This is Part 4 in a four-part series on the History of Rio de Janeiro’s Military Police. Click here for Parts 1, 2, and 3.

It seemed as though, between the inauguration of the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) in 2008 and 2013, everybody held their breath. The police, while largely not identifying with a role they had been insufficiently trained for, in general performed their duties professionally, and there were few (reported) cases of corruption or violence. For their part, the residents of the affected favelas, though quick to point out the flaws in the program, reacted with cautious acceptance to it. The domestic media eulogized the drop in the homicide rates and the international media hailed a pioneering program.

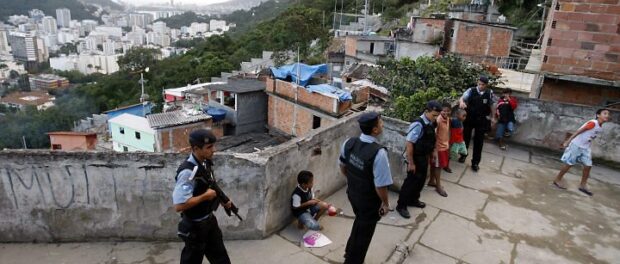

It is important to note that, despite all the recent criticism, there have been some positive aspects of the UPPs, particularly in the smaller favelas where community policing is, by nature, more likely to be successful. The most obvious change has been to reduce the rate of lethal violence within the favelas. Since 2005 the homicide rate in the city–a large percentage of which happens in the lowest income areas–has almost halved (from 42 per 100,000 to 24), and, just as importantly, police killings in the state have decreased from a record high of 1,330 in 2007 to 415 in 2012. Though this is not solely down to the UPPs, they have been a big factor. De-normalizing the propensity for lethal violence and the use of guns is hugely important in making Rio a safer place to live, and the UPPs have helped begin this process. Regarding this, perhaps the most potentially significant impact of the UPPs has been to give a generation of young children the opportunity to grow up in an environment in which drug gang violence is not the dominant feature of social control. The effects of this change may not be instantly measurable, yet they will surely have a positive impact in the future.

It is important to note that, despite all the recent criticism, there have been some positive aspects of the UPPs, particularly in the smaller favelas where community policing is, by nature, more likely to be successful. The most obvious change has been to reduce the rate of lethal violence within the favelas. Since 2005 the homicide rate in the city–a large percentage of which happens in the lowest income areas–has almost halved (from 42 per 100,000 to 24), and, just as importantly, police killings in the state have decreased from a record high of 1,330 in 2007 to 415 in 2012. Though this is not solely down to the UPPs, they have been a big factor. De-normalizing the propensity for lethal violence and the use of guns is hugely important in making Rio a safer place to live, and the UPPs have helped begin this process. Regarding this, perhaps the most potentially significant impact of the UPPs has been to give a generation of young children the opportunity to grow up in an environment in which drug gang violence is not the dominant feature of social control. The effects of this change may not be instantly measurable, yet they will surely have a positive impact in the future.

The installation of UPP units in favelas has also opened these spaces up for public services, businesses, organizations and civil actors which would not before have had the same opportunity or infrastructure to set up there. One of the key aims of the UPP was to regain some semblance of control of these spaces, giving state and civil actors the opportunity to bring much needed social improvements. Whether the expected improvements have been made is a question we will come to, yet it is undoubtedly true that the introduction of the UPPs has made the favelas much more accessible places, in all senses. There is now much more movement–in both directions–between the asphalt and the favela, and this new mobility, both physical and economic, of residents in pacified favelas, is, despite the associated increase in the cost of living, a positive development.

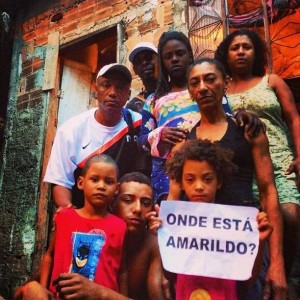

Yet despite these tentative signs of progress, it was fairly clear that the UPPs were functioning on a desperately delicate equilibrium. There was widespread skepticism in the program which only required one incident to turn into complete distrust. This came in July 2013, with the death, or rather murder, of Amarildo dos Santos whilst detained by the UPP in Rocinha. At this point, the fragile fabric on which the concept of the UPP had been built began to unravel. Though there have been many, many cases of police brutality over the last 25 years, because of the supposed philosophy of the UPP, and thanks to the new-found reach of favela resident voices through social media, this case caused particular outrage, and was made visible, in the wider community, both nationally and globally.

Yet despite these tentative signs of progress, it was fairly clear that the UPPs were functioning on a desperately delicate equilibrium. There was widespread skepticism in the program which only required one incident to turn into complete distrust. This came in July 2013, with the death, or rather murder, of Amarildo dos Santos whilst detained by the UPP in Rocinha. At this point, the fragile fabric on which the concept of the UPP had been built began to unravel. Though there have been many, many cases of police brutality over the last 25 years, because of the supposed philosophy of the UPP, and thanks to the new-found reach of favela resident voices through social media, this case caused particular outrage, and was made visible, in the wider community, both nationally and globally.

In the year since then there has been increasing protest against the UPP, for a number of reasons. Firstly, there is a sense that the police as an institution has not changed. Community policing is based heavily around dialogue and communication with the community, yet the majority of UPP officers’ activity is stopping and detaining suspects. Add this to numerous complaints of breaking down doors, entering houses without warning or a warrant and assaulting suspects and a picture is painted of a force whose policy is essentially the same, though less severe, as that which it intended to distance itself from. The brutal torture and murder of Amarildo by UPP officers, including a commander, only heightened this view.

Furthermore, there is a feeling that the police are trying to implement a social template on the favela by attempting to prohibit, or at least limit the cultural elements which they find inappropriate. One such example is the banning of baile funk parties, whilst allowing new club nights attracting “playboys” from nearby wealthy neighborhoods to flourish in the same spaces. The impression is sustained that rather than an attempt to integrate the favela into the formal city, this is state imposition whereby favela residents continue to be viewed first as a problem.

There is also a frustration that the program has failed to combat deeper social problems facing the favelas. The UPP is accompanied by UPP Social, which aimed to provide social and economic integration by, among other things, creating forums for discussion in the community, stimulating leisure and cultural activities and providing professional training programs for youth in the favelas. However, many of the UPP Social projects have had little impact, and in the eyes of many, including Ignacio Cano, an expert on public security in Rio, this is purely a policing program, with the social aspect little more than rhetoric.

There is also a frustration that the program has failed to combat deeper social problems facing the favelas. The UPP is accompanied by UPP Social, which aimed to provide social and economic integration by, among other things, creating forums for discussion in the community, stimulating leisure and cultural activities and providing professional training programs for youth in the favelas. However, many of the UPP Social projects have had little impact, and in the eyes of many, including Ignacio Cano, an expert on public security in Rio, this is purely a policing program, with the social aspect little more than rhetoric.

However, the major problem with the program is that it is essentially throwing a policing veil over areas which have deeply-rooted tensions with the institution as a whole. The overall concept of the UPP is not the main problem here; the problem is that it is being built on disastrously rotten foundations. The tensions between police and favela communities have been cultivated over the last half century (and more) and are unimaginably deep rooted. Though both police and residents lived, often reluctantly, with this tension for the first four and a half years of the UPP project, it was only a matter of time before it became too much. This is why there has been such an intensely violent recent reaction against the UPPs, despite them having an immeasurably better human rights record than other branches of the Military Police. The UPP project–with some modifications–was in theory a positive program, with the potential to change the face of public security in Rio; however, they are paying for the decades of neglect which preceded their existence. There was simply no way the same police institution which killed 1,330 people in Rio in 2007 could suddenly, drastically, transform its philosophy and expect citizens to instantly accept this reincarnation.

To even have a hope of re-shaping the perception of the police, these officers would need to spend at least a generation in the affected favelas, yet it is widely believed this will not happen. The UPP is simply too costly, too much of a strain on resources to be a viable long-term strategy. Many believe it will lack the political backing after the Olympic Games of 2016. State programs have historically been abandoned in the favela, and there is a natural fear that the UPP will be yet another to add to the list. This is a huge limitation: how can anybody, police or residents, invest faith in a program which they suspect will end having, at most, only partially solved the problems it set out to?

Because of the aforementioned planning, resources and money required to make the program work, the program will never (and does not aspire to) reach all of the city´s favelas. This leaves a dangerous double standard in which, in some favelas, the state promotes a peaceful solution based on mediation and communication, while at the same time, in others, it retains the war-like tactics developed by the police force over the last 50 years. Incidents like the killing of six supposed traffickers in Morro do Juramento the day after the death of a UPP officer make it feel even more like the UPP is a 21st century manifestation of Para Inglês Ver. In most of the 700 plus favelas in the city, the Military Police widely disregard human rights, earning the deserved reputation as one of the most brutal forces in the world.

Because of the aforementioned planning, resources and money required to make the program work, the program will never (and does not aspire to) reach all of the city´s favelas. This leaves a dangerous double standard in which, in some favelas, the state promotes a peaceful solution based on mediation and communication, while at the same time, in others, it retains the war-like tactics developed by the police force over the last 50 years. Incidents like the killing of six supposed traffickers in Morro do Juramento the day after the death of a UPP officer make it feel even more like the UPP is a 21st century manifestation of Para Inglês Ver. In most of the 700 plus favelas in the city, the Military Police widely disregard human rights, earning the deserved reputation as one of the most brutal forces in the world.

Meanwhile, the state is desperately trying to transform a handful of strategically selected favelas in the South Zone in order to present a sanitized version of the city to the masses and media who will descend for the World Cup and the Olympic Games (while the Baixada Fluminense, which has the highest homicide rates in the state, had its first UPP installed only this year). Further, since the first implementations, many have argued these locations were targeted for real estate speculation in the highly coveted beachside neighborhoods and, increasingly, the favelas that overlook them.

This strategy is embodied by the way in which the UPPs “retake” the designated territories. Notified weeks in advance that a community is to receive a UPP brigade, the organized drug groups which previously controlled these areas were given the chance–even encouraged–to flee before the entrance of the Special Forces Battalion (BOPE). Though taking their territory may weaken these groups, it certainly does not destroy them; rather it pushes them into another area of the city. This only serves to create a displacement of crime, yet perhaps this is the aim: the state would prefer to face criminals (and the bloody consequences) in more peripheral parts of the city. There is also speculation that the police may have forged a deal with the criminal groups. Whatever the case, it seems strange that Governor Sérgio Cabral, who in reference to combating crime once said “to make omelettes you have to break eggs,” would one year later be the driving force behind a program which essentially gives amnesty to criminals.

This strategy is embodied by the way in which the UPPs “retake” the designated territories. Notified weeks in advance that a community is to receive a UPP brigade, the organized drug groups which previously controlled these areas were given the chance–even encouraged–to flee before the entrance of the Special Forces Battalion (BOPE). Though taking their territory may weaken these groups, it certainly does not destroy them; rather it pushes them into another area of the city. This only serves to create a displacement of crime, yet perhaps this is the aim: the state would prefer to face criminals (and the bloody consequences) in more peripheral parts of the city. There is also speculation that the police may have forged a deal with the criminal groups. Whatever the case, it seems strange that Governor Sérgio Cabral, who in reference to combating crime once said “to make omelettes you have to break eggs,” would one year later be the driving force behind a program which essentially gives amnesty to criminals.

During the first four years of the UPP many, including this author, felt that the UPP, if managed well, had the potential to bring long lasting changes to public security in Rio. However, after the recent developments it is becoming increasingly tempting to adopt the cynical view of the UPP as a slick propaganda machine, complete with symbols, logos and internationally friendly slogans. In reality, the UPPs were simply too ambitious. Community policing is a commendable idea, yet the UPP has been implemented so quickly, on such a large scale, and in such an extremely volatile environment, that the problems it is facing were inevitable.

During the first four years of the UPP many, including this author, felt that the UPP, if managed well, had the potential to bring long lasting changes to public security in Rio. However, after the recent developments it is becoming increasingly tempting to adopt the cynical view of the UPP as a slick propaganda machine, complete with symbols, logos and internationally friendly slogans. In reality, the UPPs were simply too ambitious. Community policing is a commendable idea, yet the UPP has been implemented so quickly, on such a large scale, and in such an extremely volatile environment, that the problems it is facing were inevitable.

It seems that a more successful program can only happen after the two mega events. With all the anti-government feeling related to the exorbitant costs of the World Cup and the Olympic Games, there is too much unrest and cynicism to allow the UPP to function effectively. Ironically, though the World Cup and the Olympic Games gave the impetus to change security policy in the favelas, the cynicism which this has resulted in is a major obstacle for the program. Perhaps after these events have passed, the opportunity will arise to create a less politically driven policy.

Whatever this policy may be, it must include a restructuring of the Military Police. As we have seen over the course of this series, the Rio de Janeiro Military Police, throughout its history, has prejudiced and repressed the lower classes, becoming increasingly militarized in its policing of poorer areas of the city. It has resulted in a complete absence of trust between the favela and the state, which the UPP program has, almost inevitably, been unable to reverse. The only realistic way of restoring any confidence in the institution would be to completely overhaul the set-up of the Military Police, weeding out those guilty of corruption and lethal violence, creating an independent, well-supported oversight commission and ridding the still-existent military mentality that pervades. Until then, the conflicts and unrest currently flaring in pacified favelas seem set to continue.

This is Part 4 in a four-part series on the History of Rio de Janeiro’s Military Police. Click here for Parts 1, 2,and 3.

Patrick Ashcroft is a researcher currently based in Rio de Janeiro. His thesis on Rio’s Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) was completed as part of a Master’s degree in Contemporary History from the University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain.