Clique aqui para Português

A Brazilian Literary Classic

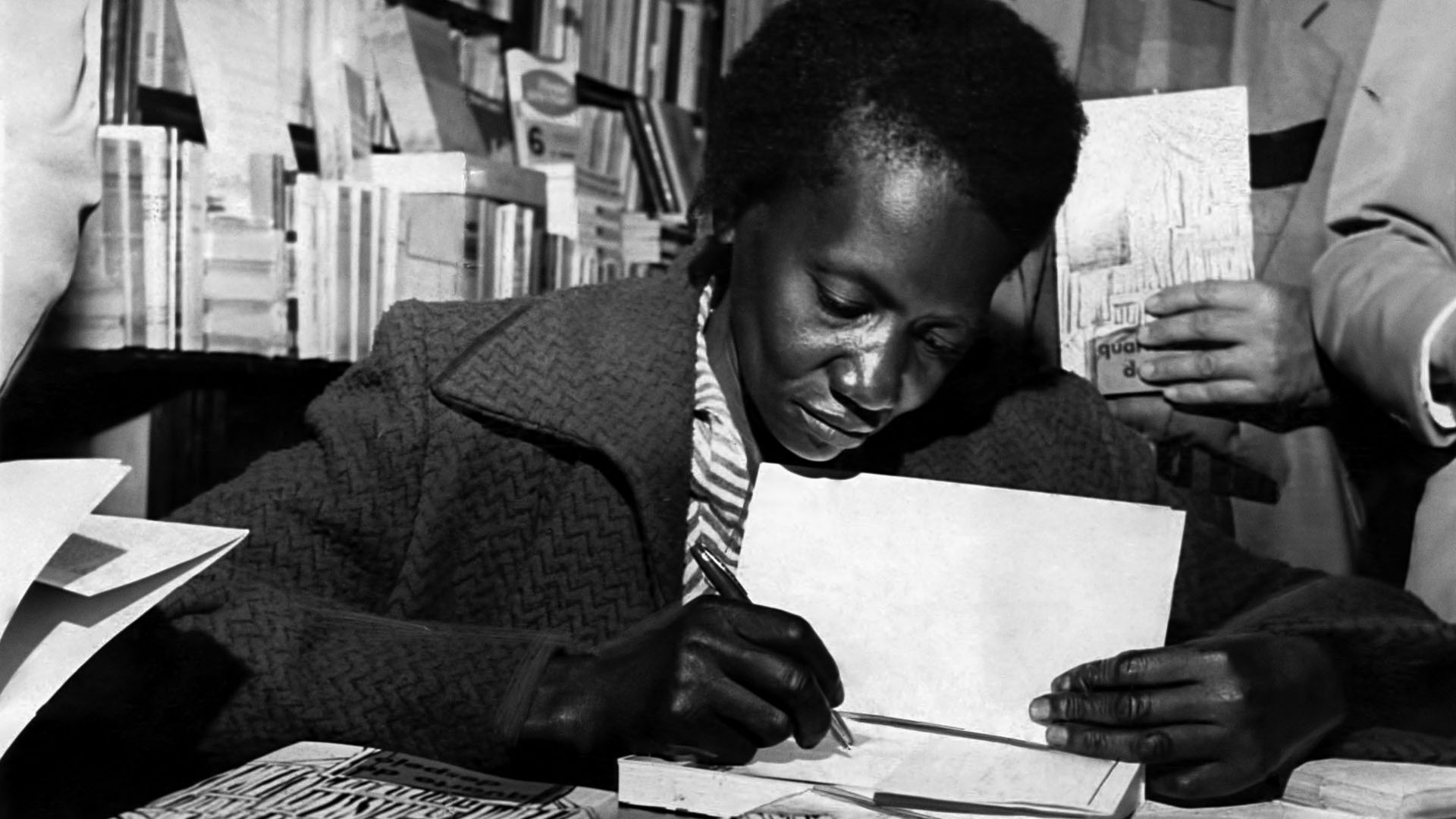

Carolina Maria de Jesus said so much about Brazil. Her writing, charged with feeling and indignation, reflected a difficult reality not only experienced by the writer herself, decades ago, but by millions of Brazilians even today. Her works are documents that bear witness to the resistance of a Black woman from the favela. Leaving the countryside in her home state of Minas Gerais, she moved to Favela do Canindé in central São Paulo, from where her literary and poetic works earned their place in Brazil’s literary canon and in the ongoing fight against racism. She also made significant contributions to the national socioeconomic debate.

Carolina Maria de Jesus’ contributions still inspires the emergence of new Black intellectuals from peripheral neighborhoods, such as Marcelle Leal, a Black woman raised in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone neighborhood of Bento Ribeiro, a scholar on Carolina Maria de Jesus and PhD in Literary Theory from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). She studies the writer’s travels in South America, as well as feminism and Black Brazilian literature. According to Leal, just as Carolina Maria de Jesus demonstrates in her work: “racism, extreme poverty, and inequality cannot be normalized.” For Leal, this is one of the most valuable contributions by de Jesus, the most consequential author on Brazilian socioeconomic thought.

Because of her impact, the Carolina Maria de Jesus: Brazil for Brazilians exhibition was opened to the public in late 2023 at the Rio Art Museum (MAR). The exhibition told the story of the writer and how her work forever changed Brazil.

Her best-known book, Quarto de Despejo (published in English as Child of the Dark and considered a literary classic), has been translated into 13 languages. The book features her experiences as a Black woman living in a favela dealing with the challenges she faced in supporting her family, and her worldview.

“Child of the Dark is a work that allows us to understand Brazil from the perspective of those who experience the country in its most vivid capacity.” — Marcelle Leal

Socioeconomic Lessons From Carolina Maria de Jesus

“Unfortunately, racism follows her to this day. We must remember that there is still inadequate organization and preservation of her writings. Some of her original works are still scattered around the world or under the tutelage of people who improperly appropriate her collection of works. Society insists on determining the place it reserves for Black people, but, in individual and collective movements, there are resistances and subversions, just like Carolina.” — Marcelle Leal

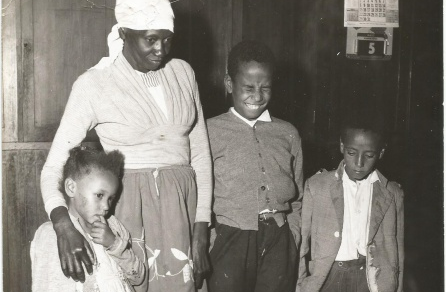

There are still many Carolinas throughout Brazil: Black favela mothers, subjected to a burdensome, centuries-long culture that is conditioned to limit their place in society. These women are forced to fight for public policies that support them, despite being the largest demographic and constituting the economic and social foundation of Brazil.

“Actually, the world is the way the whites want it. I’m not white, so I don’t have anything to do with this disorganized world.” — Child of the Dark, by Carolina Maria de Jesus, translation by David St. Clair

Leal highlights an excerpt from Carolina Maria de Jesus’ writing in which she analyzes her own suffering as a woman that is Black, impoverished, and a single mother: “I put the sack on my head and the weight of Vera Eunice in my arms. Sometimes it makes me angry. Then I get ahold of myself. She’s not guilty because she’s in this world,” says the author in her book. An analytical account that is not only about her situation but about millions of Brazilian women like her, who come alive through her words.

Carolina Maria de Jesus’ perception—stemming from her position as a Black woman and mother living in a favela—renders her work to this day one of the most substantial theoretical frameworks available on Brazilian society and Black women. Half a century after Brazil formally abolished slavery, written in the 1930s, her anthology still educates a nation about the plight of Black women and men: the ills of material poverty, hunger, their denied right to housing, as well as the resilience, intellect, and strength of the Afro-Diasporic woman. In sum, Carolina Maria de Jesus educates Brazilians about Brazil.

Poor Innocent

A mother wanders, oppressed,

Eyes cast low,

How can life progress,

In this racial undertow…She casts a glance around,

Then once again to the ground,

All the while gently caressing,

The child in her arms, her sweet blessing.Poor woman, where do you go?

This cruel fate, it hurts you so

I search for papa

My good friend from before…All my life I roam in lament

My existence, a constant struggle

I pray to God, so good and clement

For only he will bother…Where do we go, my boy?

No roof above, no bread to enjoy.

Your father’s absence, a cruel ploy,

Leaving you alone, my precious joy…Why, child, must you endure such pain?

When among the sinless, you remain.

If death were to call my name,

You’d be left alone, helpless, and shamed.Without someone to watch over your path,

With affection and sacrifices,

You will fall into the traps,

That are life’s worst vices.Still wandering, the mother,

As her mind these thoughts smother

Looks at her child and in tears, she exclaims:

poor innocent!— Personal Anthology, Carolina Maria de Jesus [No official English translation found; poem translated by Claudia Guimarães for RioOnWatch]

Leal emphasizes the need to support Black and favela mothers through legislation, public policy, and budgetary measures. The scholar believes we must offer spaces in public daycare centers, and establish facilities to welcome and care for the children of parents who work or study outside regular daycare hours, as proposed in the Owl Space Law by Marielle Franco, a Black councilwoman born and raised in Rio’s favelas who was the victim of a political assassination six years ago. These measures would complement conditional cash transfer social programs like Bolsa Familia and efforts to increase access to schools, universities, and the job market in a way that upholds their dignity. Furthermore, it is essential that Black intellectuals, like Carolina Maria de Jesus, are read and studied across Brazil.

The contributions made by the writer to the ongoing racial and socioeconomic debate in Brazil are quite significant.

“Social vulnerability needs to be combated by public authorities and not just used as fodder for charity from the private sector. Carolina Maria de Jesus brings to the forefront of the debate the collective shadows that, over many years, Brazil insisted on sweeping under the rug. Socioeconomic discussions are present in her work, as described in her diaries, depicting the city as the living room and the favela as the ‘junk room,’ where racial issues are also intertwined. Furthermore, she exposes the situation of the country’s Black community.” — Marcelle Leal

According to Leal, though de Jesus made significant contributions to Brazil, the sad reality of her literary erasure is due to racism, classism, and sexism in the publishing world, which is primarily composed of white, middle-class men with university degrees, who are blind to its importance.

“[It’s necessary] to rework these limits so that this art is not restricted within the domain of a minority but is composed in a broad, inclusive, and pluralistic manner. The challenge lies not only in production but also in cultivating a readership and technical expertise in addition to dissemination. I insist, once again, on fighting for policies that grant access to education and culture, as well as financial support, because these resources are still concentrated in the hands of a few and are fundamental to making the movement happen. We’ve made progress compared to decades ago, but there’s still a lot to achieve.” — Marcelle Leal

At the end of the interview, Marcelle Leal quotes an untitled poem by de Jesus, published as the prologue to the chapter “Diaries in the Junk Room” in the book The Unedited Diaries of Carolina Maria de Jesus (originally published in Portuguese as Meu Estranho Diário). According to the scholar, this excerpt is foundational, as it clearly states de Jesus’ thoughts on race, racism, and anti-racism, in addition to summarizing Black people’s social position in post-abolition Brazil.

Untitled

When they saw me many fled

Supposing I took no note,

Others asked to have a read,

At the verses that I wrote.It was paper that I collected

To finance my living needs.

In the garbage I resurrected

Many books for me to read.

So many things I wished to do

But prejudice checked my tracks

If I die I want to be born anew

In a country run by Blacks.Farewell, Goodbye! I am going to die!

And these verses I leave to my country

If I have the right to be once more alive

With happy Blacks I will find me.— The Unedited Diaries of Carolina Maria de Jesus, organized by Robert M. Levine and José Carlos Sebe Bom Meihy; translated by Nany Naro and Cristina Mehrtens

About the author: Igor Soares is a journalist with a degree from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). He is currently a homepage writer for Portal iG, contributes to #Colabora, and works as a freelancer. He has experience in covering cities, human rights, and public security, having previously worked at Estadão and produced reports for Folha de São Paulo.