This article is part of a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on environmental justice in the favelas for RioOnWatch.

This article is part of a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on environmental justice in the favelas for RioOnWatch.

Otávio Barros, a fifth generation resident of the small favela of Vale Encantado, located in the buffer area surrounding Rio de Janeiro’s Tijuca Forest, was elected president of the community’s residents’ association in 2005. Soon after, in 2007, he founded the Vale Encantado Cooperative, with nearly two dozen neighbors, to generate eco-friendly employment for their families. Among other activities that build on the community’s vocation for sustainability is a guided tour through the community and surrounding forest, followed by a multi-course lunch featuring their eco-gastronomy.

Barros takes visitors along paths in the forest, introducing them to plants they will be eating shortly thereafter. One that stands out is jackfruit, the world’s largest tree-borne fruit, originally from Asia and historically stigmatized in Brazil.

The jackfruit trees near the community are tall and old. In Brazil, jackfruit trees have two fruiting seasons, and fruits can weigh up to 80 pounds.

Vale Encantado’s restaurant, alongside a growing movement of other community kitchens like Babilônia’s Favela Orgânica, advocacy organizations like Mão na Jaca (Hands on Jackfruit), and favela agroforestry projects producing and selling jackfruit, like CEM, are working to challenge the stigma around jackfruit and promote it as the extremely rich food source that it is. Jackfruit, as a signature ingredient in their gastronomy, allows residents to achieve greater economic and food security.

Jackfruit as a Colonial Commodity

According to the historical record, Portuguese colonists brought jackfruit to Brazil in the late 17th century—namely to Salvador, Bahia, colonial Brazil’s first capital. Encountering the fruit in India, they most likely transported it from Goa, a Portuguese stronghold on the country’s western coast. At the time, the Portuguese were embarking on a globe-spanning project of botanical experimentation, transplanting species between various tropical colonies.

“Once it got here, it just blossomed. It really loved the soil and weather,” explains Alexandro Solórzano, a professor of geography at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio) who has been mapping jackfruit’s distribution in the Atlantic Forest for the past ten years.

One of the most widely circulated early Portuguese accounts of the fruit is the physician Garcia de Orta’s 16th-century treatise Colloquies on the Simples and Drugs of India. He wrote, “It is dark green and all surrounded by spines smaller than those of the hedgehog, but they do not prick as those do,” and documented people drying, boiling, and roasting pieces of the fruit in India. The Portuguese word “jaca” likely comes from the Malayalam word “chakka,” which de Orta transcribed as “jaca.”

But jackfruit was also intertwined with the trade in enslaved people and developed racialized connotations. It is probable that the fruit arrived on ships that the Portuguese used for trafficking enslaved Africans. Its global distribution also tracks on to Portuguese ports in Africa, such as Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, and São Tome and Principe. Once enslaved Africans reached Brazil, slave holders considered it a cheap and convenient food source for feeding their workers and promoted it as a quick solution to famine and hunger. After the abolition of slavery in Brazil, jackfruit lingered as a strategy to enable food security among the most socially vulnerable Brazilians.

Solórzano said that, even now, “it’s still connected to Black people.” In his opinion, there are clear remnants of this link in Brazil when, for instance, “jackfruit is called ‘fruit of poor people.’”

Only the fruit was transported across oceans; local Asian knowledge of how to prepare it was not. The jackfruit tree ties together distant lands, joining them in shared history, even if the context and the understanding of its uses was lost along the way. “I imagine that because [this knowledge] didn’t come—this recipe book, so to speak—[the fruit] wasn’t really valued,” Solórzano said.

Redefining Jackfruit through Gastronomy in the Favela

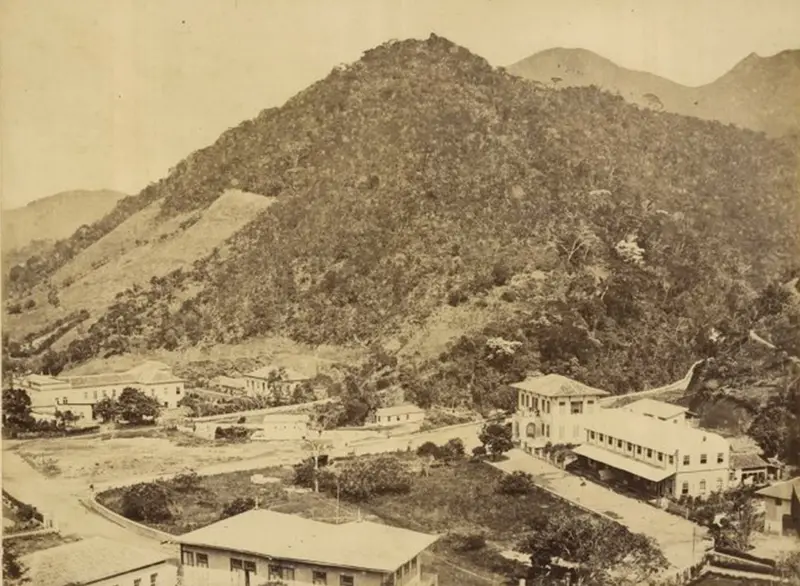

Today, jackfruit trees stretch their canopies above the forest that surrounds Vale Encantado. The community occupies a small nook in the hills of Alto da Boa Vista, an affluent area which nonetheless includes a number of small favelas. Most of Vale’s residents have lived here for generations.

Towards the end of Barros’ tour along the forest trail, he shows a group the community’s sewage bio-system, then leads them up to the grand finale of the tour: at the coop’s restaurant, visitors enjoy a meal prepared by women members who use the kitchen’s own biodigester-generated biogas to cook their signature dishes.

The main course is bobó, an Afro-Brazilian stew generally made of shrimp, but that, in Vale’s vegan version is made of jackfruit. It is creamy, full-bodied yet fresh. The base of cassava, coconut milk, and tomato gives way to the floral taste of jackfruit, which Barros says he easily collected from the forest that morning—to visitors’ amusement—due to a supportive monkey. Paired with coconut-flecked rice, it goes down easily.

Vale Encantado began preparing foods with jackfruit around 2005. The women chefs use it to make desserts, such as jackfruit sweet bread and sorbet. They also use it as a substitute in traditional Brazilian dishes, making jacalhau, a jackfruit-based rendition of a traditional Portuguese codfish dish; bolinho de jacalhau, a fried jackfruit ball that also plays on the codfish original; coxinha de jaca, a fried snack; jackfruit stroganoff; empadinha de jaca, small jackfruit empanadas; moqueca, an Afro-Brazilian seafood-based stew; and ensopadinho de jaca or jackfruit soup.

These jackfruit-related Vale Encantado culinary innovations are produced by four women who work in the cooperative kitchen: Rozineida Pereira Machado, Madalena Medeiros, and Cátia Medeiros dos Santos and her daughter, Bruna dos Santos, who occasionally helps, but mainly focuses on managing the reception.

“We also do research into various dishes on the Internet. I’ve seen videos of how jackfruit is used in India.” — Otávio Barros

Jackfruit can be found in Rio de Janeiro’s bountiful produce markets, but is one of the rarer items. “Here, in Vale, we have a lot. So the cost-benefit is that we have to go to the market to buy other things to make, but we find jackfruit here,” Barros says. He acknowledges, “People are still prejudiced about working with jackfruit and making dishes with jackfruit.”

Jackfruit as a Clue into Interconnected Histories

As a non-native fruit, coming from another part of the world, jackfruit is widely considered an invasive species, which adds to its stigma in Brazil. Through his research, however, Solórzano has uncovered new information about its history in Rio. “The notion of jackfruit that had come to me was that it was an exotic species, potentially invasive,” he said. “It was invading the Atlantic Forest, it was repressing the [endemic] vegetation.”

However, through his data collection, Solórzano came to a different conclusion: “My hypothesis is that [rather than] an invasive species, [what characterizes jackfruit here is that it is] a bio-cultural indicator of where there was human presence.”

During the 1800s, Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro II decided to reforest the Tijuca Forest, in order to recover the water supply serving Rio. Coffee monocropping in the region had brought drought to the city.

While looking at jackfruit distribution in the Tijuca Forest, Solórzano and his team found a fascinating correlation with charcoal production sites.

“It was not just jackfruit that we had to measure [in the forest]. We had to measure jackfruit, charcoal, and ruins of old houses, old farms, you name it. That’s when we started to map what we call social-ecological legacies, which are legacies of past human use on landscapes.” — Alexandro Solórzano

In other words, jackfruit locations hold clues into the lives of the people who lived or worked in the forest, on the margins of the city, namely enslaved Afro-Brazilians and their descendants. Moreover, some of these were from quilombos, villages of formerly enslaved people, and their descendants.

The statistics they gathered were staggering. Charcoal distribution overlaid with jackfruit distribution accounts for 50% of the total jackfruit presence. And then: “When you overlay the trails and the old paths and the ruins of the houses and the bridges, when you sum all that influence, it explains more than 90%.”

While demonstrating the relationship between jackfruit and charcoal production, near a grove of jackfruit trees adjacent to the community of Horto, Solórzano scratches the ground and the soil changes from a dusty brown to a rich black. The black color is evidence of charcoal—and he casually reaches down to pick up chips of charcoal that lie essentially on the surface.

These chips are remnants of when producers would burn forest biomass in clay furnaces to create charcoal. Solórzano mentions that the age of some of the trees indicates that producers carefully managed the forest, rather than indiscriminately extracting from it. They would focus on the smaller trees, leaving the larger ones alone. After all, they also ate jackfruit.

These trees tell a story. To some, as an invasive, exotic species, they should be removed. But to others such as Solórzano, extracting the jackfruit trees under presumption of invasiveness would be to ignore the nature of the past itself and the trees’ social, cultural, and dietary importance to Rio’s most vulnerable populations throughout history.

One of Solórzano’s students wrote a thesis on the favela of Parque da Cidade, which borders the forest. During his research, he heard about enslaved people marking the trails between it and Rocinha with jackfruit seeds, so as not to lose their way.

“Black populations were and still are very important ecological stewards of landscape… They learned how to manage all of the flora that was available to them, that also in some way would help them with their livelihoods.” — Alexandro Solórzano

It is evident that this history persists throughout the Tijuca National Park, from Horto to Vale Encantado.

Colonial Legacies in Science and Conservation

According to Solórzano, about 60% of conservationists believe that jackfruit has no place in Brazil. Others, however, hold that people and nature are and have always been interconnected and in flux, and that jackfruit has a place in Brazil.

While Solórzano acknowledges that some new species may harm ecosystems and require management, he believes that jackfruit is not among them.

The coexistence between transplanted and local species is known as a novel ecosystem. Some defenders of novel ecosystems question the vocabulary of “exotic,” “invasive” and “native” as connected to racial tropes and classification. The overlapping language hints at how ideas of difference about humans and nature were constructed at the same time, continuing to have an effect today.

Jackfruit spread so naturally in Brazil that, despite abundant records of its early presence in India, it was first classified as Artocarpus brasiliensis with the understanding that it was native to Brazil. Only later did scientists realize it was not, and change its scientific name to Artocarpus heterophyllus.

In 2014, Marisa Furtado de Oliveira founded Mão na Jaca (“Hands on Jackfruit”)—a positive spin on pé na jaca (“foot on the jackfruit”), a negative expression in Brazil that suggests getting yourself in a mess. The organization collects and donates jackfruit, teaches people how to cook it, and builds a network of proponents. Since its founding, they have donated 12.5 tons of jackfruit to vulnerable populations in Rio, according to Oliveira. Mão na Jaca partners with Vale Encantado and collaborates with Solórzano.

“When I started researching it, I discovered that there were a lot of indications that jackfruit was brought to Brazil to feed the enslaved. And when I discovered this I began to understand why jackfruit was invisible on the market, and was not welcome in many places.” — Marisa Furtado de Oliveira

In Brazil, colonizers criminalized the religions and cultures of enslaved Africans and their descendants. And this legacy remains. Jackfruit is associated with the Candomblé myth of Apaoká, one of the many ancestral women and mothers in African tradition. According to this myth, Bambá, one of three sisters who made a pact never to have children, broke the pact and had a child with Orisá Okò, the Lord of Agriculture. After this, she went to live in a sacred African mahogany tree and was renamed Apaoká like the tree, meaning “in every tree”—suggesting she became the mistress of sacred trees. When believers were brought to Brazil, they found no African mahogany but saw the same majesty and resilience in the jackfruit tree, and incoporated its leaves into rites instead of those of the Apaoká. As a system of knowledge with Yoruba roots and traditions, Candomblé has incorporated new, foreign elements to survive and thrive over time. Thus, even this Asian tree became part of its sacred pantheon.

Solórzano aims to honor this knowledge system, emphasizing how jackfruit builds cultural resistance and resilience through the provision of food security. In addition, because of the size of the trees and fruit, it can sequester large amounts of carbon, making it a useful tool for combating climate change. Finally, by growing in degraded soil, it helps restore green cover in deforested areas.

Carving Out a Sustainable Future with Jackfruit

Jackfruit is growing in popularity in Brazil today as a meat substitute. Across the world, however, jackfruit is not a substitute, but rather a staple. In Asia, jackfruit dishes embrace style and versatility in preparation. In Brazil, it was historically eaten ripe or in a sweet dessert, but Vale Encantado and other producers of eco-gastronomy show that these are not the only options.

Katie Weintraub, a former student of Solórzano and a Mão na Jaca collaborator, is another advocate for jackfruit. She works with Sinal do Vale, an initiative focused on sustainable ecosystems located in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region. They emphasize the sustainable management of jackfruit trees in the region, particularly through using unripe green jackfruit in recipes.

“People are always shocked and amazed, especially the people who haven’t eaten green jackfruit. They’ll eat the lasagna and think it’s chicken, they’ll eat the ceviche and think it’s fish,” she said. They also use it in kibe, a food that arrived with Arab immigrants to Brazil in the early 20th century.

“In ten, twenty years, we don’t know how easy it will be to grow rice, to grow soybeans, to grow commodities, cash crops. It’s really important to be looking to the future, and we already have a great answer.” — Katie Weintraub

Weintraub has been working with nutritionists to add green jackfruit to public school menus. “We’re trying to take stuff from their existing menu and create new [recipes]. They have risotto with chicken, then the idea is that we would do risotto with jackfruit.” They plan to roll out the pilot by October.