),* urban planner Theresa Williamson of Catalytic Communities,* detailed the data and impacts of poor water access in Greater Rio. Of the families covered by the study, 17% suffer from lack of access to water at least twice a week. “If these data were to reflect all favelas in Rio, that would mean 270,000 people are without water twice weekly.” Another point raised was the issue of electricity, which proved to be a determining factor for access to water: 48% depend on a pump to bring water into their homes. The quality of water resources was also addressed.

“The study showed that this resource, which Brazil enjoys in abundance, does not reach its citizens adequately, despite the discourse of public authorities and service providers. It is worth remembering that Brazil is the country with the largest freshwater resources in the world. Brazilian law says: ‘By 2030, we will achieve universal and equitable access to water for human consumption, safe and accessible to all. Regardless of social, economic or cultural standing.’ So the objective of any water policy is to achieve universal access. The WHO points out that for every one Brazilian real invested in sanitation, there is a saving of four reais in public health. Also according to the WHO, however, Brazil provides water to 99% of its population. But we know that this is not true. These data are produced from the outside, [by individuals] who never even enter the [affected] areas, [through research] that does not generate a true understanding.” — Theresa Williamson

Another concerning aspect of the problem is the amount that favela residents end up paying for this basic service necessary to their survival. Vigário Geral resident Tereza Mariano was shocked in March 2023 when she saw the water bill arrive. Resident of an area known as El Shadai, the self-employed salesperson received a bill for R$1,299 (US$266). Since then, the bills have not come below four figures.

“I managed to pay some, but with that amount I had to choose between eating and having water in the tap. Now they’ve cut off the supply, even though the invoice address shows an unregistered plot of land. Ours is a small occupation, where around 35 families live. They could register us, but I think the real intention is to remove us from the site… Our fear is that they will use these bills to evict us from where we are. We have no right to anything, not water, not housing. We need a social tariff. There is no life without water.” — Tereza Mariano

Flávia Lima de Oliveira, from Recanto da Areinha, in Rio das Pedras, believes that the poor service provided by the water utility that manages distribution to residents of Rio’s favelas is intentional. She recalled that, in the week in which the city’s thermal sensation exceeded 50ºC, the community spent almost ten days without water.

“We live in one of the most deprived areas in the region. And the water [supply] keeps going on and off. That week, the situation was inhumane. Children were left without water, the elderly too. And the heat punished everyone. This is all orchestrated, to diminish us. Water should never be treated as a bargaining chip. Anyone who lives on Bolsa Família (welfare) should be kept out of this logic of absurd fees. We don’t have the financial means.” — Flávia Lima de Oliveira

Is Water a Commodity?

Since the privatization of CEDAE, in 2021, the people of Rio de Janeiro have suffered from increased fees for water, while many have also been impacted by distribution problems. The private sector water utility Águas do Rio, now responsible for distributing the resource, has been the target of criticism since it took control of the sector.

At the panel table, Luciana Capanema, representing the Brazilian National Development Bank (BNDES) emphasized that, in exchange for privatization, corporations in the sector are expected to invest around R$1.8 billion (US$367,414,380) to enhance water and sewerage services in Rio’s unserviced favelas. However, Capanema’s speech left uncertainties about how these funds would directly benefit the population. The scope of the public bank’s investment also envisions an unrestricted expansion of the coverage of the water social tariff.

“Brazil has been making efforts in terms of promoting public policies to universalize water since the 1970s. But this effort has proven insufficient. We say that BNDES is agnostic. For us, it doesn’t matter whether the person providing the solution is a public or private utility. What matters is that the proposed service is delivered to the population. And then we will finance it to achieve this goal. Remember that treated tap water has a cost. So, that’s why it is made possible via a fee. But it is clear that the fee needs to be set up in a way that everyone has access.” — Luciana Capanema

Sinval Andrade, from the private utility Águas do Rio, broadly asserted that those providing public services should be transparent and subject to social control. According to the superintendent director, the utility is in direct contact with local leaders, residents’ associations and other civil society organizations in 700 partner communities, representing 11 million people. Of this total, 525 are in Rio de Janeiro proper.

“We’ve worked in several communities, investing around R$2.1 billion (US$425,308). We laid 963km of water network and 270,000 people had access to water for the first time, since we took over the service. Currently, 13% of our customers are registered under the social tariff.” — Sinval Andrade

At that point, State Representative Dani Monteiro questioned the director on the standard procedure for applying for the social tariff. She pointed out that the Human Rights Commission receives many complaints about the benefit not being granted. This came after the director mentioned that the criteria for the tariff were regulated by a decree. However, he could not pinpoint the legal mechanism behind it, only mentioning a study to automatically include customers registered with CadÚnico [the federal government’s Unified Registry program] in the low-income category.

Next Steps

At the conclusion of the debate, the panel chaired by Representative Dani Monteiro proposed taking steps towards building a public monitoring platform and fostering citizen-generated data on water. The session highlighted the urgent need for the swift approval of a bill that regulates the social tariff, provides exemption and amnesty for unfairly charged amounts, enhances monitoring and control of water potability, and establishes the creation of user councils to boost public participation in debates on the topic. Furthermore, the deputies were urged to consider the creation of a state-recognized day to promote water security.

Watch the Full Video of the Public Hearing Here:

Don’t miss the album by Patricia Schneidewind (or click here to view on Flickr):

*The Sustainable Favela Network (SFN) and RioOnWatch are both projects of NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm).