As the world’s biggest sporting mega-events draw closer, Brazilian authorities will be expected to ensure borders, ports of entry, and territory are secure from threats and clandestine activity. However, security blunders during the Pope’s visit, ongoing conflicts between police and demonstrators, and public threats from organized crime groups promising a ‘World Cup of terror’ pull Brazil’s suitability to host international events into question.

Deconstructing Security

While security threats to international visitors are worrisome, fundamental concerns about the social fabric of Brazil are masked by these worries, with longer term concerns at the core. One of the main problems facing Brazilian citizens is the everyday use of violence in epidemic proportions. UNODC data reports a steady 22 intentional homicides per 100,000 since 2005. Intentional homicide data varies between states, with northern states such as Maranhão reporting nine times as many (297 per 100,000) as Rio de Janeiro (34 per 100,000).

Many are frustrated with a vanishing social contract and decreasing credibility of state institutions. One reason is due to the small amount of headway made by the state in significantly reducing crime and violence. Another is because security forces entrusted with keeping order and guaranteeing the rule of law on behalf of the state are frequently implicated in abusive, violent, or criminal practices. A recent poll conducted by the FGV in São Paulo revealed that 70% of Brazil’s population does not trust police work.

Between 2001 and 2011 alone, 10,000 cases of ‘justifiable homicides’ (autos de resistência) were recorded by the Public Security Institute (ISP) in Rio de Janeiro alone, with most cases offering police impunity. In 2011, only 13 military police deaths were recorded by Rio’s Public Security Institute. That said, ISP data should be considered critically following changes to data collection methodology which now only counts deaths of officers during shift hours, and not during free time when most police deaths occur.

If or when cases of police abuse receive media attention, responses tend to apportion blame to individual police officers, rather than understand the action through mismanagement or institutional failure. Discourse around the Amarildo case, a Rocinha bricklayer whose disappearance in July after being taken for ‘questioning’ by UPP officers garnered huge local and international media attention, is testament to this.

This framework informs the policing strategy. Recently, Rio State Security Secretary, José Mariano Beltrame, reaffirmed the policy of placing young officers in Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) posts in order to promote policing “without the vices of war and corruption.”

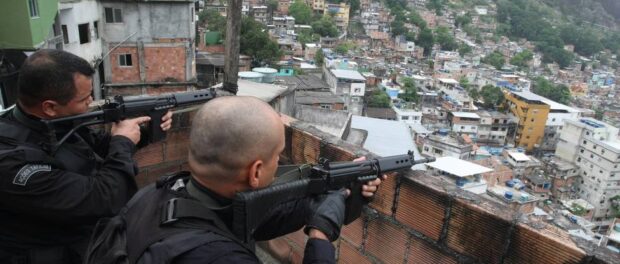

A similarly limited framework informs the current security strategy, which perceives criminal activity as a result of state failure. The state’s solution is to reinstate a stronger state presence, such as the ‘clear and hold’ strategy to (re)territorialize and homogenize favela spaces, carried out by the highly militarized Special Operations Battalion (BOPE) and UPP units.

Only by accurately identifying the problems can effective policing and security strategies be constructed. Without shifting the conceptual framework to reflect contemporary considerations it is likely that ‘bad habits’ from the past will be further embedded rather than avoided.

A Transition Hindered by Authoritarian Legacy

A brief historical analysis will help contextualize why police repression remains dominant and challenges the democratic project.

In the two years following the end of the military dictatorship, Brazil’s new 1988 Constitution was drafted by elected constituent committees. Although seemingly democratic, the underpinnings of the process were flawed as citizens were unaware when electing their constituents that would be involved in constitutional reform.

Democratic contradictions also made their way into the final constitution. Whilst many of the constitution’s 246 articles were progressive in advancing the democratic project by limiting the state’s ability to restrict freedom, the process was hindered by military elites. As a result militarized domestic security apparatuses have operated far beyond the end of the military’s term in office.

Ricardo Fiúza, then Minister for Social Action, played a key role in blocking demilitarization attempts. Fiúza argued the government would need as much force as it could muster in order to combat social resistance movements. He achieved the block by lobbying the subcommittee. Of the 28 who presented to the subcommittee, 25 were from existing military forces or pro-militarization.

Constitutional articles dealing with the armed forces, military police, and the military judicial system remained much as they had done in the 1967 Constitution. In fact, some articles were rewritten in even less democratic fashions.

Armed Forces Article 142 is concerning. According to political scientists Mathias and Guzzi, this article advances the civilian democratic project, while simultaneously consolidating guardianship of national values under the military: “The Armed Forces, constituted by the Navy, Army and Air Forces, are permanent and ordinary national institutions, organized by hierarchy and discipline, under the President’s supreme authority.” The emphasis, added by Mathias and Guzzi, highlights rewritten content in which the military appropriates permanence.

Public Security Article 144 is also problematic, with two concepts arising in Paragraphs 5 and 6 of Section IV. Firstly, it outlines the military police’s role as preserver of public order and actor of ‘ostensible (visible) policing’ on the streets. Secondly, the military police are ancillary services to the armed forces, suggesting an intrinsic tie to military structures and training models of the army which pursue indiscriminate but obedient agents.

Public Security Article 144 is also problematic, with two concepts arising in Paragraphs 5 and 6 of Section IV. Firstly, it outlines the military police’s role as preserver of public order and actor of ‘ostensible (visible) policing’ on the streets. Secondly, the military police are ancillary services to the armed forces, suggesting an intrinsic tie to military structures and training models of the army which pursue indiscriminate but obedient agents.

Other articles emphasize the military’s autonomy and impede the citizen democratic project more directly. Administrative detention frequently suggests a deprivation of liberty, as reported by the UNHRC earlier this year. Also, the 1983 National Security Law devised during the dictatorship to maintain order and control was invoked against political demonstrators in September 2013 in Rio and São Paulo.

The complex institutional status of an embedded military police in Brazilian domestic affairs highlights the dangerous ability of the military to block progress towards a full-fledged democracy.

Urbanization Incubates Insecurity

Following the end of developmental state policies, paralyzed by the country’s fiscal crisis in the 1980s, rural labor forces migrated to cities such as Rio in search of employment and opportunity. Housing and welfare services failed to serve migrants, and in Rio’s particular case with a stagnant economy from 1975 through 2005, the conditions were there for new arrivals to expand peripheral favela settlements in search of housing, with some veering into criminal activity as their means of production.

Rio’s police forces struggled to maintain control. Police forces continued a ‘public order’ policing approach (carried over from the dictatorship) with increasing levels of corruption and use of coercive force permitted. Barely existent levels of state-imposed discipline upon police forces allowed bribery to become institutionalized in policing practices.

This benefited both police and criminals: for criminals it was easier to offer a bribe than be convicted by the judiciary system, and for underpaid police officers it was in their personal interest to accept bribes rather than serve a vast and unstable justice system. A fertile space free from state control allowed deeper forms of criminal activity to germinate.

Effects from globalization were felt as transnational flows of capital, commodities, and international criminal networks allowed new forms of criminality. For example, the increased demand for cocaine in Europe played a part in the 10-fold increase in number of cocaine seizures between 2005-2009 in Brazil’s ports as transnational trafficking networks used busy shipping ports to export drugs to the west coast of Africa. Or, more recently, as global capital investment flows in Rio property markets triggered favela evictions, speculative markets, increased public spending on securitization of key investment areas, and insufficient public service spending.

As citizens continue to look for their own solutions to problems of insecurity, new non-state actors and organizations are emerging. Powerful militia groups, mercenaries and death squads, vigilantes, private police and security companies, seek political or economic security. By establishing a sense of security for themselves, these actors simultaneously contribute to the spiraling landscape of insecurity.

Conceptual Reform: Towards a 21st Century Social Contract

Brazilians are living in transitory times in between a militarized state apparatus, a vibrant civil society pushing for full democratization, and external forces of globalization. With many moving parts it is impossible to predict where the transition will lead, but it is likely citizens will continue to diversify their solutions to security as long as the modern Brazilian state weakens. If this is the case, the social contract between state-citizen will demand reformulation and non-state security solutions will also seek contractual responsibilities in society.

The future poses a vast security challenge for the modern Brazilian state. In order to retain legitimacy and control violence it must seek out creative ways to strengthen itself and consolidate new state-citizen relations. Self-critical institutional weaknesses should shape a serious debate around demilitarization of the police as one possible step towards this future. And although various constitutional amendments are in circulation advancing the demilitarization or unification of civil and military police (e.g. PEC 430/2009; PEC 102/2011; PEC 51/2013), it will be a long road to a police that defends the citizen over the state. Earlier this year the UNHRC called for demilitarization of the police showing promising signs of mounting multilateral encouragement.

Nick Pope is a Candidate for the Masters of Science in Globalisation and Development at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London where he is researching organized crime, urban space, and state relations in Latin America.