Originally published in Portuguese in 2020, this is part two of a two-part article that describes the expansion of the state-sanctioned power of vigilante police militias in the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region. Still relevant four years later, with new municipal elections to take place, we publish the article to facilitate international understanding of Rio’s security situation. This second part provides a brief history of the militias from the military dictatorship to present day, examining their methods of infiltrating the State. Click here for part 1.

Militias are no longer merely a parallel power in Rio de Janeiro. The level of infiltration and control they hold over the State itself mean today’s militias are central to power in the state. Thus says sociologist José Cláudio Alves, professor at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ), who has studied the phenomenon for 26 years. But how can this criminal political-social situation in Rio de Janeiro be explained?

According to Alves, the influence of militias extends beyond managing black markets, reaching into the realms of political power. They have converted territorial control into political sway, whether in the legislative or executive spheres. An area under militia dominance over the years becomes an electoral stronghold. The connection between legislators and militia men is a political legacy from councilors and deputies linked to death squads from the 1990s, alongside their longstanding ties with the police.

We can see the militia’s growth as a consequence of the historical accumulation of power by extermination squads in Greater Rio de Janeiro’s Baixada Fluminense region, now expanded into several other parts of the state, emphasizes Alves. “The police have always engaged in wholesale killings, operating across many regions and targeting the poor. Regardless of the victim or the justification, [the police] kill, citing the fight against crime and the War on Drugs. This has always been the case. What we witnessed [in 2020] was a blatant exposure of this reality with Bolsonarism, transforming this rhetoric into a political agenda,” he underscores.

Militia-controlled areas also serve as a breeding ground for the emergence of leaders—among them, evangelicals linked to religious fundamentalism—who accumulate political capital in these regions. The power and consolidation of the militias result from a complex interplay of economic and social dynamics with various facets spanning decades, explains Alves. This encompasses the discourse that legitimizes violence in society with the mantra “a good criminal is a dead criminal,” to the agenda of arming the population and approving the justification of unlawfulness, ensuring police impunity in criminal cases. Meanwhile, the fragmentation of the opposition leaves adversaries unable to effectively respond to this crisis of political and social representation.

In addition to these layers and processes, José Cláudio Alves highlights the significant influence of militias within neo-Pentecostal evangelical groups in the favelas and peripheral areas. “When you take a close look at the occupants of these ministries, you’ll notice that those in influential positions today were, and continue to be, historically excluded from the dominant structures of society. The evangelicals there have always seen themselves as outcasts, pariahs of sorts. Perceived and treated as outsiders, they now identify echoes of themselves, of other ‘helpless souls like them,’ currently holding positions of power,” Alves explains.

According to him, religious fundamentalism has gained significant ground because the religious realm has become one of the few spaces where the destitute and poor population has managed to connect with a social structure for salvation. Cast “into the basin of souls” by the neoliberal State model, which eroded and dismantled social protection in areas like employment, income, housing, and urban mobility, the poorest found solace in the neo-Pentecostal churches. Moreover, these churches have come to occupy a crucial emotional role for this segment of the population in the face of the State’s dismantling.

“Gradually, everything was handed over to the private sector, placing the burden on the shoulders of the poorest—the vulnerable who have nowhere and no one to turn to. They found solace in the church,” emphasizes the UFRRJ professor.

Additionally, there are the spoils of mega-events, left by past administrations as an inheritance for the militias. They learned, both from and within the State, how to “turn the city into a big business for wealth extraction,” says Alves.

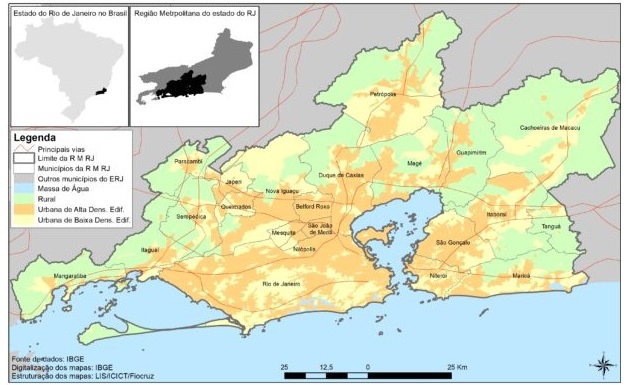

According to him, the state of Rio is currently operated by “militia geopolitics,” spreading across many parts of Greater Rio, with a particular concentration in the West Zone and municipalities of Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense, including Duque de Caxias, Japeri, Nova Iguaçu, Belford Roxo, Queimados and Seropédica. These cities are linked by the Arco Metropolitano, which connects to the Port of Itaguaí. In this dynamic, militias have also begun to operate in the North Zone, while discreetly extending their influence into the state capital’s South Zone.

Militia-controlled areas in the North Zone serve as operational centers, allowing them to organize and fight over territories with drug traffickers. Militias, allied with other criminal factions such as the Pure Third Command, have come into conflict with the Red Command.

Typically consisting of Military and Civil Police officers, as well as members of the Fire Department, militias control approximately 25.5% of Rio’s neighborhoods, totaling 57.5% of the city’s area. This data comes from a study carried out by the Fluminense Federal University’s Study Group on the New Illegalities (GENI/UFF), Fogo Cruzado, USP’s Center for the Study of Violence, news platform Pista News and crime-fighting hotline Disque-Denúncia. In addition to their presence in Rio, militias extend their control to territories and cities in the Metropolitan Region.

Today, militias are present in 15 Brazilian states. “If you look at their structures, they always act according to the logic of the wealthy in that region. So, as they move further into the countryside, militia groups collaborate with agribusinesses, large land owners, oligarchs, and mining groups,” says Alves.

Scuderie Le Cocq, CPI for Militias and Elections

In 2009, the Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CPI) on Militias led to the arrest of 246 militia men in Rio, a threefold increase from the previous year’s 78 arrests. The CPI prompted paramilitary groups to adopt a more discreet approach, described as “low-key” in a study by the Rio de Janeiro State University’s (UERJ) Laboratory for the Analysis of Violence (LAV).

However, the crackdown de-escalated after 2010, reaching its lowest point with just 55 arrests in 2013, according to a joint report by Piauí magazine and Agência Lupa. “The CPI should persist over time. While it has its merits, it is limited, being a political action restricted to the parliamentary sphere,” says Alves.

In 2019, a specialized task force from the Rio de Janeiro State Public Prosecutor’s Office dedicated to fighting militias accused 1,060 individuals and arrested 336 for their involvement with these groups. Since 2012, Brazilian legislation has defined militia activity in Article 288 of the Penal Code. However, this classification is outdated. Law 12,720 recognizes militia activities as “a crime related to the extermination of human beings,” but today’s militias are involved in a much broader spectrum of crimes. As a result, most militia wrongdoings lack adequate legal provisions.

According to a study conducted by Forum Grita Baixada, 25 people connected to politics in the Baixada Fluminense were assassinated in the 60 months preceding 2020. The Forum examined newspaper reports and websites, identifying murder cases of individuals linked to politics in the region since 2016 (the period since the previous municipal elections). The survey revealed that, between 2016 and November 10, 2020, 25 pre-candidates, candidates, public policymakers, and electoral officials were assassinated in the region.

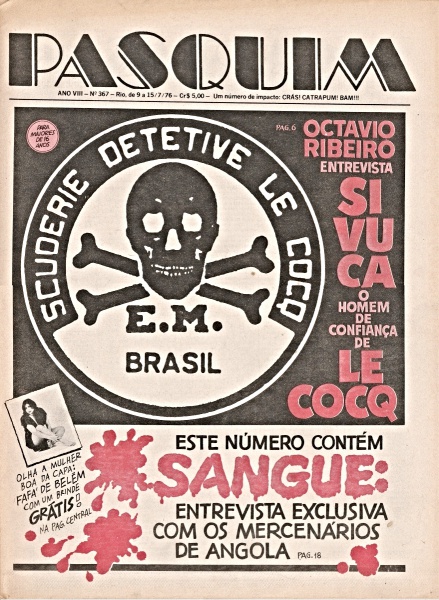

To Luiz Eduardo Soares, an anthropologist specializing in public security policy and the former National Secretary of Public Security, this militia-state has historical roots in the Scuderie Le Cocq. This death squad, composed of Rio police officers, sought to avenge the death of detective Milton Le Cocq and other police officers. Officially founded in 1984 under the guise of “improving morals and serving the community,” the group’s existence, however, traces back to the military dictatorship. In the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, their “operations” earned them the notorious label of a death squad.

“In the 1960s, Le Cocq became a ‘serpent’s egg.’ Operating mainly in the Baixada Fluminense, executing alleged criminals, they became guns-for-hire, serving local politicians for personal reasons or engaging in economic activities, functioning as professional hitmen. They were police officers, trained in torture and assassination to eliminate political opponents of the military regime. With the end of the dictatorship, however, they returned to their original battalions without ever having ceased being part of the State,” said Soares in the webinar “Militias and Electoral Capture,” organized by Foro Inteligência.

“In the 1960s, Le Cocq became a ‘serpent’s egg.’ Operating mainly in the Baixada Fluminense, executing alleged criminals, they became guns-for-hire, serving local politicians for personal reasons or engaging in economic activities, functioning as professional hitmen. They were police officers, trained in torture and assassination to eliminate political opponents of the military regime. With the end of the dictatorship, however, they returned to their original battalions without ever having ceased being part of the State,” said Soares in the webinar “Militias and Electoral Capture,” organized by Foro Inteligência.

The group also had branches in São Paulo and Vitória, in the state of Espírito Santo. Scuderie Le Cocq was dissolved in 2004 by the Federal Court following a request from the Federal Prosecutor’s Office. However, it reemerged in 2015 as the “Scuderie Detective Le Cocq Philanthropic Association,” aiming to “provide legal assistance to police accused of a crime while carrying out their duties and to advocate for the repeal of the Disarmament Statute.”

Democracy vs. Dictatorship

“In the transition to democracy, we were mediated and negotiated. We moved straight into reconciliation, sweeping our wounds under the rug. We transitioned directly into the new regime, which was inaugurated with the 1988 Constitution. The representatives of the military government who still had some influence positioned themselves in the field of public security and in organizational structures forged by the dictatorship,” says Soares.

This legacy, as Soares explains, endures. The lack of restructuring in post-dictatorship police institutions meant that several illegal procedures were left unchanged. Without this reorganization, a culture persisted within the police, regardless of the regime’s end, coexisting with democracy. “Individuals—men and women—with values and action protocols forged in the previous structure [of the dictatorship], have incorporated this model of policing as a culture and practice.”

“Public security was not affected by the transition to democracy. The past coexists, as strong, resistant, and intractable as ever, alongside the democratization of Brazilian society. It’s a paradoxical design, a dichotomy and a duality,” ponders Soares.

Soares highlights the challenge for civil society to fully grasp the severity of the militia issue, emphasizing that maintaining a “negligent and complicit silence” is no longer acceptable. In Brazil, particularly in Rio—both in the capital and across the entire state—“routine episodes of police violence” would not persist if numerous segments of society did not acquiesce to State violence.

“From a sociological standpoint this might be interesting but in practice, it’s appalling for the Brazilian people. We live in the depths of this conflict and clash, with republican institutions accepting the unacceptable and society cheering on this fascist, brutal culture. We live in a much more complex democratic culture than we can imagine; we are neither one thing nor the other,” says Soares.

Military Intervention vs. Militias

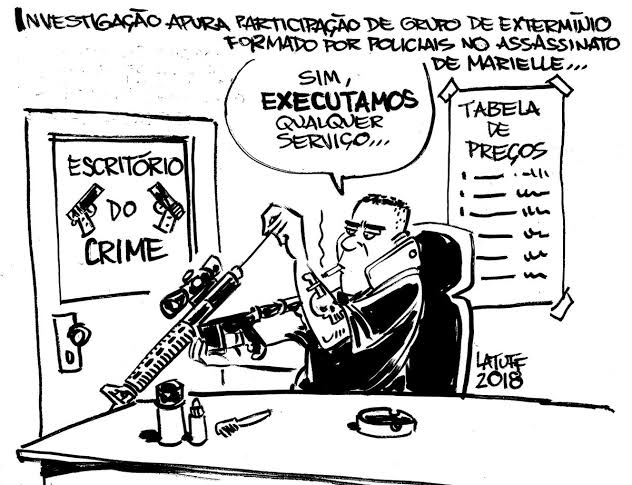

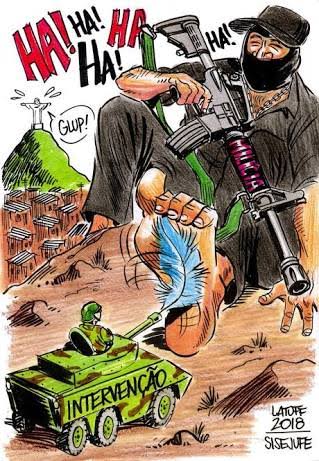

According to both Luiz Eduardo Soares and José Cláudio Alves, the 2018 federal intervention in Rio by the Armed Forces fell short of dismantling militias because the State itself serves as the backbone and enabler of these militia groups. Both scholars point to the execution of Marielle Franco on March 14, 2018—an elected councilor with over 46,000 votes, born and raised in the Maré favela complex—as a glaring example.

Soares asserts, “The Armed Forces, theoretically capable of independently safeguarding Brazilian democracy, prove both unable and, ultimately, uninterested in intervening. And if there is any semblance of independence, it hasn’t materialized in practice. The assassinations of Marielle and Anderson Gomes stand as the most chilling indicators of militia insubordination.”

“The deaths of Marielle and Anderson occurred during the federal intervention in Rio, a time when General Braga Neto, [in 2020] Brazil’s Chief of Staff, was orchestrating a political project with national aspirations. This shows that these influential figures were already in the early stages of organizing,” says Alves.

“The deaths of Marielle and Anderson occurred during the federal intervention in Rio, a time when General Braga Neto, [in 2020] Brazil’s Chief of Staff, was orchestrating a political project with national aspirations. This shows that these influential figures were already in the early stages of organizing,” says Alves.

“Marielle’s case still hasn’t come to light in full. The military intervention failed to unearth the full extent of this crime, crucial to the city’s history and social justice,” he continued.

[During the 2020 interview] Alves asserted that, “Brazil is living an anti-democracy disguised as democracy—deceiving and imprisoning everyone in a charade. Bound to this conception of democracy, as we open a door expecting a garden of rights, we find ourselves unlocking the doors to a basement full of skeletons.”

With a series of setbacks, the investigation into the assassination of Marielle Franco and her driver Anderson Gomes dragged on for years without a clear resolution. While two individuals had been accused of carrying out the crime, the motivations behind it and the identities of those who orchestrated it remained elusive [until March 2024]. According to the investigation, the councilor’s death is linked to militia groups associated with the Crime Bureau.

This is part two of a two-part article that described the expansion of militias as part of State power in Greater Rio de Janeiro in 2020, but still relevant prior to municipal elections of 2024. Click here for part 1.