Clique aqui para Português

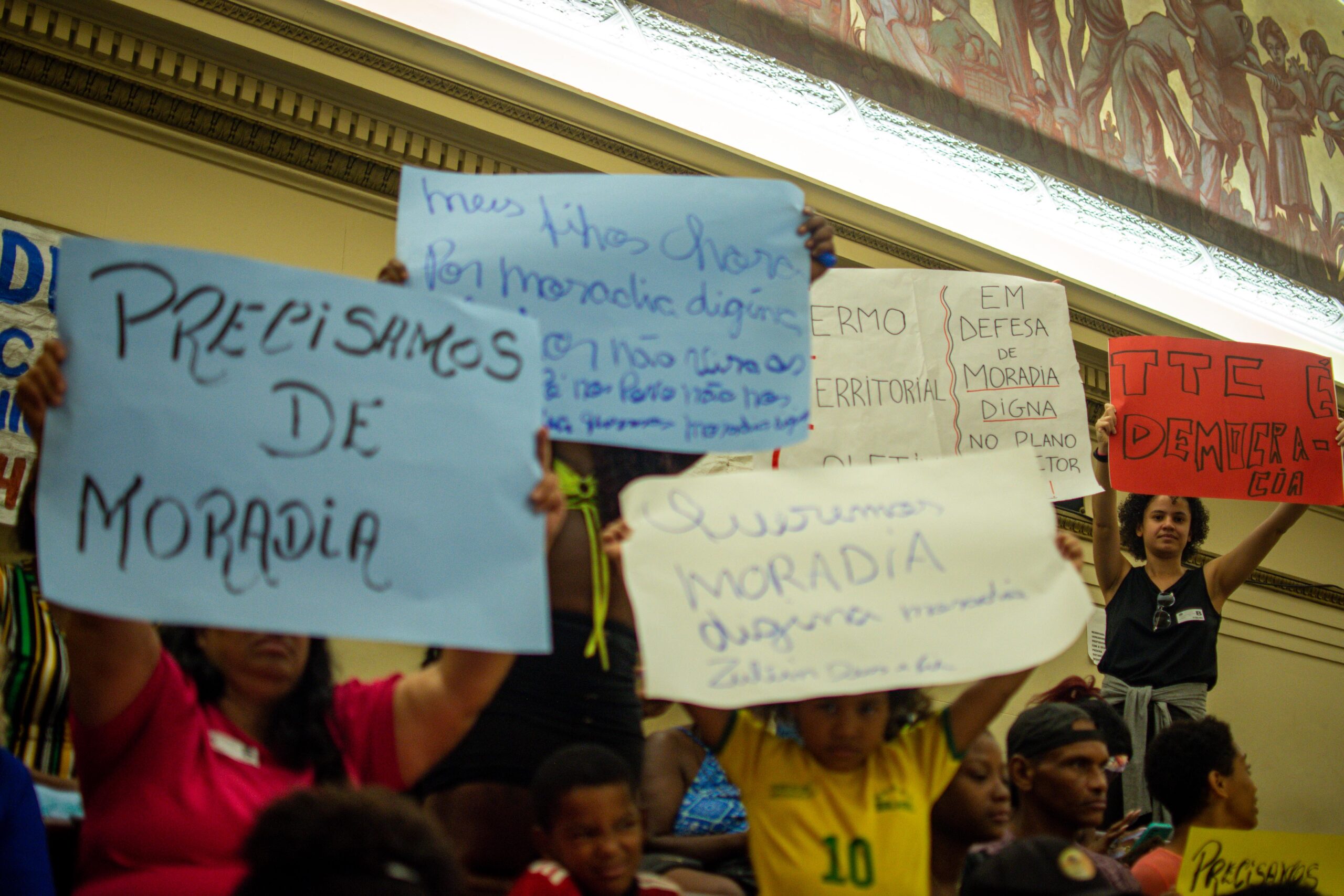

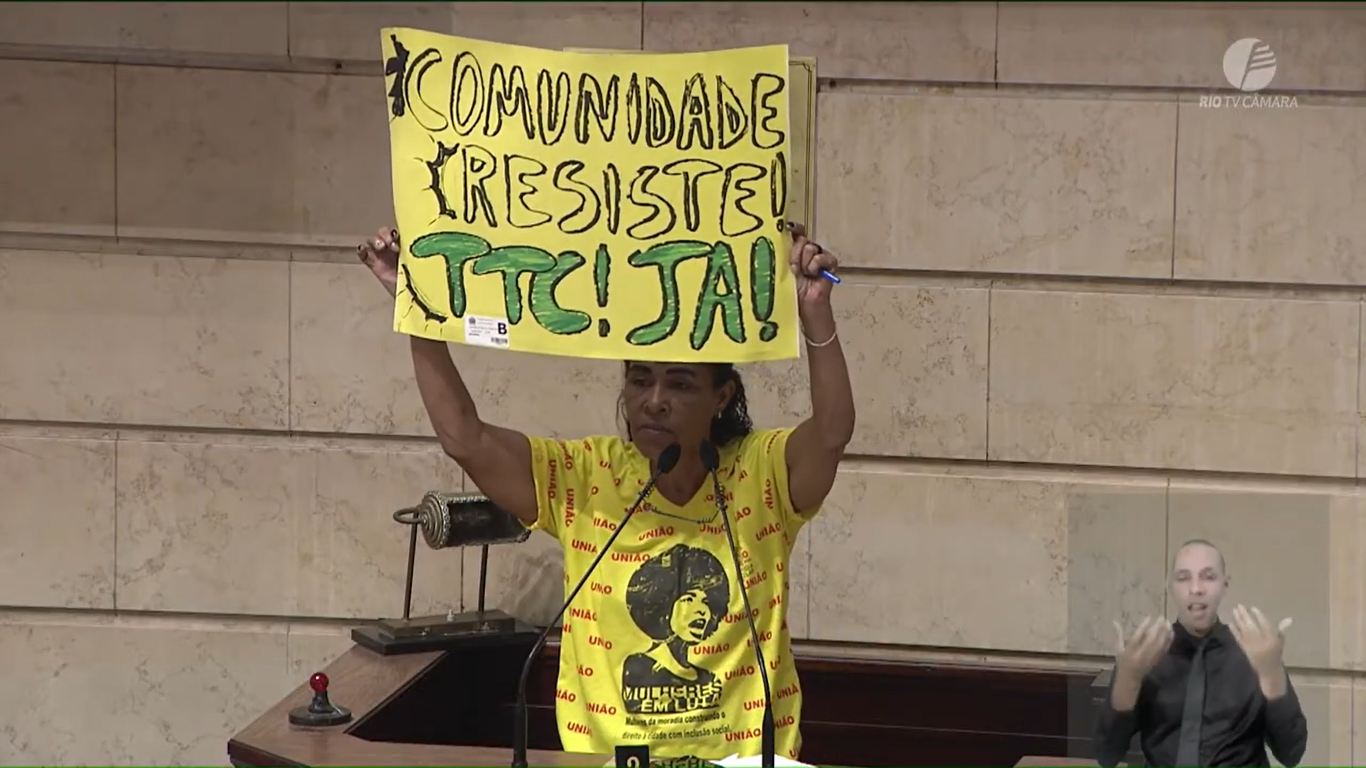

The city of Rio de Janeiro officially has a new Master Plan. In an extraordinary session held on December 11, 2023, councilors approved Bill Complement No. 44-A/2021, instituting the new Master Plan for the city with 37 in favor and 10 against. The Master Plan is the fundamental urban law at the municipal level. It establishes guidelines for urban development over the next ten years, and outlines the available policies. In Rio’s updated Master Plan, two key measures stand out with potential impacts on Rio’s favelas: the Community Land Trust (CLT)*, as a new recommended instrument of urban policy, and a chapter specifically aimed at the city’s favelas. The CLT represents an innovative land management model, which aims to guarantee the tenure security of residents when their territories are faced with forced evictions and gentrification. It was originally part of the Master Plan but was removed by the city through an amendment in late 2022. This sparked a reaction from civil society, leading to civil society organizing in the Rio de Janeiro City Council chambers. The popular movement was instrumental in the reinstatement of the CLT in the Master Plan.

The bill, previously approved in the first vote, received a total of 1,236 amendments from councilors. The session that approved the plan only analyzed legislative amendments, of which 475 were accepted. Over ten hours of discussions were held, in which various requests for changes were debated among councilors. Ultimately, they chose to enact the law proposed by the executive branch, incorporating alterations from the amendments. After the vote, the Master Plan moved on to Mayor Eduardo Paes to be sanctioned or vetoed.

In general, urban planners point out that the new Master Plan is more aligned with market interests, with an aim of reducing bureaucratic processes and conceiving the city as commodity. From a social perspective, especially with respect to housing, the plan still has much room for improvement, requiring the passage of new laws such as in order to fully implement the CLT, or “Parcelamento, Edificação ou Utilização Compulsórios” policies, the latter of which may be used to convert abandoned properties into housing. Furthermore, the plan leaves out other instruments that would also be important in improving housing provisions in the city, such as inclusionary zoning, which would have required that every major housing development set aside a percentage of its units for low-income residents.

The review of the Master Plan was a long process which began in 2019, impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic and marked by setbacks and disagreements. According to the City Statute, the review of master plans across Brazil should be a participatory process in which all of society is invited to discuss the direction of urban development and defend their visions for the city. The principle of democratic city management should be respected in this critical moment, which will decide what urban policy will look like for the next ten years.

Despite having started in 2019, the process was interrupted and only resumed in 2021, with a very short schedule of debates within the executive branch. This sparked public criticism regarding the limited opportunity for popular participation granted by the city. It wasn’t until the bill reached the City Council that a significant window for public involvement opened up.

The law introduces many new features to the city’s spatial organization, particularly impacting favelas and urban informal settlements. Despite comprising a significant portion of the city’s area and housing around 24% of Rio’s population, favelas have never been completely incorporated into Rio’s organized urban planning. Interventions in these spaces have historically been limited in scope and continuity, resulting in specific improvements but limited long-term or holistic impacts. Furthermore, favelas are subject to a policy of criminalization and continuous repression by authorities, reflecting a violent manifestation of the structural racism that permeates our society. All of this points to a historical debt that the city of Rio de Janeiro owes to its favelas.

The new Rio de Janeiro Master Plan brings important changes to the treatment of favelas by the city’s managers. An entire chapter dedicated to the favelas was included, with guidelines, rules, and resources to encourage a better approach to addressing these spaces with effective public policies. Chapter 4: On the Right to the City, Land and Adequate Housing in Favelas recognizes that favelas are legitimate components of the city as a whole, highlighting their particularities and, above all, their qualities which include cultural wealth, solidarity networks, social diversity, mechanisms of self-governance, and female leadership, among others. For the first time in the history of Rio’s urban planning instruments, favelas are defined not solely by what they lack but also by their unique potential.

Beyond the symbolic importance of recognizing favelas for their potential and opportunities, the chapter also includes various guidelines on what should define urban policy in favelas. It emphasizes the need for participatory and consistent management in these spaces, listing relevant measures to improve residents’ living conditions, such as land regularization, the provision of fundamental urban services like transportation and sanitation, risk mitigation, technical assistance for social housing, and adapting favelas to climate change and promoting resilience. Despite these advances, several provisions that set deadlines and specific obligations for public authorities were removed via amendments proposed by City Council members aligned with the Mayor. In an interview, the author of the amendment, Councilor Tainá de Paula, highlighted the importance and uniqueness of including a chapter solely pertaining to favelas in the Master Plan.

“I am an architect and urban planner who, for 20 years, has worked on this topic in Rio de Janeiro and in Brazil. Never in the city’s history has the Master Plan been dedicated to the urban planning of favelas, and finally, a chapter about them has been included, treating them with respect and dignity. Better late than never! This is crucial because it will determine the allocation of resources from the Housing Fund and from Fundurb [municipal urban development fund]. This has moved beyond the realm of ideas.” — Tainá de Paula

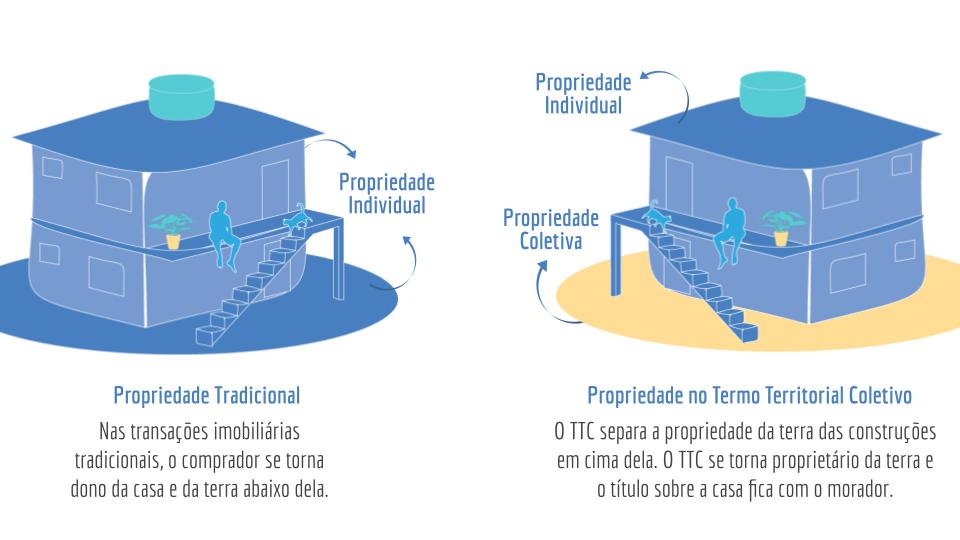

In addition to the chapter on favelas, another important factor that will impact these territories is, as mentioned earlier in this article, the approval of the Community Land Trust (CLT). Applied in several countries around the world and internationally recognized for its effectiveness in guaranteeing adequate, affordable housing, the CLT is a model of collective land management characterized by the separation of land ownership, which is collective, from building ownership, which is individual. The primary contribution of CLTs is to strengthen security of tenure and community power ensuring that residents have the right to remain on their land and agency in the development of their territories.

With its approval in the Rio de Janeiro Master Plan, this is the first time that the CLT instrument is legally recognized by the city and included among its possible tools. It aims to ensure the right to access land and housing (articles 169-172), strengthen communities, and protect against threats of forced evictions. Rio de Janeiro is now the second Brazilian municipality to include CLTs as a recommended instrument in its Master Plan, after São João de Meriti. This was a great victory for all those who fight for housing rights in the city. However, despite the well-deserved celebration, it is important to highlight that an explicit provision was included, stating that the CLT can only be implemented after regulation by specific law. Given that the CLT could already be applied even without a provision in the Master Plan, this stipulation remains inadequate and demonstrates a lack of will on the part of City Hall to fully support the model’s implementation.

The future implementation of CLTs will break from the common precedent of top-down intervention policies in favelas, instead allowing for greater opportunities for community leadership. The model offers a higher degree of security of tenure, protecting communities from various threats of eviction, whether initiated by the State or arising from market forces (i.e. gentrification through real estate speculation).

With these advances for favelas in the Rio de Janeiro Master Plan, the city will have new tools at its disposal to give these territories more of their due importance in urban policy. However, legal provisions alone are not enough. They must be implemented, moving beyond on-paper theory to be fully realized. For this, continuous popular struggle is fundamental, maintaining pressure on public authorities to ensure that favelas are effectively respected and prioritized, no longer neglected in the city’s budget, and receiving long-term interventions genuinely aligned with the interests of residents.

Watch the Recording of the Public Hearing Here:

*The Favela-CLT Project and RioOnWatch are both initiatives managed by Catalytic Communities (CatComm).