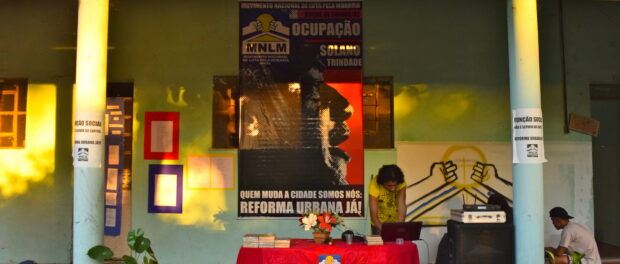

On Friday November 20, members and supporters of the National Movement of Housing Vindication (Movimento Nacional de Luta Pela Moradia, or MNLM) came together to celebrate the early successes of the Solano Trindade occupation in the municipality of Duque de Caxias in the Baixada Fluminense, as well as to discuss new strategies for the advancement of the occupation and betterment of living conditions for the families residing there.

The event, described as a “sarau divergente”–or divergent gathering–occurred on a date of symbolic importance, Brazil’s Black Awareness Day. Since its inception, the MNLM has hoped to tie its fight for social housing with the wider narrative of racial justice struggles both in the state of Rio de Janeiro and Brazil as a whole. Their Solano Trindade and Manuel Congo occupations in Rio are named after illustrious black Brazilians known for their contribution to the country’s racial justice struggles in the past.

Families and activists of MNLM occupied the property that currently makes up the Solano Trindade occupation on August 8. The land and buildings, which are managed by the Federal Union Patrimony Secretariat of Brazil (SPU) and used to house laboratories of the neighboring Pan-American Center of Aphthous Fever, had been abandoned and unused for 12 years when the movement occupied it.

Edivaldo, one of the new residents in the occupied land, stated that Solano Trindade was “completing four months of resistance” after having to overcome serious challenges from police and local authorities, standing strong in order to guarantee the “social function of property, as stated in article 182 of the Federal Constitution.”

MNLM sought to negotiate with the relevant government institutions since the occupation’s inception in order to officially legitimize their use of the abandoned property for social housing. Representatives from the movement had met with the SPU and the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA) and were in the process of establishing a deal when the occupiers were removed by the Military Police on August 21.

Eventually, the evicted families regained access to the occupation and have since legalized their status through negotiations with SPU and INCRA, though not without suffering intrusions from police forces intended to intimidate the residents.

“We already took the land, but the battle is just beginning,” with these words Gelson Almeida–lead MNLM representative in Rio de Janeiro–started off the presentation that constituted the main part of the gathering’s agenda. He then described the need to restructure the occupied space in order to foster “multi-use spaces” that can fulfil community needs for workspaces, living quarters and educational facilities.

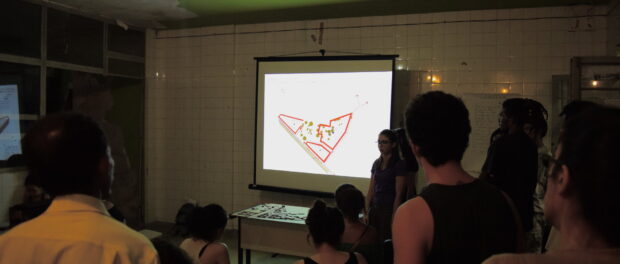

The “sarau” also had a presentation led by two architecture students from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) on potential methods of building new houses on the land and retrofitting old structures in order to maximize the amount of living space.

The students, both seniors who had chosen to work with the Solano Trindade occupation for their final university projects, presented a detailed analysis of potential revitalization strategies for the run-down buildings within the occupied property using technology and materials made in Brazil and typically utilized in building post-natural disaster relief housing.

After the student presentation, Almeida discussed at length the difficulty of gaining federal funding while preserving a sense of independence in building the community. The MNLM representative specifically criticized the Caixa Econômica Federal (Federal Savings Bank) specifications for social housing support, which dictate that projects such as Solano Trindade must follow the specifications of federal social housing initiatives to be financed by the government Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV) program.

According to Almeida, MCMV contains a series of stipulations that condition the aid it gives to citizens in need of housing. Details such as the building materials to be used in construction, the dimensions of new housing structures, and the companies and technicians to be consulted throughout the process would be decided without consulting the community if Solano Trindade chose to agree to the terms of the Federal Savings Bank.

The MNLM works according to the stated wishes and necessities of the community it strives to represent, according to Almeida, who states that “we won’t do anything if the community does not take part in the planning process.” MNLM occupations strive to create a communal living pattern, in stark contrast to what they perceive as the isolating effect of verticalized Minha Casa Minha Vida housing complexes. The families all contribute money for food, which they consume in a communal kitchen where a rotating list of volunteers cook meals four times a day. Some consumption costs are also split among the families, as is the responsibility for caring for and cleaning the space, as well as keeping it safe.

For the unique case of the Solano Trindade occupation, many of the federal demands not only present serious difficulties for the MNLM’s participatory operational model but also shut out several of the families from the federal benefits.

“The cut-off for social housing is a salary of R$1,600,” said Almeida. “which means if people who have been involved in the occupation process from the beginning now earn a bit more, they would not be allowed to live in Solano Trindade.”

Financial concerns arise from the funding stipulations as well. During their presentation, the UFRJ students said that the average cost of building a typical Minha Casa Minha Vida housing unit is R$76,000, while new units built with the materials and techniques they presented would average around R$40,000.

“Minha Casa Minha Vida creates no incentive for technical innovation,” said Ricelli Laplace, one of the two students who worked on the Solano Trindade case study. “It monopolizes the construction of social housing and doesn’t allow for new ideas.”

These complications show how much more of a fight still lies ahead for the occupation. The next step for MNLM leaders in Rio is lobbying for customized terms for the occupation in Caxias or finding alternative sources of funding. However, the financial constraints are just a few of a series of greater, if interrelated, obstacles.

Solano Trindade currently has enough housing capacity for ten families, but between 30 and 50 families show up to the planning meetings organized in the land’s communal space every 15 days. These are just some of the many families the MNLM keeps on a waiting list for housing in their occupations. As they wait for a spot, they receive orientation on their rights to housing and on the movement’s collective living model. Unfortunately, the scarcity of available occupied space means they have to prioritize access for those who need it most.

“If we posted a sign saying ‘Free Housing’ outside Solano Trindade, we would have 3,000 families lining up the next day,” said Almeida, discussing the movement’s need to carefully allot its available space.

Despite the continuing struggle to maintain and advance the occupation, residents took the opportunity to celebrate their achievements once the presentations finished. As night fell in Duque de Caxias, strings of fairy lights went up in the balcony of Solano Trindade’s main building, and the residents started blasting dance music on professional-grade speakers as another painted a mural of the MNLM symbol in the background. Later, children ran around the grounds while some of the older residents read poetry to an audience of residents and guests.

Throughout the event celebrating the occupation, as well as Black Awareness Day, many people present echoed Almeida’s closing statement: “It will be a long struggle, but it has not and will not be in vain.”