For the original in Portuguese with video, by Renan França, published in O Globo, click here.

The number is double what was estimated: the results are based on a database created by Emory University, in Atlanta.

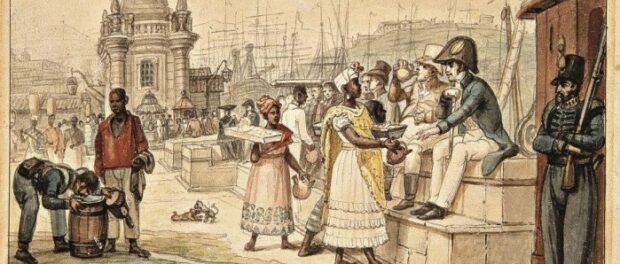

Between 1500 and 1856, one of every five enslaved people in the world was brought to Rio de Janeiro. It was the Port region, today the location around Venezuela and Barão de Tefé avenues, that received the bulk of slave ships coming from Africa, carrying even the bodies of those who couldn’t survive the voyage. For a long time it was imagined that few more than a million slaves disembarked in the city, while more than 2.6 million were taken to other parts of coastal Brazil. Now, studies confirm that the relative number in Rio is much higher than was previously estimated by various historians. This conclusion is based on a rigorous database created by researchers at Emory University, in Atlanta, USA: the archive compiles Port records going back three and a half centuries. The work is housed on the site slavevoyages.org and will be translated to Portuguese by the Casa de Rui Barbosa Foundation, located in Botafogo. According to the new information, close to two million slaves arrived in Rio.

“The previous calculation, adopted by various historians, was made by Maurício Goulart, who published ‘African Enslavement in Brazil’ in 1949. In his work, he confirmed that Brazil received 3.6 million slaves. The estimate that few more than a million arrived in Rio was based on records from the Cais do Valongo wharf between 1758 and 1831. However, there were other sites where slaves were unloaded off ships in the state, and we examined documents referring to the transportation of slaves in eight languages, dated to periods before and after those 73 years which, until this research, was the only period studied. Now, we have a more precise number,” says Manolo Florentino, the only Brazilian that participated in the project. In the Emory team’s research, 90% of the data for the Southeast region of Brazil applies to Rio, the main entrance port for the country’s slave ships.

In the study, 35,000 voyages were catalogued, documenting a flow of 10.7 million slaves worldwide. Researchers checked documents from various countries including the United States and England, in addition to Brazil and nations on the African continent. Many times, there were no records of the arrival of a slave ship in Rio, but its departure from another city was documented, for example, in Portugal. And, besides Cais do Valongo, Copacabana, Botafogo and other points in the city center served as disembarkment locations, albeit on a small scale.

According to the research, close to 4.8 million slaves arrived in coastal Brazil. Another number that demands attention, released for the first time, is the total number of lives lost in the trips between continents. According to research by the Emory team, close to 300,000 slaves died on their way to Rio.

“The research figures could be even bigger. We are preparing an update for the upcoming years,” says the historian and coordinator of the study, David Eltis.

Those interested can access the site or project and research the most intense periods of slave trafficking through historic clippings. In the first three centuries of Portuguese colonization, for example, Bahia received 15% more slaves than the South-Central region (at the time, the Southeast was included in this region). The situation changed after 1763, when Rio became the seat of the nation’s government.

The historian Marcus Dezimone, professor at the University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), explained that the climax of gold production in Minas Gerias, in the middle of the 18th century, turned Rio into a strategic place to receive slaves from Africa and send them to the mines.

“We had an idea that at that time Rio surpassed Bahia in the number of slaves received, but this research at the American university is important because it provided clarity on this period. Following the second half of the 18th century, the number of slaves who had recently arrived from Africa grew in Rio and stabilized in Bahia. No place in Brazil was functioning as much as an entrance for slaves as the city [of Rio].”

The countries that sent the most slaves to Rio were the Congo and Angola—in the eighteenth century, about 720,000 slaves arrived from these origins. After 1780, with the decline of mining activity in Brazil, a large number of slaves were taken to Vale do Paraiba, in the interior of the state where, much later, the expansion of coffee agriculture began.

The research also provided important insight about slavery in the 19th century: Rio imported more slaves than Cuba for work on coffee farms. Between 1831 and 1840, the researchers found that some 239,000 slaves were brought to Rio, compared to 186,000 to Cuba. The writer and researcher Tamis Parron, author of “The politics of slavery in the Empire of Brazil,” commends the research work and emphasizes that, previously, the flow of the slave trade had only been considered from a geography perspective.

“The analysis always favored Rio because of the position of the city in relation to the African continent. It was cheaper for the slave trafficker to arrive in Rio’s port than to go to Cuba,” says Parron.

Law for the English to See

Another period that lacked detailed information about the arrival of slaves to Rio was the period beginning in 1831—the year of the Law Feijó, which prohibited slave traffic in Brazil. The research site shows that, at first, the passage of the law showed results. In 1831, 900 slaves arrived in the city, compared to 31,000 a year prior. However, after 1832, human trafficking returned to high volume. The ineffective law coupled with pressure from the British for the end of human exploitation generated the expression, “para inglês ver,” or “for the English to see.” Between 1835 and 1850, approximately 564,000 slaves arrived in Rio illegally, according to Emory University.

As Rio gains this important database for better understanding its past, the city expects to see the Cais do Valongo wharf classified as a World Heritage Site. Anthropologist Milton Guran coordinates an academic team that will send UNESCO a file for candidacy in September.

“This 450th year since the foundation of Rio makes us reconcile with our roots. Rio was born indigenous and got a Portuguese baptism, but its ethnic base is composed of black roots, which was fundamental to our cultural formation,” he said.