The history of the city of Rio de Janeiro is marked by experiments in segregationist housing policies, which intensified during the Military Dictatorship (1964–1985). Over the course of those decades, the regime promoted the relocation of favela residents and mass evictions of communities from the city’s central areas. Those who were forcibly evicted were relocated along the path of the city’s most distant railway line: towards Santa Cruz Station.

The population forced to migrate found themselves in a rural Santa Cruz, in an agricultural West Zone. In the 1980s, the city was going through yet another wave of development, still rooted in hygienist ideals, with no real commitment to dignity or basic rights.

It was in this context that construction began on what would, for a time, become the largest housing complex in South America: Cesarão, inaugurated in May 1981, still during the Military Dictatorship.

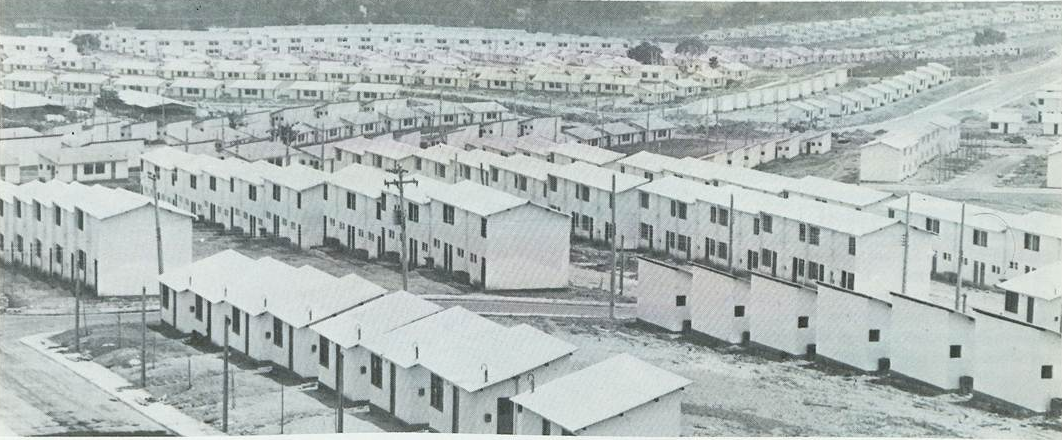

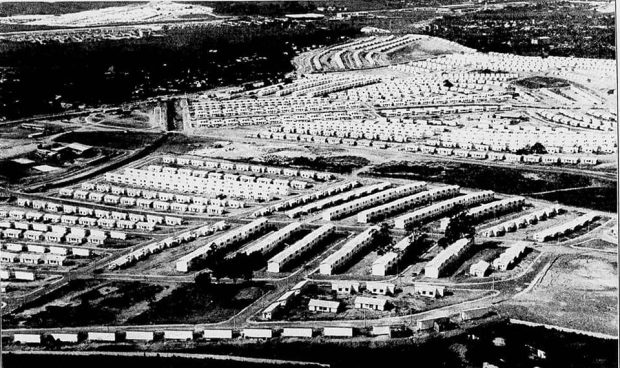

The Otacílio Camará Housing Complex, nicknamed “Cesarão”—alluding both to Cesário de Melo Avenue and to the housing complex’s enormous size (reflected in the suffix “ão”)—was the first residential complex built in Santa Cruz, a neighborhood in the extreme West Zone of Rio that, to this day, alludes to the promise of development. At the time, the public housing complex was the largest in South America.

Before becoming a housing complex, the land where Cesarão stands was a large orange plantation. However, by the time construction began, the area was already surrounded by the Aço, Rollas, and Antares favelas. Aço and Antares were the result of forced evictions in the 1960s and 1970s and were originally intended to be temporary settlements—that is, they were meant to provide temporary shelter for people from other favelas affected by heavy rains or eviction policies. Rollas, a large allotment, became the site of several violent territorial disputes between the former landowner and residents who occupied the land for shelter.

It was in this region that the construction of Cesarão was planned and carried out by the State Housing and Public Works Company (CEHAB). The houses were intended for low-income families earning between one and five minimum wages. Around 3,964 houses were built in three different sizes, designed to accommodate up to 20,000 people.

As reported in newspapers and in accounts by historian Guaraci Rosa, a considerable number of these houses were purchased by the Rio de Janeiro Telecommunications Company (Telerj), and some by the Rio de Janeiro Telephone Company (CETEL). The goal was to encourage employees from these state-owned utilities to become homeowners.

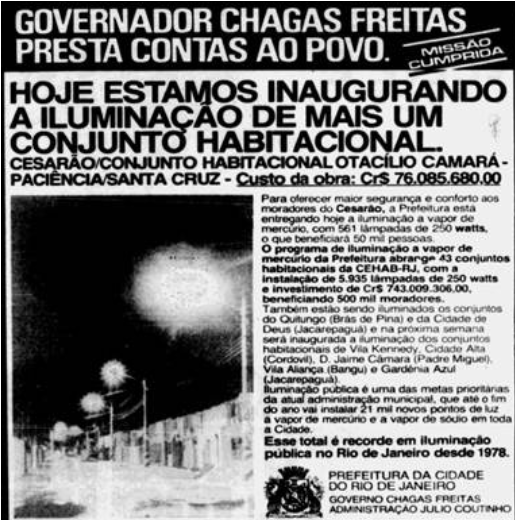

The utilities committed to building common areas, community centers, and leisure spaces—such as parks and playgrounds—in all of the established residential complexes, a promise that remains unfulfilled to this day.

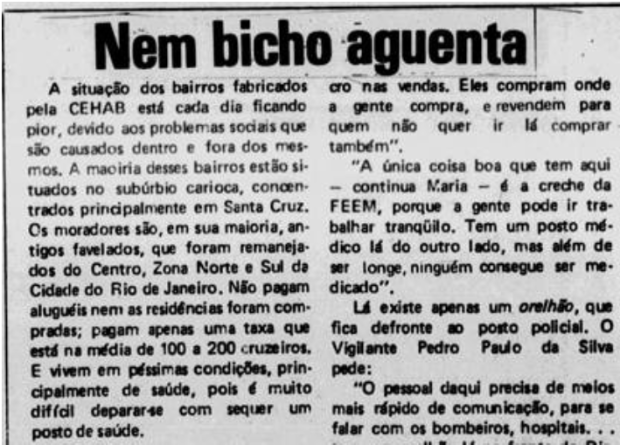

Other houses were allocated to families who had been forcibly evicted from different parts of the city and could afford to pay a minimal amount. As the first families began to arrive, what had initially seemed like a chance to rebuild their lives turned, for many, into a struggle and a source of frustration in the face of the reality imposed by the authorities at the time. The segregationist housing policy denied residents basic rights—including proper land demarcation, which was precariously carried out by the State and led to numerous conflicts among residents.

Black and socioeconomically vulnerable people were forcibly evicted and isolated from areas with greater access to the city, including education, leisure, and transportation. Upon arriving in Santa Cruz, the new residents encountered a lack of infrastructure and the absence of public policies essential to living with dignity. There was no public lighting, schools, security, or sanitation. Their new homes were often over two hours from their workplaces, and bus fare was expensive. As a result, many of those who had been relocated there chose not to remain in Cesarão.

Cesarão’s Controversial Fate: Abandoned Homes and Broken Promises

Many houses were never occupied by their intended owners. They were left behind, empty. Many families refused to move to Santa Cruz. Meanwhile, in the very precarious neighboring settlement, Favela do Aço, with its temporary structures, residents had already been waiting for 20 years for permanent housing promised by authorities following the floods of the 1960s that led them to the area.

However, the promise of better housing conditions was never fulfilled. Sixty years later, “temporary” homes in Favela do Aço still stand today. Temporary shelter became permanent housing, without proper care or attention from the authorities.

This dilemma raised a question: why weren’t the houses in Cesarão allocated to the residents of Favela do Aço? Many asked themselves this question as they found themselves hired to clean the very houses that would be given to residents from other favelas—who, in turn, felt as though they had been chosen to live at the “end of the world.”

Luciene Montes lived in Favela do Aço for 20 years and has been living in Cesarão for nearly 40. She says changes in government and political interests led to Favela do Aço being “forgotten.”

“It was [supposed to be] temporary. But then governments kept changing, and you know how it is—one administration’s ‘temporary’ is forgotten by the next. The new [mayor] comes along wanting to make a name for himself, not to continue the previous one’s project… The authorities at the time were interested in building for a different kind of person, not for the people from Favela do Aço. That way, the fellow in power could name the complex after himself and win votes, since he would have made it possible for those people to become homeowners. And Aço just kept being forgotten. That temporariness, which was never meant to last that long, is only now starting—or supposedly starting—to be addressed [since they’re currently, supposedly, building new housing for the residents].” — Luciene Montes

It is important to highlight that the promise of new housing during relocations and forced evictions is a political strategy that directly toys with the expectations of a population that is constantly under pressure by real estate speculation and incompatible rents. In many cases, this population needs to resort to precarious occupations in order to access the right to housing.

The history of Cesarão is just one among dozens of proposals that were never effectively implemented for the population. This longstanding State negligence regarding the right to housing affects the lives of millions. It is an aggressive model of urban development that ignores the social demands of favelas and peripheral areas, reinforces the exclusion of citizens, and violates the right to the city. The right to dignified housing goes beyond simply building houses—it involves providing and guaranteeing a social, political, and economic structure capable of promoting citizenship.

About the author: Moanan Couto is a resident of Cesarão in Rio de Janeiro’s extreme West Zone, and is currently pursuing a law degree at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ). She is a co-founder of the Levante Aço (Aço Rising) project and a project coordinator at the Besouro Institute. Her research focuses on the right to the city, to the favela, and Rio’s West Zone. Couto holds a deep affection for her city, its favelas and peripheral areas, and for public policies aimed at youth.