Reporting by: Glenda Fernandes, Saulo Araújo, Hosana Souza, Josilaine Costa, Samuel Lima, Henrique Ribeiro and Amanda Souza.

One of the healthiest aspects of Brazil’s young democracy is its widespread religious freedom, which means most of us are at a loss to understand the bloody religious wars happening elsewhere in the world. But those who live in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro know that one of the achievements of the new State community policing (UPP) presence in some favelas is the ability to worship without the risk of having one’s house broken into by drug traffickers, as happened many times in Morro da Formiga, a recently pacified favela in the North Zone of Rio. Since Comando Vermelho, one of Rio’s four main organized crime factions, took control of drug sales in the community, spaces devoted to the worship of Umbanda and Candomblé (religions of Afro-Brazilian descent) had been banned. There were several deaths in the community, including that of the president of the Neighborhood Association. His daughter to this day feels unsafe to speak openly of her father’s death, and so has asked he not be identified.

One of the most rumored cases of religious intolerance in low-income communities dominated by the drug trade occurs in Favela do Dendê (on Ilha do Governador), whose drug boss ended up on the pages of the sophisticated New Yorker magazine after converting to a neo-Pentecostal sect and banishing Umbanda and Candomblé worship from the community. The traficante from Ilha do Governador is a loyal follower of one of the many Evangelical churches in Rio, and is associated with Terceiro Comando Puro, the same faction to which Alberico de Azevedo Medeiros, also known as Derico, belongs. Derico leads the drug trade in Favela do Acari, and his conversion to the Assembly of God of the Last Days Church was so spectacular that it was thought he had given up crime while a prisoner at Laertius Costa Pellegrino, the maximum security prison more commonly known as Bangu 1. Although there has been no news that Derico has outlawed Afro-Brazilian religions in the favela he has controlled for almost 15 years, sociologist Chris Vidal’s master’s thesis, entitled Evangelical Occupation and defended at the Institute of Philosophy and Social Sciences, shows the growth at an almost omnipresent level of neo-Pentecostal sects in the absence of police presence in the middle of the 1990s.

According to residents of Formiga, drug traffickers with the Comando Vermelho mainly began to persecute followers of Candomblé after a woman, disgusted by the disappearance of a community leader, put a curse on those responsible for the death so that they would suffer a similar fate, whether in conflict with the police or in one of the constant wars between factions in the community. “And they died,” celebrates the daughter of the community leader. There remains a theory that the Comando Vermelho traffickers could have been avoiding typical betrayals involved in drug trafficking by expelling from the favela those connected to the deposed leader after a battle. It’s known that Claudinho, the deposed leader of Formiga associated with Terceiro Comando Puro, was a follower of Candomblé. However the fact remains that the few Umbanda and Candomblé followers that remained kept their worship hidden, even avoiding lighting candles and especially avoiding beating the tambourine at night festivals in homage of the orixás (Afro-Brazilian religious deities). These were the people that could return to Formiga once peace was restored.

Not long after pacification, Cíntia Luna, president of the Neighborhood Association of Fogueteiro, in Santa Teresa, in the central region of the city, saw some changes regarding religious freedom as a result of pacification in this community where she was born 33 years ago. “The chapel was clean again,” she tells us. The chapel is a small religious temple at the entrance of the community, in which one can see the images of Saint Cosme and Saint Damian, two Catholic saints that, like Saint Jorge, are worshipped in Umbanda and Candomblé. “After a long period of abandonment, today these images are replete with offerings, like sweets, sodas, and toys,” says the community leader. The traffickers of Fogueteiro had such a strong alliance with the local Catholic church that they even paid for the Priest to have weekly mass in the Saint José Operário church, at which attendance was mandatory. The emptying of the chapel at the entrance of the community was the last step in the process that started with the removal of images of orixás like Maria Padilha and Exu Caveira, found at most intersections in the community back when Afro-Brazilian religions were predominant not only here, but throughout the low-income areas of Rio de Janeiro. “The new generations of drug traffickers thought the orixás were evil, even though they, themselves, were perverse,” says the community leader.

Trident of the ADA

Intolerance is not a mark of all communities dominated by drug trafficking or even by militias, the newest form of organized crime in Rio de Janeiro. This is what was gathered by our reporting team in low-income communities like Cesarão, Vila Vintém, Cantagalo, Vila Aliança, São Gonçalo, Morro do Fogueteiro and Comendador Soares, in Nova Iguaçu. As in other low-income areas of the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region, both the Catholic Church and Afro-Brazilian religious followers lost ground to diverse Evangelical sects. But it is no wonder that the symbol of the ADA (Amigos dos Amigos, or Friends of Friends) criminal faction that controls Vila Vintém is a trident. The trident is the symbol of orixá Exu Caveira, of whom Celso Luís Rodrigues, Celsinho of Vila Vintém, is a follower, as was Ernaldo Pinto Medeiros, also known as Uê, and José Carlos dos Reis Encina, also known as Escadinha, both killed in Rio de Janeiro’s drug trafficking war. Founders of the faction at the turn of the century, they marked their territory with the trident. Perhaps following in the generous tradition of Afro-descendent religions, the drug traffickers of ADA did not persecute pastors or priests that worked in their communities.

Though it may be an exaggeration to claim that all drug traffickers associated with the Amigos dos Amigos faction worship Afro-descendent orixás, Serrinha, in Madureira, is another example showing that drug traffickers not only tolerate, but are also followers of saints revered by Candomblé. This is the case of the drug trafficking chief of Serrinha. His passion for Saint George is so great that the trafficker sponsors the feijoada (a traditional Brazilian stew of beans with beef and pork) served after the Império Serrano samba school parade on April 23rd, known as the Day of the Warrior Saint, kicking off the party that goes until the early morning with a lot of pagode and funk (genres of music in Brazil). The drug traffic leader’s passion for the saint associated with the Orixá Ogum may derive from the fact that he was born on the day that Rio de Janeiro stops to revere Saint George, but this is not the case for the accomplices that join him in rituals in the chapel that he ordered be built. “Almost all of the traffickers here are followers of the Warrior Saint,” says the drug trafficker, who identifies with Saint George for never having lost a battle. Serrinha is one of the last favela communities of Rio de Janeiro where the so-called espíritas (Afro-Brazilian religious followers) are still a majority.

There is still no record of religious persecution in territory dominated by the militias, though it is known that some of its leaders also follow the Evangelical wave. This is the case of Cesarão, in Santa Cruz, in the city’s West Zone, that, according to the Evangelical Marinaldo dos Santos Junior, “is almost too ecumenical as a community.” The manicurist Ana Maria Paes, follower of Umbanda, confirms the Evangelical’s story, saying that in the 27 years she has lived in the biggest housing project of Latin America, with its 7,000 homes, she has never suffered any kind of religious constraints.

Shop keeper Maria das Graças Sales, 23, has faced unpleasant situations in the Ouro Preto housing project, in Nova Iguaçu, North of Rio but within the Metropolitan Region. But she says it would be unfair to attribute the conflicts with neighbors to Juracy Alves Prudêncio, also known as Jura, the Military Police Sergeant that controls the local militia even though he has been in jail for two years. “My biggest problem is with the neighbors,” she says, who are “very stubborn and talk a lot of nonsense.” It is worth remembering that the housing project has been associated with the Evangelical church since its founding and that Catholics were the ones who had the most problems getting along in close proximity.

6,000 churches

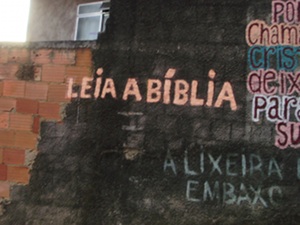

São Gonçalo, another municipality in the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region, according to a study conducted by a group of regional pastors, is the city with the most churches per square kilometer in Latin America. There are hundreds of different denominations spread out among 91 neighborhoods in the municipality. “The estimate is that approximately 6,000 Protestant churches are distributed in the entire city,” claims a member of the First Baptist Church of Brasilândia, who asked not to be identified. One of these churches is the Ministério Resgatando Almas (Saving Souls Ministry), in Complexo do Salgueiro, whose pastor, Luiz Cláudio, was involved with the omnipresent drug trafficking of his community until turning his life over to God, about seven years ago. Now, at 29 years old, Pastor Luiz Cláudio reports to have already converted murderers, assailants, addicts, and drug traffickers, in addition to having stopped extrajudicial drug trafficking executions. “My work is based on the saving of people involved in crime and drugs in the community,” he says. For the pastor, bravery is not carrying a pistol or rifle, but “holding a bible and joining the battle of rescuing lives and souls.”

Community leader Cíntia Luna has witnessed several negotiations between Evangelical pastors and drug traffickers that have prevented the death of individuals condemned by the merciless courts of the “parallel power.” “Once the pastor called me when he went to defend a boy accused of being a police informant,” says the Neighborhood Association President of Fogueteiro, who knows that this is such a serious accusation that the majority of the time, the accused is killed with a shot in the face, so that loved ones will not be able to kiss them goodbye. “He said to the chief of the traffic in Fogueteiro ‘man, if he is being judged for something, then he also deserves a defense, and I’m here to advocate for him.’ The traffickers kind of continued answering back, though with less force.” After a lot of conversation, the boy was banished from the community. He only returned at the beginning of this year, after police established the UPP of Santa Teresa.