This article is part of a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on environmental justice in the favelas for RioOnWatch. It is also part of RioOnWatch’s ongoing #VoicesFromSocialMedia series, which compiles perspectives posted on social media by favela residents and activists about events and societal themes that arise.

This article is part of a series created in partnership with the Behner Stiefel Center for Brazilian Studies at San Diego State University, to produce articles for the Digital Brazil Project on environmental justice in the favelas for RioOnWatch. It is also part of RioOnWatch’s ongoing #VoicesFromSocialMedia series, which compiles perspectives posted on social media by favela residents and activists about events and societal themes that arise.

2024 has seen a surge in devastating wildfires across Brazil, breaking alarming records and threatening nearly all of the country’s diverse biomes. September 2024 recorded the highest average number of fires for the month in the historical series, also marking the driest month in Rio de Janeiro in the last 27 years. In the Amazon, the dry season—which typically runs from May to September—has felt the cumulative impact of two consecutive years of extreme drought. At the beginning of October in São Paulo, where the rainy season should already have started, forest fires surged by 648%. As a whole, from January to October 2024, Brazil saw a 73% increase in wildfires. During the driest period of the year, usually the peak of fire activity, there was a 104% increase compared to the same period in 2023.

Most of the wildfires spreading across Brazil are caused by arson, stemming from human activity. This is the conclusion of Dr. Renata Libonati, a geoscientist and head of the Laboratory for Environmental Satellite Applications (Lasa) at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). In an interview with Agência Brasil, she stated that:

“The occurrence of wildfires in Brazil is closely tied to land use… Our current lifestyle is incompatible with the future well-being of our society.”

The toxic smoke from illegal fires across different Brazilian biomes, including the Amazon, the Cerrado, and the Pantanal regions, not only spread over the Central-West Region, as it usually does this time of year, but also covered the rest of the country, forcing everyone to breathe polluted air.

Similarly, parts of Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay have also been exposed to poor air quality. Smoke from wildfires is being carried by air currents, commonly known as “flying rivers,” which typically establish the conditions for rain and humidity in central South America, sustaining the floodplain forests of the Pantanal and the humid forests of the Atlantic Forest.

As it enters the “flying rivers” and replaces the water vapor that would normally bring rain, smoke is first blown westward until it hits the Andes Mountains, then shifts south-southeast, contaminating the air of South America’s largest cities, such as São Paulo, Buenos Aires, Brasília, Montevideo, Asunción, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, and Rio de Janeiro. In these areas, similar environmental conditions—dry weather, drought, and above-average temperatures—also trigger fires and increase air toxicity across most of the subcontinent.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Rio de Janeiro in Flames

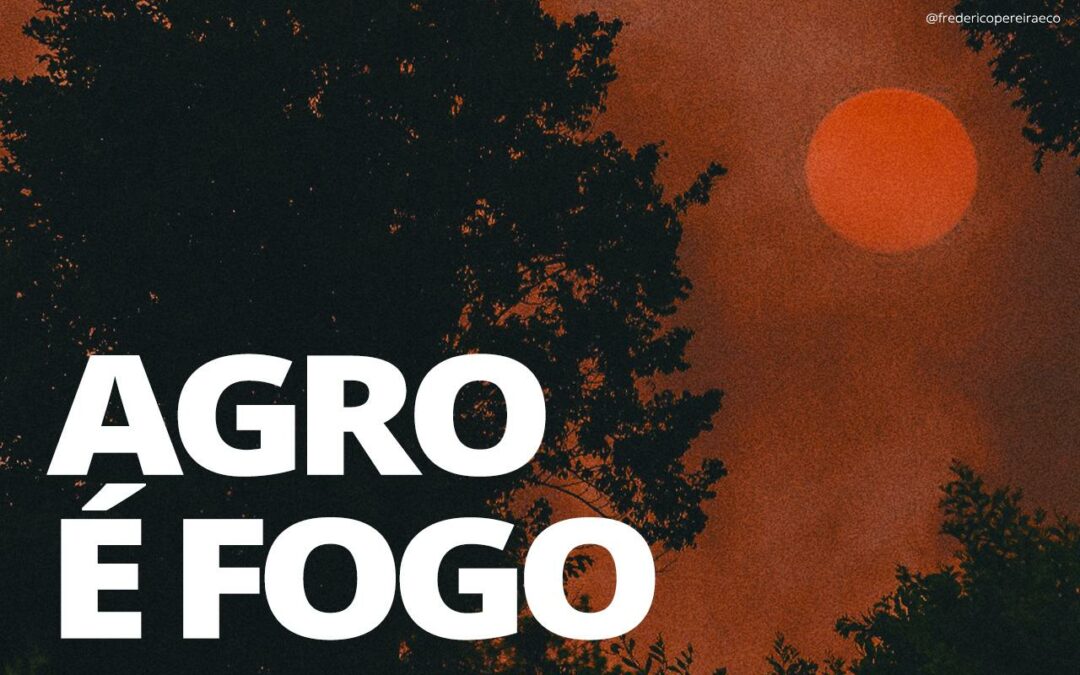

The population of the state of Rio de Janeiro has also witnessed fires devastate its landscapes. With a red sun glowing for weeks and deprived of the typical blue spring skies, Greater Rio was the most affected region in the state. The cities of Rio de Janeiro, São Gonçalo, and Duque de Caxias recorded the highest number of fires in the state. Municipalities in the rural area were also hit by wildfires and arson.

The reporting platform Portal Grande Tijuca has been documenting a series of fires in the favelas of Tijuca, located in Rio’s North Zone. On September 10, a fire broke out in the forested area of Morro dos Macacos, in Vila Isabel, but fortunately, no residents were injured.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

The same news platform reported another fire in Greater Tijuca in October, this time in Morro da Formiga. In one of the videos, a firefighter helicopter can be seen dropping water to contain the fire in the forested area of the favela.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Sumaré Hill, also part of the Tijuca Massif and located within Tijuca National Park, the largest urban forest in the world, burned persistently, frightening residents in the region. For over 24 hours, the fire department tried to control the flames using all available resources, including helicopters. Toxic smoke spread across parts of Tijuca. As the wind carried the smoke southwest, it heavily impacted the health of residents in the favelas of Salgueiro, Borel, and Formiga. Even Turano, located northeast of the fire and mostly in the opposing wind direction, experienced a decline in air quality.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

In the North Zone’s Complexo do Alemão—and in most of Rio’s favelas—waste management, which is the city’s responsibility through municipal garbage utility Comlurb, is a serious public health issue. Due to long-standing neglect by the State and irregular collection services, residents are forced to manage their garbage on their own. For some, especially those living in the higher parts of the favelas, burning waste seems like the only way to prevent it from piling up.

In times of extreme drought and dry conditions, however, the destructive potential of this practice becomes immense due to the surrounding dry vegetation. This is what happened in Pedra do Sapo in August. In a tragic incident, Dona Altamira Lourenço da Silva, 65, saw her house completely destroyed by the fire. Fortunately, she escaped unharmed with the help of her neighbors.

Another area of Complexo do Alemão that faced fires in mid-September was Matinha, located in the Serra da Misericórdia region, a forested area that connects Complexo do Alemão with Complexo da Penha. The flames started in the morning and quickly spread, putting hundreds of residents and homes at risk. Despite the lack of water, with no supply from water utility Águas do Rio for three days, residents decided to use all the water they had been saving to fight the fire—a process that took hours.

In downtown Rio, a fire burned the forested area at the base of Morro do Fogueteiro, located in the neighborhood of Santa Teresa, on September 25. There are no reports of fatalities, injuries, or houses damaged by the flames.

On the following day, in the same area, another fire put residents’ lives at risk. This time, it happened in Morro do Querosene, a community in Complexo de São Carlos, in the neighborhood of Rio Comprido. The fire hit the wooded area at the base of the hill, destroying two houses.

The situation became so concerning that, in September, the State Environmental Institute (INEA) ordered the closure of Rio de Janeiro’s state parks and conservation areas as a safety measure. Municipal parks in the city of Rio de Janeiro also faced a real trial by fire. This was the case for Prainha Natural Municipal Park, in Recreio dos Bandeirantes, in the West Zone, which was threatened by advancing flames in the same month.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Also in the Prainha region, the platform Realengo TV reported on a large-scale fire in the woods of Grumari.

Niterói was yet another city that saw its parks burn. The City Forest Park suffered fires that destroyed part of the forest on Morro das Andorinhas. A joint effort by the fire departments of the Charitas and Itaipu neighborhoods was required to control the flames, which were only contained after 24 hours. Residents filmed potential suspects setting fire to the forest, and the Civil Police are still investigating the case.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

One of the most haunting and impactful images from this devastating fire season in Rio de Janeiro came from the Tinguá Biological Reserve, in the city of Nova Iguaçu, located in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region. An INEA park guard shared a photograph of a completely charred sloth. In the same post, the account encouraged people to report anyone suspected of setting fire to the forests.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Similarly, fires have also devastated other areas of the state, with impacts no less severe. For example, Nova Friburgo—a city known for attracting tourists with its cool temperatures—was not spared from the above-average heat and fires. The Facebook page Nova Friburgo em Foco highlighted the flames that spread across a hill in the city, with residents also posting about the incident.

As a whole, in 2024, the state of Rio has registered the highest number of fires since 2017, with most of them linked to arson. By September 20, the Civil Police had already identified 34 perpetrators, but much more remains to be investigated.

The Amazon, Pantanal, and other Biomes in Flames

At the end of August, a viral video showed the fire reaching the Ytu Aldeia in the Apiaka Kaiabi Munduruku Indigenous Territory, in the Amazon region of Mato Grosso. One of the firefighters on-site filmed the tragic scenes of families fleeing the flames, carrying only the clothes on their backs and what they could hold in their hands. In his post, he criticized the precarious infrastructure available to the fire crews and the lack of personnel to fight the fires.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Concerned about the lives of indigenous Brazilians and the criminal use of fire as a tool for displacing communities and land grabbing, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) reported agribusiness for the fires. The indigenous movement demands an investigation, accountability for those responsible, and measures to mitigate the damages caused.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

Community media outlets reporting on Rio’s favelas, such as Voz das Comunidades, have also denounced the role of agribusiness in the widespread fires that hit Brazil in recent months. Similarly subjected to the logic of environmental racism, just like Brazilians in the Northern region, grassroots communicators from Rio’s favelas also understand the importance of preserving the Amazon and keeping the forest standing.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

It is important to highlight that indigenous peoples in Brazil are the primary caretakers of the Amazon Rainforest, the Atlantic Forest, the Cerrado, the Pantanal, and the Caatinga. Brazil is already experiencing temperatures above the predicted average, and it is no coincidence that the areas most affected by record temperatures, droughts, fires, and poor air quality are also those facing intense deforestation and growing interests in agribusiness expansion and illegal mining.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

This undeniable correlation between agribusiness, rising temperatures, recurring droughts, and forest fires led Judge Flávio Dino, of the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF), to raise the discussion about expropriating lands affected by deforestation and arson. According to the supreme court judge, there should be a broader interpretation of Article 243 of the Brazilian Federal Constitution. The article states that rural and urban properties where “illegal crops” or slave labor exploitation are found must be expropriated and allocated to agrarian reform and social housing programs. Dino argues that enforcing Article 243 in the fight against fires could be an effective tool, as it removes land from the hands of those responsible for the fires and places it under the care of agrarian reform, family farming, and social housing programs—options that tend to foster much healthier relationships with natural resources and the land.

About the author: Euro Mascarenhas Filho is a grassroots journalist, contributor to the Paratininga Communications Center, and creator of the Antena Aberta podcast.