Clique aqui para Português

At 3:27pm on January 17, 2023, Maria* lost her Internet connection at home in Piedade, situated between the neighborhoods of Méier and Madureira in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro. Initially, Maria thought the issue might be due to wind or kite strings entangled in the cables, expecting the connection to return soon. However, hours went by, and the Internet did not come back. She contacted Claro, her Internet provider, and was informed of network instability in Piedade and surrounding areas. The company mentioned that technicians were in the region trying to identify the causes of the problem but provided no estimate for the resumption of service.

As a self-employed professional in design, marketing, advertising, and publicity, Maria operates without labor rights or guarantees, relying on her home Internet service for her livelihood. Without a reliable connection, she is unable to generate income or pursue her studies. Though she can watch online classes later, her work cannot be postponed.

Racing against time and fearing delays that could lead her to lose her employment, Maria inquired about Internet access at her neighbors’ homes. Her plan was to work from a nearby house with a stable Internet connection. But her neighbors were also disconnected, and, like her, were all deeply concerned. Many rely on the Internet for various daily tasks, including work, study, and even transportation.

The only alternative she found was to use the mobile Internet on her phone to try to maintain her routine. However, due to the poor quality of the local phone signal, it took longer than usual to perform simple professional tasks, such as working on Google Drive and sending or receiving emails. Afraid of falling behind, she worked through the night using a 3G connection and missed two classes.

On January 18, broadband had still not been restored, neither at her home nor at her neighbors’. Maria also lost access to cable TV provided by the same Internet company. When contacting Claro, she was informed that there was no timeline for the network’s return due to public security issues. The representative emphasized the severity of the situation, stating that the technical team had been withdrawn from the area due to serious threats made against them.

With no other option, Maria canceled the long-standing contract with the provider she had subscribed to for years. She had to negotiate with the company to waive the charges for the days without Internet access. Then, she reached out to a company that had recently left a leaflet in her mailbox. Although this company was not well-known to the public, it had already been providing Internet services to a few of her neighbors before the major providers were forced out. According to local residents, the company had been serving the area for a few months.

Established in 2016, the small business operates from a residential address, quite distant from Maria’s home. Nevertheless, it seems to be providing Internet services in Piedade in relative safety, while large national service providers, present across the country, cannot access the area and work safely.

Maria contacted the new company and subscribed to the 300 Mbps plan for R$82.90 (US$16.70), a similar amount to what she paid her previous provider. The small company, without providing a specific timeframe, stated that they would visit her residence in a few days to install and configure the modem. Those few days turned into seven, and on January 24, they finally installed the Internet. Two technicians, without uniforms or badges, arrived in an unmarked Fiat Premio CSL. The only thing vaguely resembling a technician’s vehicle was a ladder attached to the roof.

The visit took place without prior notice or a scheduled date and time. Fortunately, Maria was home to let them in. The pair of technicians replaced the network cable from the pole with a thinner one. They then installed and configured the modem. Maria finally had a stable Internet connection at home again. By this point, she was exhausted. Her life had been turned upside down, with numerous classes to attend and many overdue assignments to submit.

Even with all her effort, she was unable to fulfill some demands, affecting her monthly income. However, unlike her, a significant portion of the neighborhood decided to wait for the return of Internet service from major providers. According to her, her routine was further disrupted because, upon regaining connection, she had to accommodate acquaintances and neighbors who could no longer work or study in their own homes due to the lack of service, whether from major providers or the delay and amateurism of the small company.

Maria continued working ten to twelve hours a day for the next few days to catch up. For ten uninterrupted days, she experienced long working hours, insomnia, and anxiety attacks. Her life only returned to some level of normalcy on January 27. Her work and studies were finally back on track, but her mental and physical health were not.

The story does not end here. Weeks went by, and the connection experienced abnormal fluctuations again. Whenever requested, technical support takes at least two days to be carried out. As a result, Maria spent a great part of February and March of 2023 without service. Months later, she continues to experience significant problems with the Internet.

Walking through the streets of Piedade, anyone can see that many poles have cut and entangled wires and cables. While it is true that the neighborhood’s poles were never in good shape, they have never faced such a state of degradation before. Numerous loose cables are left dangling, posing a risk to the population, along with open and raided Internet boxes.

Lack of Internet Access and Public Safety

On December 20, 2020, local news program RJTV2 aired a report on 16 companies linked to organized crime in the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region offering Internet services. The report, based on an exclusive document from the Disque Denúncia hotline, details the modus operandi of organized crime to hijack the services offered by mainstream providers. Initially, they cut cables to disrupt the signal of major service providers, always accompanied by overt threats to the employees and technicians of these companies. Subsequently, companies run by militias or drug traffickers monopolize or dominate service provision in these areas. However, it is crucial to emphasize that these services are expensive, low-quality, offer terrible customer service, and are always provided by unknown, small to medium-sized, and relatively new companies.

These companies appear to be formal businesses but function as a source of income for organized crime. The report stated that six companies are linked to militias in the West and North Zones, and Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, and that nine of them are associated with drug trafficking in the regions of Centro, North Zone, Baixada Fluminense, and São Gonçalo—both in the Greater Rio metropolitan region—and Região dos Lagos, an important lakeside and oceanfront resort area to the east of the city.

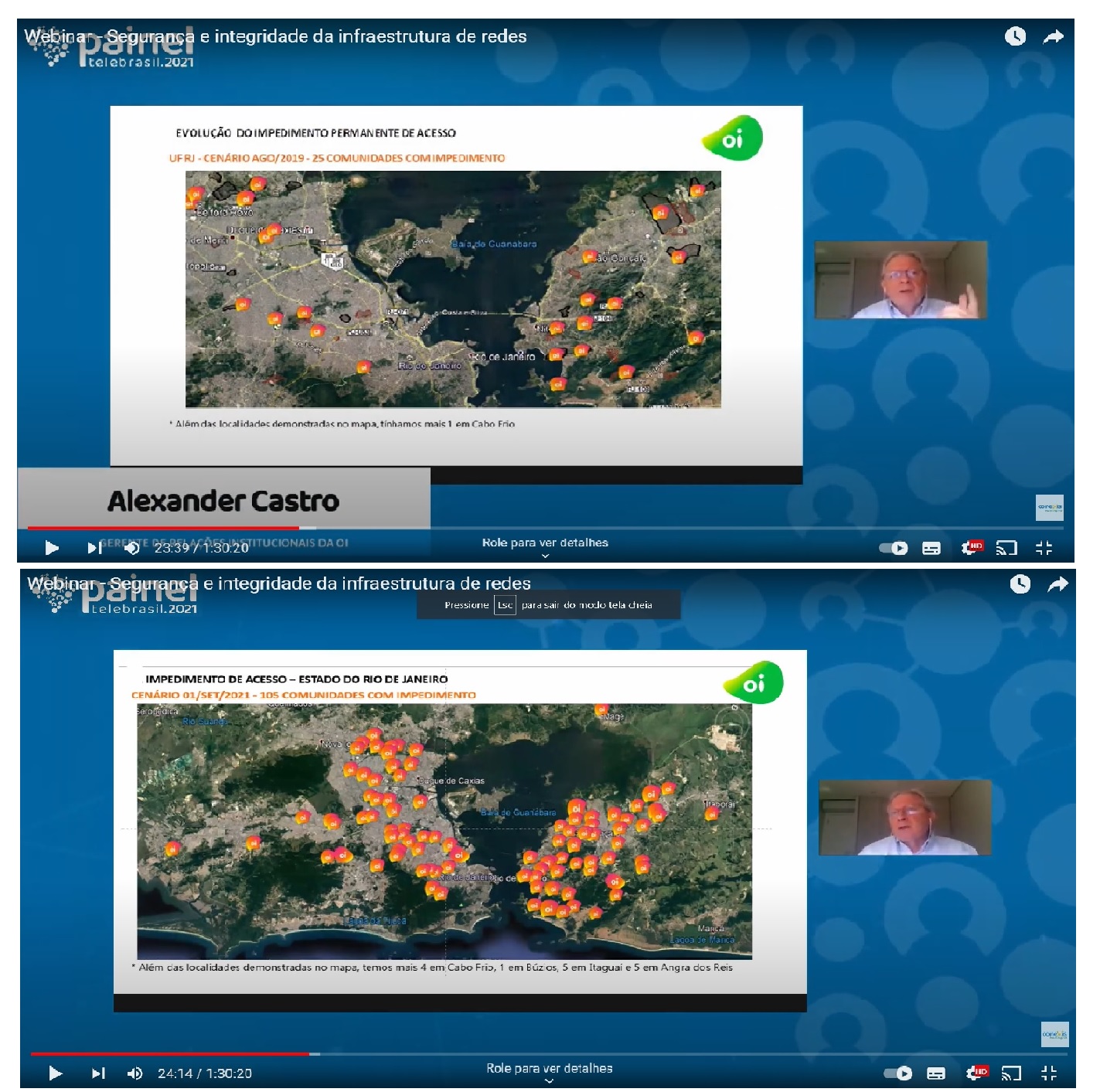

According to Conexis Brasil Digital, the entity representing the country’s largest telecommunications operators, 2.38 million meters of telecom cables were stolen or robbed in the second half of 2022. During the first half of 2023, the number increased to 2.89 million meters stolen or robbed throughout Brazil. A 2019 mapping done by Oi, one of Brazil’s major telecommunications companies, showed 25 areas controlled by drug traffickers or militias where these gangs directly interfered with telecom services. By 2020, this number had risen to 105, marking a 70% increase.

On September 13, 2022, the Civil Police, through the Department of Repression to Organized Criminal Actions (Draco-IE), carried out Operation Denied Access, executing 12 search and seizure warrants at the headquarters and branches of clandestine Internet providers in various points of the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region. In a news report published the same day by Band, it was stated that over 1,500 people were left without Internet because there were companies accused of monopolistically exploiting the service alongside the gangs that control the territory, stealing materials, damaging aerial or underground installations, and preventing the work of employees of the region’s service providers.

While this practice becomes increasingly common in the metropolis, residents of favelas and peripheries are the most affected. Cable theft and the hindrance of activities by employees of major service providers do not predominantly occur in wealthy areas of the city. Precarious workers, like Maria need the Internet to work and study. They pay a high price for poor service and have to live in fear and uncertainty, deteriorating both physically and mentally.

Months after the onset of this telecommunication crisis in Piedade, the service remains poor, with significant fluctuations and considerable delays. This harms those who depend on the Internet for work, study, and entertainment. Even in the digital world, the city remains divided. While some have easy access to broadband, others are at the mercy of precarious services.

*The interviewee’s name in the text is fictitious to preserve her identity. Joaquim da Silva is a pseudonym chosen to preserve the author’s identity.