- [ February 13, 2026 ] Queens from the Favelas: Meet Homegrown Rhythm Section Queens Upholding Black, Peripheral and Female Leadership in Rio’s Carnival by Community Contributors

- [ February 11, 2026 ] In Serrinha Favela, Kids Make Things Happen! Community Project ‘Mulecada Que Agita’ Continues the Legacy of Generations of Sambistas and Jongueiros [INTERVIEW] *Highlight

- [ February 9, 2026 ] Solidarity Kitchen and Social Impact School ‘Sweet Memories by Claudia Queiroga’ Feeds Body and Soul in Greater Rio [PROFILE] *Highlight

- [ January 29, 2026 ] ‘It’s the Place of Resistance of Our Existence’: Duque de Caxias’ Culture Manor is a Hub for Art, Education and Leisure by Community Contributors

- [ January 13, 2026 ] 10 Years Since the Rio Olympics: Vila Autódromo Continues to Resist Gentrification Pressures Amidst New ‘Olympic Barra’ Neighborhood #EvictionsWatch

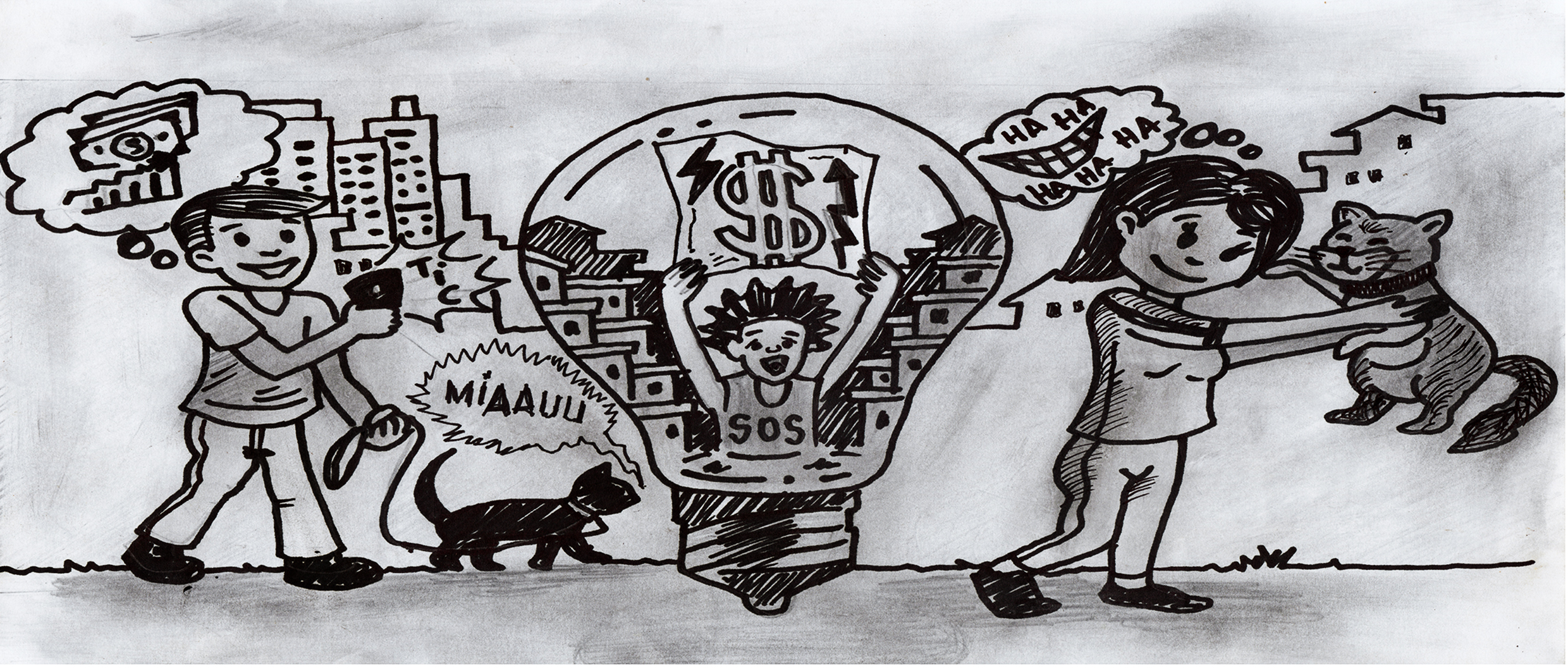

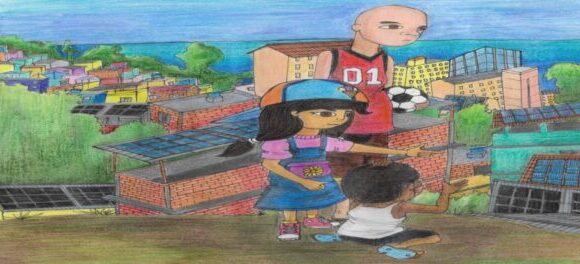

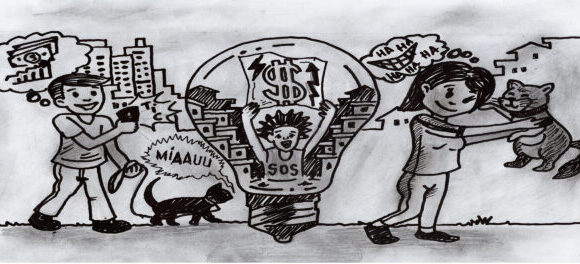

The series “Energy Justice and Efficiency in Rio de Janeiro’s Favelas” produced 18 articles, including original research, all carried out and illustrated by favela residents. The series aims to raise awareness of the topic by residents and opinion leaders, inside and outside favelas, inspiring better energy decisions while also informing movements to guarantee energy justice.

In introducing the series, RioOnWatch published an article that summarizes an international study where four researchers classified three distinct notions of energy justice: distributional, recognition and procedural justice.

Background

At the time of Rio’s urbanization, charcoal was the main energy source, essential for civil construction. Afro-Brazilians cleared the forest and transferred its energy to Rio’s center with their charcoal-making technology. Fragments of small kilns have been found in several parts of the Pedra Branca Massif, which played a crucial role in the construction of the city’s downtown.

In 2001, a brutal energy crisis brought on blackouts and a rigorous rationing of energy across Brazil. Energy cuts were even more common in favelas and added to pre-existing social issues, exacerbating inequalities in the access to basic rights, while generating financial losses.

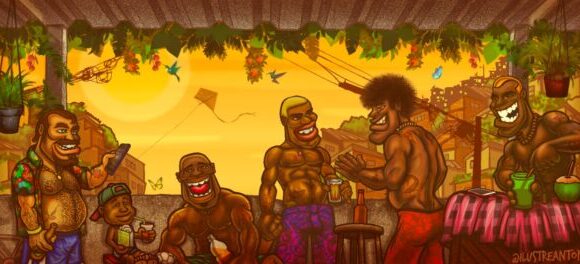

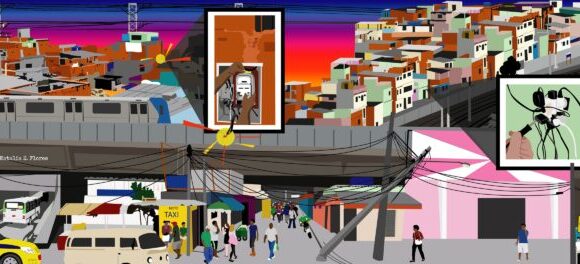

Given the universal need for energy and the local utility’s lack of provisions, “gatos”—as clandestine electrical connections are known in Brazil—emerged as a form of access to electricity in favelas. It is, nevertheless, an exclusionary form of access, not only due to the criminalization of these people and territories, but also generating safety risks.

Inequality and Energy Insecurity

Access to electricity is not recognized as a social right in the Brazilian Constitution. For this reason, cases of negligence in the energy sector are not considered a rights violation. Months ago, residents of Rio de Janeiro’s largest favela, Rocinha, created a WhatsApp group to denounce power outages.

The invisibility of the poorest results in countless families in the dark, in the heat, without refrigerated foods and cold water. Blackouts happen often in favelas and mean more difficulties in the daily routines of those who already live through fear, hunger, and lack of assistance. The service’s precariousness highlights inequalities and exposes families to unsafe electrical connections.

The Favela Data and Narratives Laboratory surveyed residents of the Jacarezinho favela regarding their perceptions of electricity services. The results brought, in figures, a well-known scenario to those who live there: half claimed to suffer blackouts at least once a week, and 75% said they have lived over a week without electricity.

Favelas pay a high price and get little benefit from their electricity providers, exactly the opposite of what society, in general, thinks of electricity in favelas. During the pandemic, the impact of this cost has been weighing even more on poor families. In the Palmeira favela, the lack of maintenance of the power grid is evident, and improvized solutions have come from residents themselves.

The service provided by the local electric utility in the Nova Divinéia favela is very different from the one supplied in the neighboring district of Grajaú. This inequality is evident in key points, such as chronic power outages during peak hours and how often they occur, electric bills that don’t reach residents’ homes, not to mention the company’s improper reading of electric meters and faulty maintenance of the grid.

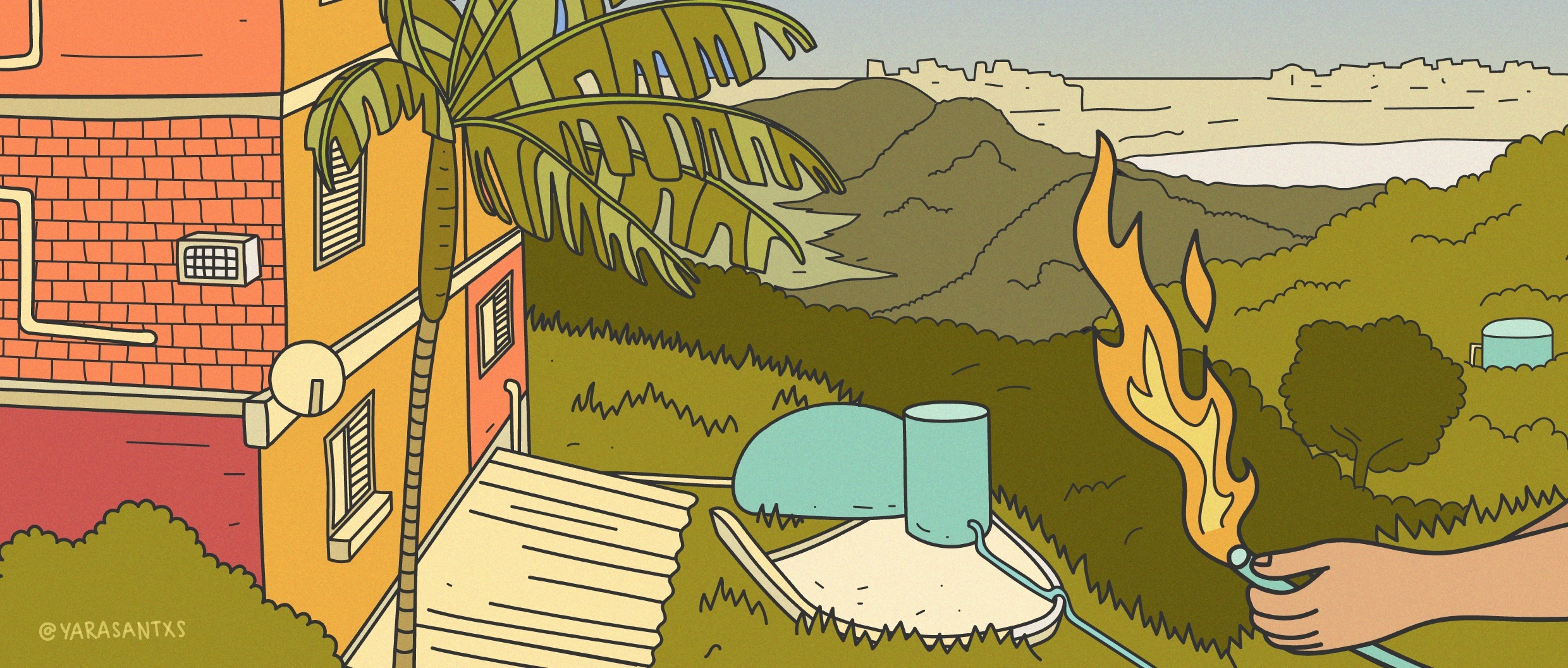

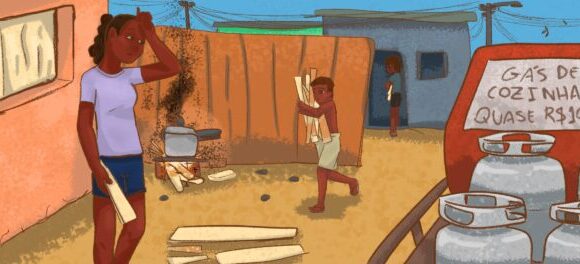

The rising cost of cooking gas has made the lives of poorer families even harder during the pandemic. Many are having to improvise with alternatives such as firewood and kerosene, both very risky. In this scenario, civil society organizations have mobilized to guarantee donations and discounts for the purchase of gas cylinders.

The César Maia favela, located in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, experiences a similar problem to many favelas in Rio de Janeiro: blackouts. The community has a Family Clinic whose services are constantly being affected by power cuts. Family Clinics are Covid-19 vaccination units. Amid this energy neglect, will favelas be able to store Covid-19 vaccines?

The electricity service provided in the Morro do Sereno favela in Complexo da Penha, North Zone of Rio, is deficient and expensive compared to the average income of residents. Research revealed chronic problems in the power grid that serves the community, culminating in everyday losses for those who live there. Furthermore, the lack of efficient public lighting causes a feeling of insecurity.

What is the perception of favela residents about the quality of energy service delivered to their communities? This issue guided a survey of 400 residents living among the 16 communities that make up the Maré favela complex, in Rio’s North Zone. A majority stated that they feel insecure with the electrical installations and more than half said they knew of a fire caused by problems in the power grid.

Energy Efficiency and Solutions

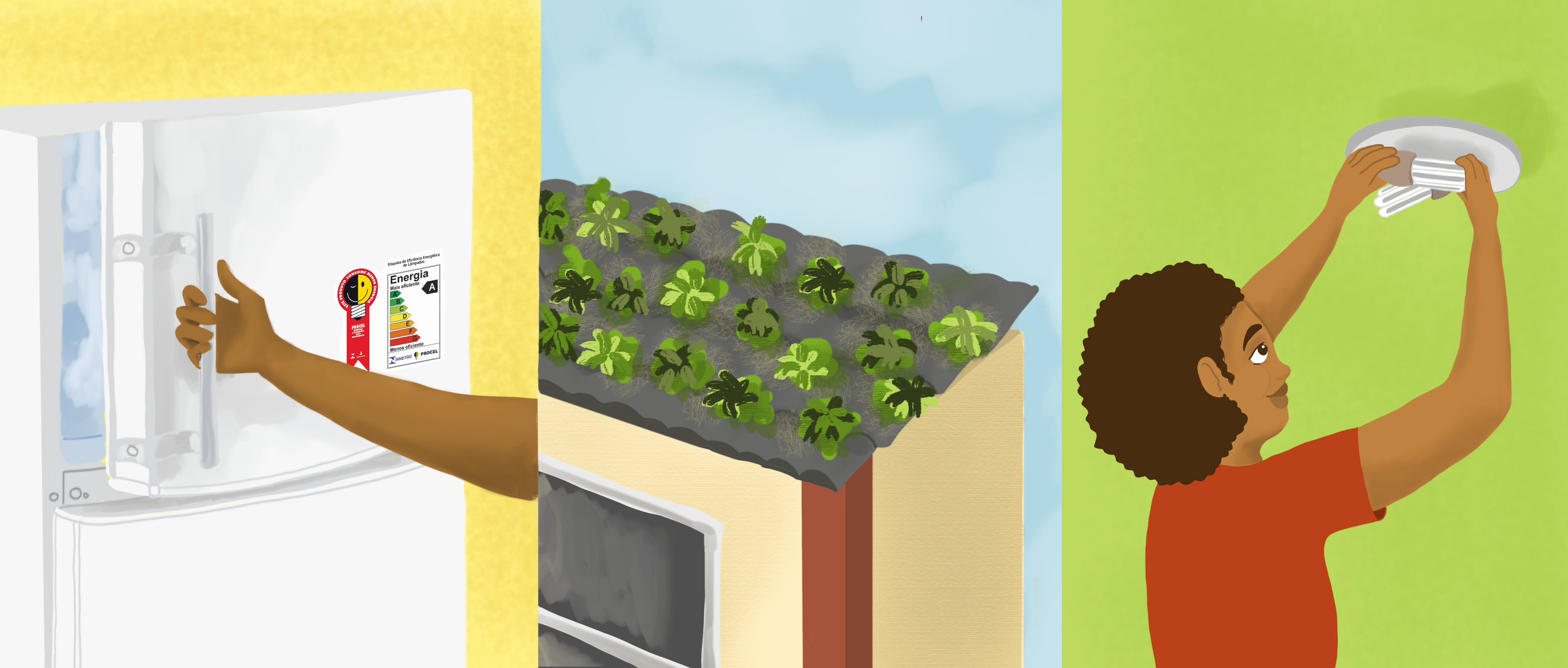

Have you heard of energy efficiency? This was one of the main questions asked to the residents of Conjunto Esperança that is part of the Maré favela complex. A community architect analyzes the efficiency of 16 homes, comparing public and self-built units. Her intention is to understand how much people know about energy efficiency, and to explain how to apply it in their daily lives.

The lack of basic sanitation is an old problem in Vale Encantado, a long-established community surrounded by the forest in Alto da Boa Vista. Residents’ search for a solution culminated in the construction of two biodigesters in the community. The first operates solely on food waste and produces biogas for Vale’s cooperative kitchen. The second treats the community’s sewage, producing biogas for local families.

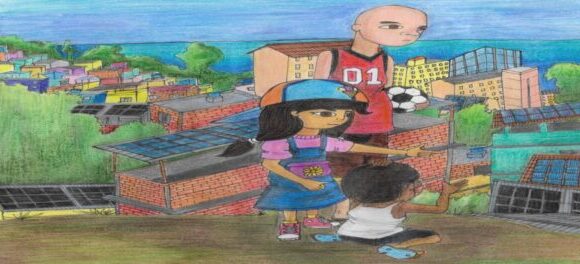

The production and consumption of solar energy is a reality in Rio’s favelas. Installations in the South Zone communities of Babilônia, Chapéu Mangueira and Santa Marta, most of them in community organizations and small businesses, have changed the scenery and electric bills. Besides being a clean and renewable energy source, the photovoltaic installations have created jobs and generated income.

The absence of vegetation, architectural limitations and other factors make it seem like the only solution to tame summer heat in Rio favelas is the use of air conditioning. Green roofs prove a better solution is possible, using plants to reduce the temperature inside homes. In Parque Arará, Green Roof Favela has proven that green roofs can reduce indoor temperatures by as much as 15° Celsius.

Awareness-raising and capacity-building activities took place in the São Gonçalo neighborhood of Jardim Catarina—the largest informal subdivision in Latin America—with the aim of reducing energy consumption and waste in the community. These activities, which included workshops and educational campaigns, are the product of partnerships between community organizations and the local energy utility.

The collection and correct disposal of waste has been part of a problematic reality faced by favelas. Generally regarded solely as a problem, garbage can also be seen as a possibility for generating income for favelas, as well as a way to improve socio-environmental, energy, and basic sanitation in these territories. Brazil already has waste-to-energy projects in operation.