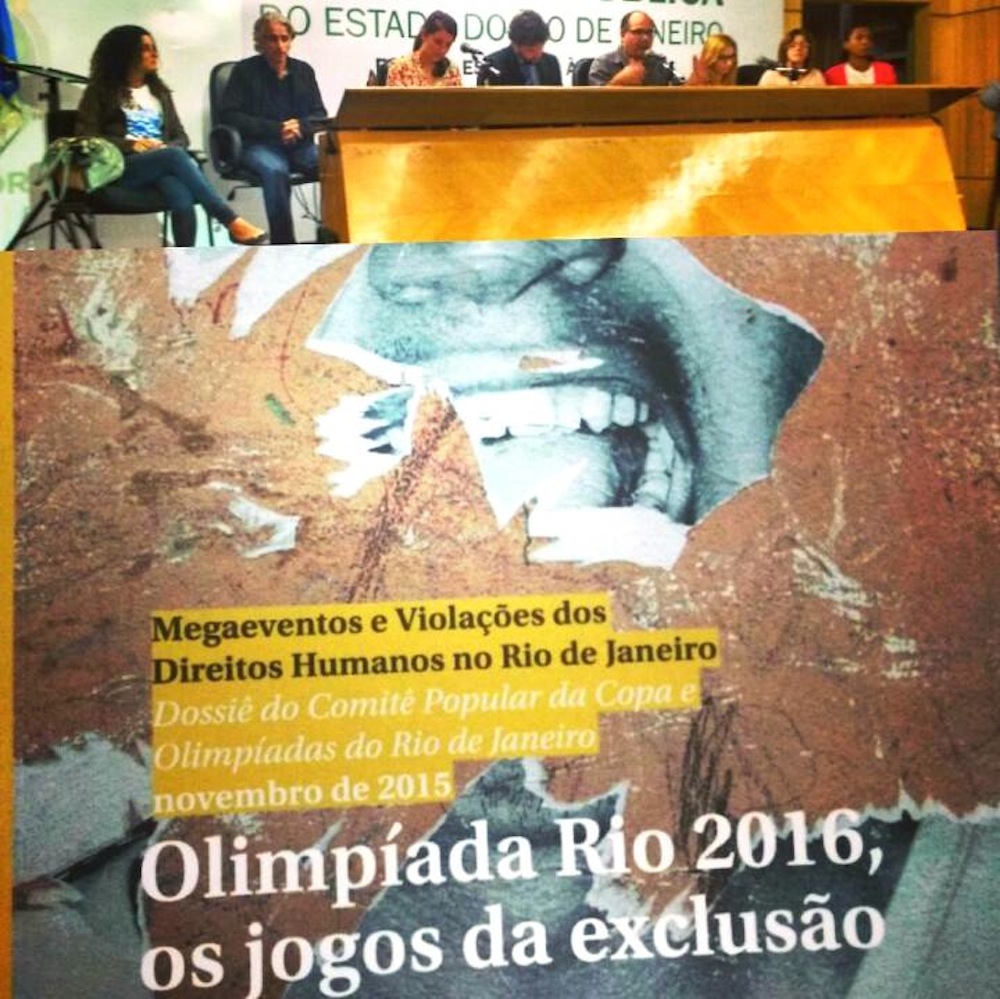

“The only reason it’s not a best-seller is because it’s not for sale.” A day in advance of the official launch on Tuesday, December 8, the Facebook page of Rio de Janeiro’s Popular Committee on the World Cup and Olympics proudly posted an image of its meticulously researched 190-page dossier on mega-events and human rights violations in Rio. The fourth edition in the series and the first Rio dossier since the 2014 World Cup, the November 2015 publication departs from past versions with an intensified focus on the 2016 Olympics. It’s the first dossier with a unique title—“Rio 2016 Olympics: The Exclusion Games”—and the first to be published in both Portuguese and English.

From the Dossier: “A total of 22,059 families have been removed in the city of Rio de Janeiro, amounting to 77,206 people, between 2009 and 2015, according to data presented by Rio de Janeiro’s City Hall in July 2015.” Rio’s Popular Committee estimates “at least 4,120 families have been removed and 2,486 remain under threat of removal, by reasons directly or indirectly related to the Olympic Project.”

The powerful panel at the launch event

The Popular Committee launched the dossier on Tuesday evening with a panel presentation at the State Public Defender’s office (Defensoria Pública do Estado do Rio de Janeiro). Some 100 audience members heard from eight speakers, including Marcelo Edmundo from the Center for Popular Movements (Central de Movimentos Populares, or CMP), who facilitated the event.

Popular Committee member and Metropolis Observatory researcher Mariana Werneck took the mic first with a brief overview of the new dossier. The “Exclusion Games” title, she explained, is a direct response to an article by Mayor Eduardo Paes which labeled the event as the “Inclusion Games,” following a similarly positive speech from IOC president Thomas Bach. Highlighting the various rights violations documented in the dossier, she summed up: “When we put all this together, we see what kind of city is being built:” one with “privatization…militarization…and the deaths of, principally, poor black youth.”

From the Dossier: Updated budget figures, released by the Olympic Public Authority (APO) on August 21, 2015, suggest that the private sector is paying about 57% of the Olympics and Olympic legacy budget. The Popular Committee argues the government excludes several relevant public expenditures, and that the private sector is actually paying less than 38% of relevant costs.

Next to speak was deputy head public defender Rodrigo Baptista Pacheco, who admitted the government “needs to regain the legitimacy we have lost over the past years.” He highlighted issues in which the public defender’s office must fight against exclusive policies, such as the prejudiced detainment of youth traveling from the North Zone on buses to South Zone beaches, and the debate on lowering the age of criminal responsibility.

From the Dossier: The TransOlímpica BRT still threatens over 1,300 people in three communities. “It seems that the implementation of the two [finished] BRT systems (Transoeste and Transcarioca) and the BRS has had no effect on reducing the number of private cars on the streets, the main cause of traffic jams.”

Up next was Edneida Freire, an athletics coach at the Célio de Barros Stadium, the public athletics center in the Maracanã complex that was closed without warning or full explanation in 2013. The Célio de Barros stadium ran extensive activities for children, many of whom couldn’t afford other activities, so it was a place where “we transformed lives.” She stressed the irony that “sports are suffering from this Olympic City,” asking “What legacy is this?”

Ana Paula Oliveira recounted how her son Jonatha was killed by Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) police in Manguinhos in 2014, emphasizing that his death was not a one-off incident, but a reoccurring result of a “lying, failed, and racist project.” She said: “It’s important to say that: ‘racist.’ Yes, racist. Because who dies? Our children, black children. It is unacceptable.” She explained that when the police kill a child, “they don’t just take our children, they take a piece of us too…It’s a necessity for me to speak about my son, because I’m not just talking about me, but talking about many children. I see there are many mothers who can’t do this.” She concluded with a powerful phrase that has been repeated in protests against the World Cup and Olympics: “The party in the stadium does not justify the tears in the favela.”

From the Dossier: The number of cases in which police killed “in self-defense,” increased between 2012 and 2013 “from 381 to 416 in the state of Rio de Janeiro, increasing again to 584 in 2014, and reaching 349 deaths just in the first half of 2015.” The September 2015 death of Eduardo Felipe Santos Victor and so many others now documented demonstrate that many of these “self-defense” cases are falsely justified.

Camila Marques from the NGO Article 19, spoke next, providing context for the contentious law currently under debate to define terrorism, a law activists worry will criminalize protesters. Revisions to the law’s language rule out the law being used against social movements, but Marques warned that it still leaves problematic space for judges to label a given protest act as terrorism, rather than social movement activity.

Resident of Vila Autódromo for twenty-three years, Sandra Maria began with the assertion that “what is happening in Vila Autódromo is not a result of the Olympics.” Instead, she argued, the historic “formation of the Brazilian people was already an unjust formation,” from colonization through slavery to the government’s abandonment of favelas. “The city is planned for the rich,” she said, while “the poor, who built this city, don’t have the right to it.” In Vila Autódromo’s case, land titles were given “when nobody wanted to live there,” but later the growth of neighboring Barra da Tijuca made the site valuable. “If only [the problem] were just the Olympics,” Sandra stated, “it would be much easier!” She believes that after the Olympics there will simply be new justifications for the elitization of the city.

From the Dossier: Rio’s Public Labor Ministry identified “conditions analogous to slave labor at the construction company Brasil Global Serviços, responsible for the development at the residential complex Ilha Pura, where the Olympic Village will be located and which will lodge athletes and organizers during the 2016 Olympic Games.”

The last panelist to speak was Jules Boykoff, a political science professor from Pacific University who drew parallels between transformations in Rio and the rising costs, militarization, and removals and gentrification that occurred ahead of the London 2012 and Vancouver 2010 Olympics. The legacies promised by mega-event hosts, he concluded, are “beautiful, big and ambitious. The only problem is that they’re not true.”

From the dossier: After admitting the Olympic bid promise to reduce Guanabara Bay pollution by 80% is impossible by the Olympics, “City Hall is working now towards a 40% de-pollution goal.”

The dossier’s intensified Olympic focus

Much of this latest document reflects the structure and evidence of previous Rio dossiers, from March 2012, May 2013, and June 2014, as well as the September 2015 dossier on violations to the right to sport. However, the dossier’s introduction highlights four new Olympics-focused take-aways:

- Removals connected to the Olympics continue to affect or threaten thousands of families, contrary to official government discourse.

- Instead of the promised sporting legacy to benefit the whole city, public sports spaces have been privatized.

- The growing militarization of the city and racist public security policies predominately affect young black men in favelas, but generally enhance segregation and the criminalization of social movements.

- Although the City claims public expenses are smaller than private expenses, “the Olympics represents the transfer of public resources to the private sector, subordinating public interests to market logic.”

In addition to updates to statistics and ongoing cases, some of which are featured throughout this article, the Popular Committee also revised and expanded its proposals “for a city for everyone, with social justice and democracy.” In summary, these sixteen recommendations call for:

- An end to forced removals

- An end to harassment of street vendors

- The re-opening of the Célio de Barros Athletics Stadium and the Júlio Delamare Water Park

- A return to the popular use of the Maracanã stadium

- The regrowth of APA de Marapendi

- The right to protest without criminalization and the release of political prisoners

- An end to militarization, favela occupation, extermination of the black population, and police violence

- Sports as education, health, leisure, not as business

- The provision of popular housing and facilities on all surplus land from public developments

- An end to the privatization and gentrification of the Lagoa Rowing Stadium and the Glória Docks

- The replacement of the Public-Private Partnerships with popular projects for the Marvelous Port and Olympic Park

- The cleaning of Guanabara Bay and Rodrigo de Freitas and Jacarepaguá lagoons

- Adequate public transportation free of charge for all

- The reinstatement of teachers and street cleaners fired for protesting

- An end to the forced removal of street children from the streets, and

- An end to the “World Cup Law,” which allows FIFA, the IOC, and sponsors to profit without paying taxes, and without concern for social justice and democratic participation.

These proposals reinforce the Popular Committee’s message that the dossiers should not serve only as documentation of violations, but also as invitations to join a movement for an Olympics, and cities, for the people.