This is Part 4 in a five-part series documenting Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) Installations.

2013 was a crucial year for the UPPs. In the first four years of the program, the media, social commentators and public security experts had largely been supportive of the program, and positive results had been highly publicized. However, this year—the year before the FIFA World Cup—was the time at which deep cracks started appearing in the project. It became clear that UPP Social was not offering complementary support to the policing program, that vital public services beyond policing were not adequately reaching many communities, and that the ideal of ‘community policing’ was not being realized in those unstable areas most in need of security.

The 2013 implementations were largely carried out in the North Zone. As with the program in general, it was applied mostly in favelas dominated by the Red Command gang. Since pacification, favelas such as Manguinhos, Lins and Jacarezinho have seen numerous acts of violence, and police have failed to make communities feel safer. In Camarista Méier, basic services have not accompanied the increased police presence, while in Caju, revitalization projects have led to the threat of evictions. Though these areas have perhaps not presented the same difficulties as areas such as Alemão or Rocinha, they further stretched a program which was already facing mounting problems.

29. Manguinhos – North Zone

Date of Installation: January 16, 2013

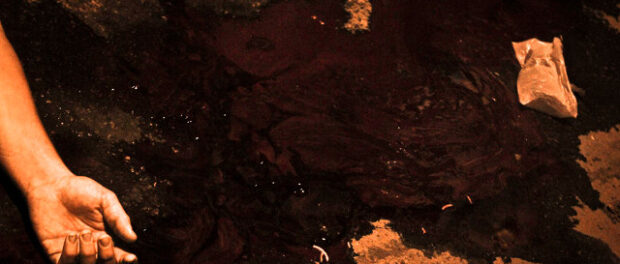

If one looked only at Manguinhos it would be difficult to believe in the potential positive impact of the pacification program. In March 2013, residents accused police of tasering Mateus Oliveira Casé, who died of a cardiac arrest after a confrontation with officers. Just two months after the UPP had entered the community, and a just prior to the Pope’s visit in the community, Mateus’ death was followed by scenes of protest. In December 2013, Paulo Roberto Pinho de Menezes died while in police custody, with officers attributing his death to a drug overdose; however, the autopsy revealed he had been asphyxiated, and five officers were charged with his death. And in July 2014, as a World Cup match was being played close by at the Maracanã, 25 year-old Afonso Maurício Linhares was refereeing a football match at which UPP officers detained a teenager for drug possession. In the ensuing confusion Linhares was fatally shot by the police. As well as lethal violence, since implementation the UPP unit in Manguinhos has been accused of regular acts of violence, arbitrary arrests and threatening residents with eviction.

Resident Perspective

“I am here [at a protest about police violence] because I live here, I grew up here, and my family has been here for over 40 years, and because I have a brother who is black. I am here because I am black, because I am a woman and because these aggressions keep repeating themselves. Even if I didn’t know the boys [who were murdered] personally, looking at them is to look at my brother. I am here because we don’t want this to happen again and we want to show this place has a voice.” – Monique Cruz, resident

30. Jacarezinho – North Zone

Date of Installation: January 16, 2013

One year and a half after the UPP was established there, in August 2014 Jacarezinho was the scene of one of the most shocking acts of police violence seen since the start of the UPP program. Three women were taken into a house by officers and raped, with one officer exclaiming during the act, “today you are going to see the devil.” When news of the group rape became public, Security Secretary José Mariano Beltrame lamented: “Unfortunately the police force isn’t immune to admitting people who will betray the mission to serve and protect.” Yet this type of abusive behavior is so common (if not always so extreme) that it cannot be treated as exceptional. The UPPs maintain a violent military character which manifests itself in the oppression of the poor. Further evidence of this came with the death in 2013 of Alielson Nogueira, shot as he ate a hot-dog during a confrontation between police and residents. As is so often the case in these communities, the police used lethal violence as a reaction rather than a last resort.

Resident Perspective

“They arrive with absurd authoritarianism, insulting people regardless of their age or physical condition. When they distrust somebody, even without any proof, they drag them out on the street, beating and pointing their weapons at nearby residents, as if everyone were a criminal. One day recently, an officer came into this alley and started waving his gun at residents. What is that about?” – Resident, 45 years old

31. Caju – North Zone

Date of Installation: April 12, 2013

Complexo do Caju, comprised of 13 different communities, was a first step towards the plan to pacify Complexo da Maré. Located at the northern tip of Rio’s Port region, Caju is one of the main areas affected by the ongoing revitalization of the port and residents fear that pacification is just the beginning of steps to force the removal of those from the community. It is in cases such as this that the UPP program starts to look like a cynical way of redeveloping the city, catering to private interests and repressing the poor. Residents say the communities desperately lack sanitation, health and education, a situation which greatly limits the possible benefits of pacification.

In policing terms, Caju has not been as problematic as many other implementations. Nevertheless, controversy hit in September 2014 when it was discovered that eight pistols had disappeared from the UPP unit. The prevalence of firearms is one of Rio’s biggest problems, and it goes without saying that this is only enhanced when police weapons find their way into the hands of criminal groups. One positive piece of news from Caju is that the community has received Canal Futuro from Senac RJ, a program designed to give professional courses in pacified communities and which has already reached almost 5,000 people.

Resident Perspective

“Why would you close schools and hospitals in the neighborhood with one of the lowest Human Development Index figures in the city? The movement should be reversed. Why does the governor send an invasion of the UPP and not an invasion of schools and hospitals?” – Myllena Cunha, community leader

32. Barreira do Vasco / Tuiuti – North Zone

Date of Installation: April 12, 2013

Compared to many of the other recent UPP implementations, Barreira do Vasco and Tuiuti have been much less problematic. Though historically controlled by the Red Command traffickers, it never saw the same levels of violence as some of the neighboring communities, and the presence of the UPP has rarely caused violent confrontation. Still, a policeman was shot in his car during an attack by traffickers in December 2013. The first significant protest came in March 2015 when a stray bullet (which some people claimed came from a nearby police chase) killed a resident, with protestors setting fire to a bus in revolt. Alongside the policing program, Barreira do Vasco has also received much needed investment in drainage systems, water supplies and roads, as well as five new plazas and reforms to two sporting centres. Although residents welcomed the investment, they regretted that the investments did not match the projects they had identified as priorities for their community.

Resident Perspective

“It has been a long time since this kind of thing happened. And it’s a really bad sensation, because we’re going to be worried about this over the next days.” – Resident who did not want to be identified, speaking after the December 2013 shootings

33. Cerro Corá – South Zone

Date of Installation: June 3, 2013

Located at the foot of Corcovado hill and Christ the Redeemer, Cerro Corá was an important strategic pacification due to its proximity to Rio’s number one tourist attraction. The UPP came in the wake of the Pope’s visit to Rio in 2013, and closed the “belt” of security between Tijuca and the South Zone. Public security expert Dr. Ignacio Cano was highly critical of the pacification there, citing the relatively insignificant amount of homicides that the UPPs would prevent, particularly when compared to Baixada Fluminense which has shocking murder rates yet only received its first UPP in 2014. A small favela with comparatively little tension, Cerro Corá was more evidence to confirm that favelas are primarily chosen for pacification because of their economic and touristic significance rather than because of their instability or the violence threatening their inhabitants. Pacification in Cerro Corá has been smooth, and there has been very little violence since implementation. The UPP has organized various successful events, including a debutante dance for girls from the community, and a group marriage under the statue of Christ the Redeemer.

Resident Perspective

“For residents, the presence of the UPP is insignificant. We won’t be affected at all. It should reduce the number of muggings in the surrounding areas. But the drug trade will always exist. What could end is the presence of weapons.” – Manoel Gomes, resident

34. Parque Arará / Mandela – North Zone

Date of Installation: September 6, 2013

The Facebook page of the Parque Arará Muay Thai group shows what can happen when the UPP is accompanied by social projects. In this case, officer Victor Silva took the initiative to organize a training group and the photographs from the Facebook page attest to its, and his, popularity with local children. Yet an incident from December 2013 shows a much more damaging aspect of UPP work and unfortunately seems more emblematic of the difficulties this unit has faced. While police detained a 13 year-old, residents tried to ensure that his mother accompanied him to the police station. In an attempt to diffuse the situation, a UPP officer fired a bullet into the air, which came down and hit 81 year-old José Joaquim de Santana in the face, killing him instantly. The UPP has not been well received in Parque Arará: in March 2014 a group of 150 attacked UPP containers, destroying five of seven containers and leaving scenes similar to a “warzone” in what was later reported as an orchestrated move by criminals. The Military Police moved quickly to reinforce police presence in the area, but pacification remains delicate.

Resident Perspective

“There is no doubt that today a ditch has opened. The situation was not easy from the start because of the history, the bitter memories of police abuse of power. Everyone knows that.” – Resident, speaking on the day de Santana died

35. Complexo do Lins – North Zone

Date of Installation: December 2, 2013

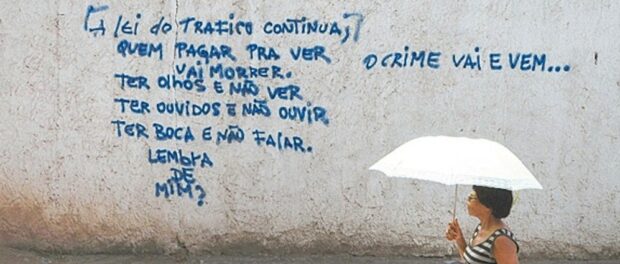

Although Complexo do Lins has only been pacified since December 2013, there is proof enough to conclude that the UPP is not working there. In February 2015 residents set fire to UPP containers, protesting after a 7 year-old girl was shot in a shootout. The following day journalists who visited the community were threatened by the police. In interviews, resident complaints were widespread, with many citing authoritarian behavior from UPP officers. These anecdotes serve as evidence that the program has degenerated both chronologically through the years and geographically as it has moved further north: between 2008 and 2010 there was an appearance that UPP police officers might have a radically different mentality than their predecessors, however that has since proved not to be the case. The UPP has limited control over Lins and drug traffickers have showed their strength in various attacks on UPP containers, setting fire to them at least 3 times in 2014. Sociologist Alba Zaluar believes residents are often pressured into confronting the police under orders from criminal groups, and this dangerous dynamic has left UPP Lins in an extremely precarious situation.

Resident Perspective

“They disrespect everybody. Women are called sluts. Youngsters are taken, tortured, threatened. It’s so much violence. Morro do Gambá, like all favelas in Lins, is fed up with so much arbitrary violence. Nobody here wants this. The UPP is a façade, a disrespect to the community. We need schools, day cares, a hospital, not the police.” – Márcia Jacinto, community leader

36. Camarista Méier – North Zone

Date of Installation: December 2, 2013

Camarista Méier has seen various cases of children with Hepatitis A this year, believed to be caused by the contaminated water supply. While this health problem cannot be attributed to the UPPs, it does show that there are extremely pressing sanitation issues that need to be addressed alongside pacification. In this video, Andre Luis da Silva highlights that a UPP unit means little without the provision of basic services. In a further interview, he claims the state has abandoned the community, leaving them without water and electricity, refusing to pave the roads, letting litter pile up and drainage problems worsen, and ignoring worries about the danger of landslides. In policing terms, Camarista Méier has not been a success. Attacks have left various officers hospitalized, while in October 2014 Elias Camilo became the eighth UPP officer to be killed. The State recently rated Camarista Méier with a “red flag,” making it one of six favelas classified as extremely unstable.

Resident Perspective

“They say they are going to resolve the problem, but it never goes past a promise. We have to buy gallons of water to be able to drink and make food. And when it rains a lot or is windy, to worsen matters, we lose our electricity.” – Alexandra Lucia Souza Mendes, resident, 31

This is Part 4 in a five-part series documenting Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) Installations. For other articles in the series click here.