On Thursday afternoon, November 7, 100 residents and supporters of Vila Autódromo gathered in the rain to protest outside City Hall, a response to the City’s latest tactic to undermine their resistance to removal. The week prior, on October 30, it appeared city officials had orchestrated a protest of approximately 20 residents who want to leave their homes in Vila Autódromo for apartments in Parque Carioca, the designated resettlement housing complex. Participants recounted that city employees “mobilized” several families who are considering resettlement housing and transported them on buses to City Hall.

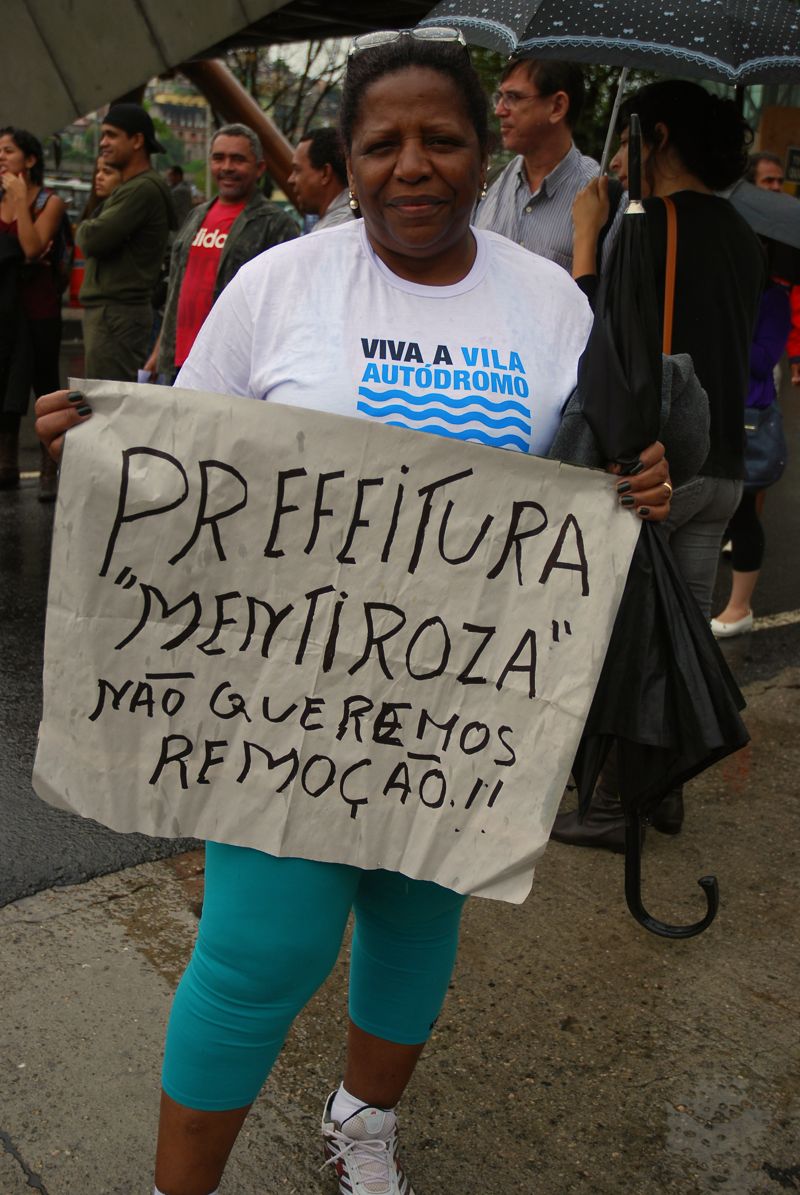

Longtime Vila Autódromo resident and activist Maria da Penha described the Thursday protest as “a response to the farce that the City staged.” She continued: “We are here to demonstrate that Vila Autódromo does not want to leave.” Community members marched around City Hall chanting, “The city government lies, we don’t want removals!” They carried banners illustrating the central demands of the resistance effort and identified the forged protest as further evidence of the mayor’s intention to remove Vila Autódromo in its entirety.

Thursday’s protest–in juxtaposition with the seemingly staged event a week prior–highlights a trend in the City’s position toward Vila Autódromo: the mayor publicly says he is negotiating the community’s permanence while in practice he is overlooking viable proposals that minimize removals; city officials are employing coercive tactics to convince residents to sign away their homes; police action creates a climate of fear and mistrust, which have inhibited protests both in and outside the community; and media giant Globo’s reporting gives huge attention to efforts to remove while ignoring or undermining resistance efforts.

Ongoing Resistance Efforts Include Updated People’s Plan

Vila Autódromo is a symbol of resistance to forced removal in Rio de Janeiro, having fought and won battles against eviction over 20 years. In recent years, the westward expansion exclusive shopping malls and luxury condominiums in Barra da Tijuca has left the community’s land extremely valuable for real estate developers. The community received a 99-year “concession of use” land title in 1994, but has been threatened with removal by a series of ever-shifting justifications related to the future Olympic Park. With the law on their side, residents have remained adamant and vocal in their demand to remain, and their case is still in the courts.

Alcides Faustino Gomes, an elderly resident of Vila Autódromo that participated in the protest against removals, stated, “I don’t want to leave because, however simple it may be, that is my house and my life,” playing on the title of Brazil’s federal housing program Minha Casa, Minha Vida. “You take cattle and move it to wherever you want, but not human beings. We have our own will, our owns desires and dreams.” He elaborated that the monthly utility and maintenance costs of the new Parque Carioca relocation housing will be impossible for families earning the minimum salary.

“Mayor Eduardo Paes ignored Vila Autódromo’s People’s Plan to sell the land to a consortium,” read one of the banners held by protesters on Thursday. This refers to the Public-Private Partnership that will facilitate the post-Games transfer of 75% of the Olympic site to private real estate developers. Protest organizers argued that a process of “social cleansing” is underway in Barra da Tijuca, in which the poor are removed from desirable land: “Why doesn’t the mayor make improvements and upgrade Vila Autódromo with basic sanitation?” Maria Melo, a long-time resident, asked.

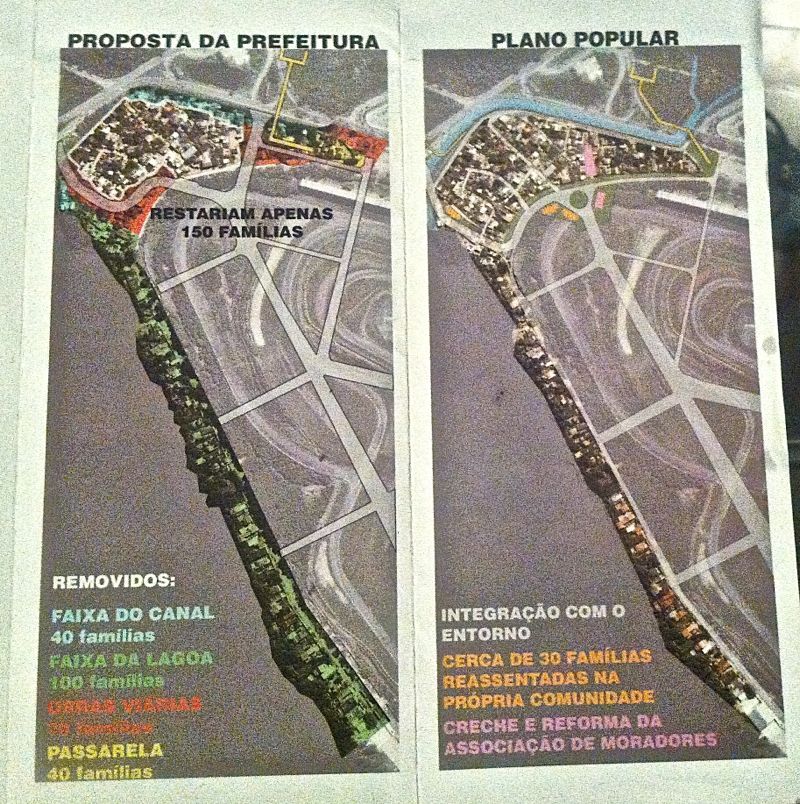

Insisting on removal, the mayor has consistently disregarded the People’s Plan for Vila Autódromo, a community-designed upgrading plan that has received international recognition. The proposal would allow for the permanence of Vila Autódromo at a significantly lower cost than relocation and in ways that do not infringe upon the Olympic project. Additionally, the People’s Plan minimizes the number of families removed and plans for their resettlement within the community.

Despite the August apology and announcement that the mayor would allow the community’s permanence, his most recent proposal would remove 278 families. This plan calls for several arbitrary and unnecessary roads that slice through the community to provide private elevated access for athletes and journalists onto the Olympic site. Urban planners suspect this design would force the remaining 150 residents to leave, due to ensuing water drainage problems.

In response, the team behind the People’s Plan–a partnership between residents and urban planners and architects from public universities–issued an updated design that met the requirements for the access roads and pedestrian bridge. The People’s Plan would only remove 30 families and allocates space for their resettlement within the community. A side-by-side comparison shows how easily the City’s plan can be redrawn to minimize the number of removals.

Showing consistent willingness to work within the demands laid out by the City, the design team of the People’s Plan has continuously designed alternatives that would remove fewer houses and upgrade the community in a dignified way. Residents and community advocates fear the tactic of partial removal for roads and other installations will inevitably result in the complete removal of Vila Autódromo. Examples in other communities have shown that demolished areas create unbearable conditions that force out those who remain.

Coercive City Tactics

In recent months, various coercive tactics have been employed in housing negotiations with Vila Autódromo. City officials, including the sub-mayor for Barra de Tijuca and Jacarepaguá, Tiago Mohamed, have been circulating on a daily basis in an attempt to convince residents to sign up for the Parque Carioca housing and making false promises about the size, costs, and regulations of the apartments they will be receiving. According to the latest release from the team working on the People’s Plan: “In order to convince them to leave their houses, the City is persuading residents to sign an agreement that does not give any guarantee to the families and obliges them to give up their rights. The document is worded in such a way that the resident who signs it ends up proposing the demolition of their own home.”

Maria Melo was considering accepting the Parque Carioca housing until she attended the meeting with the Mayor in RioCentro and observed that residents are being deceived: “Before, when I was considering negotiating and leaving, I thought things were being done in a legal and honest way, but they are not.” She went on, “When you arrive at the sub-mayor’s office, there is a lot of pressure. They tell you to sign the document to guarantee your apartment and if you say ‘I don’t know yet,’ or ‘I want to find out the value of my home first,’ they respond that you run the risk of losing the offer. They put a lot of pressure on you, so many people give up and accept the apartment.”

Community leaders also affirmed that many residents involved in last week’s “protest” were misled by city officials. “Residents reported that some were angry that they had been tricked. [They were told] they were going to a meeting with the mayor, and when they got on the bus they realized it was a demonstration,” Maria da Penha recounts. Additionally, rumors circulate that the mayor’s allies in the community receive various forms of compensation.

Disproportionate Police Force at Thursday’s protest

Recent developments in Vila Autódromo evidence a broader pattern of urban governance that values elite interests over the rights of citizens, including the right to protest and to a free press that is not bound to any center of power.

Jane Nascimento, director of Vila Autódromo’s neighborhood association, spoke of the inconsistencies in the mayor’s receptivity to the protests. “Last week (during the “mock” protest), the mayor invited an entourage of residents into his office to be heard,” she asserted. “Today, they locked the gates and called the police.”

Although police initially accompanied the peaceful demonstration, aggressive verbal confrontations began when protesters attempted to take over a multi-lane section of the major thoroughfare in front of City Hall. The arrival of a minibus carrying more officers marked a further escalation, as police began pushing elderly women out of the way.

Demétrio Martins, Horto resident and activist with the Favela Não Se Cala movement, who was filming the conflict, described that once the commander arrived, the police were able to exert disproportionate force against the protesters, none of whom were resisting.

The conflict led to the arrest of Popular Committee activist, Vitor Mariano. Speaking with reporters at the police station after his arrest, Mariano recalled that the police acted with excessive violence even as he submitted to the unfounded arrest: “I maintained that the people were within their right to free demonstration and he arrested me for disobedience and resistance [to arrest].” He was released a few hours later when video footage proved he had not violated any law.

Asymmetrical Media Coverage

Participants of Thursday’s protest were outraged that the Globo news network had covered the earlier “protest” extensively on TV and in print, publishing an article titled “Residents Request to Leave Vila Autódromo.” With reference to the image of the protest that Globo published (photo right), Sandra Isidoro da Silva, a long-time Vila Autódromo resident who wants to remain, commented: “That was a setup. Those signs are not ours and some of those people are not from Vila Autodromo.” In contrast, the Globo coverage of Thursday’s demonstration against removal was a one-sentence traffic notice noting that protestors had closed several lanes of Avenida Presidente Vargas and a brief two paragraph report.

Mainstream media coverage of the two protests points to an ongoing effort to ignore or delegitimize resistance efforts. The promotion of Parque Carioca housing and a spotlight on those residents wanting to leave are key strategies. Maria Melo observed: “When the protest is in favor of the City, they show it. When it is against, they don’t show anything, and last week this was very clear.”

Vila Autódromo’s Neighborhood Association President, Altair Guimarães, alleges that Globo intentionally ignores him: “They will say that I don’t answer my phone, but I spoke with them and invited them here today!”

Despite this invitation, a camera crew only arrived at the protest after the reports that an arrest had been made. Protesters and residents were so distrustful of Globo’s manipulation tactics that they decided no one should give an interview unless it would be aired live. Unable to comply and angered by the reactions to their presence, the reporters left the scene almost immediately.

Residents are enraged over the misrepresentation of the community’s wishes. The figures in Globo’s article on the October 30 protest, for example, falsely purport that only 27 of the community’s 600 families are still resisting the City’s proposal. However, a residents’ commission has been going door-to-door registering numbers accurately and in the first few weeks have already confirmed that 256 families want to remain.

Residents continue to hold weekly meetings in the community to fortify their struggle. On Sunday, November 10, the Archbishop of Rio de Janeiro, Dom Orani Tempesta, led a mass in the community in support of the resistance effort of those families that wish to stay.

Maria Lúcia de Pontes, a Rio de Janeiro State Public Defender from the Land and Housing Nucleus recently issued a statement that read: “The court ruling and legislation related to land tenure must be respected by the Rio de Janeiro city government, allowing families to finally live in peace with recognized land titles, urbanized streets, and public services provided.”