The rise in Haitian immigration to Brazil has been hitting the headlines. According to figures from the Ministry of Work and Employment published by BBC Brasil, the number of Haitian workers in Brazil rose from 814 in 2011 to 14,579 in 2013. Justice Minister José Eduardo Cardozo declared that Brazil currently emits more than 100 visas a month to Haitians.

Thanks to a dynamic community leader, one favela in Rio’s West Zone is reacting to an influx of Haitian immigrants in creative and inclusive ways.

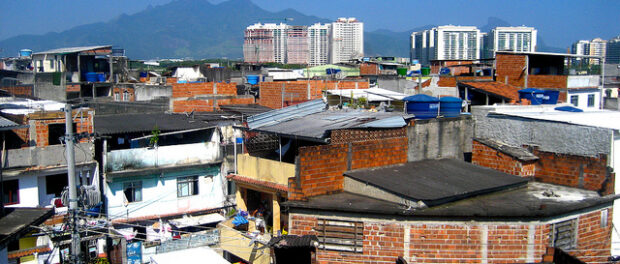

Home to 8,000 residents, over its 35 year history Asa Branca has witnessed the dramatic growth of the surrounding region, now peppered with huge developments including the main site of the 2016 Olympic Games. Skyscrapers loom large over the community, which sits in between the newly-launched TransCarioca Bus Rapid Transit line on one side and the still-in-construction TransOlímpica BRT line on the other.

Asa Branca’s Residents Association is celebrating its thirtieth anniversary this year, under the long-term leadership of its popular president Carlos Alberto Costa, known as Bezerra. Bezerra’s latest mission is to help improve the integration of the community’s approximately 150 Haitian immigrants, working in what Bezerra describes as the “boom in civil construction” in the Olympic Park region.

Bezerra saw Haitian immigration as an opportunity to increase integration in the community: “I said to myself: they’re here! They’re residents too. So we need to find out what they need.”

In May, the Residents Association welcomed Haitians, Brazilians and organizations working with foreigners in Rio for a traditional feijoada meal. “It was good! They came, they participated…we had a good chat,” Bezerra said.

He has recently joined forces with a Haitian resident to offer French and English classes in the community. Dieuseul Duclosil gave his first lesson to a handful of keen students on July 12 and Bezerra said he knew dozens of other residents interested in enrolling. He hopes this initiative will expand to include Portuguese classes for Haitians and has plans for a Haitian-Brazilian ball, with music from the two cultures.

Bezerra described how the classes came about: “[Dieuseul] has taught English and French before. And currently he’s unemployed… This is a way for the Association to help him.”

Dieuseul liked the idea. He said: “It’s good to integrate a nation that’s new here… [Bezerra] is a very interesting person, because he embraces everyone here. It’s not what you give someone that makes you a good person. It’s the way you think, the way you look at other people.”

For a favela that owes its conviviality and development to a dedicated community of long-term residents, the new Haitian neighbors represent a totally different way of living, based on years of migration. After the 2010 earthquake which devastated his home country, Dieuseul moved from Haiti to Ecuador, where he spent two years before moving to Rio Grande do Sul in southern Brazil, eventually moving to Rio in search of a hotter climate. “I said to myself: I’ve got to find a city where it’s hot, so I can live well!” he joked. He had been working in construction in Rio for over a year before being made redundant.

Other Haitian immigrants have similar stories of migration across several countries. Frisno Merat spent eight years in the Dominican Republic before moving to Brazil. He said he feels at home in Asa Branca: “Life is calm here, we don’t have problems with anyone here.”

His friend Lebien Prince agreed, showing off his young daughter, proud that she speaks good Portuguese. “It’s all good here, thank God, because right now I’m working. My wife’s here with me and she’s working too.”

The language teaching project is just one example of Asa Branca’s history of collectivity. The community built many of the services it uses today, including its sewerage system, created by residents some twenty years ago. “I’m proud of it; we’re proud of it,” said Bezerra. “And it still functions well. It was a sewerage system built for some thousand residents and now there are 8,000 of us, so it’s a bit complicated.”

Even so, Bezerra complains that the collective spirit in the favela is dwindling as he thinks residents have become more focused on self-improvement above community improvement.

He is trying to use his position as Residents Association veteran to motivate a new generation of community leaders and encourage participation and solidarity. With this in mind, he’s been holding a debate series, encouraging residents to come together to discuss issues such as racism, sexism and women’s issues, and the reduction in the age of criminal responsibility. “I know lots of people who are capable of doing a better job than me. You have to motivate these people, provoke them!”

Asa Branca’s Haitian residents know that their existence in the community depends on a source of employment, which is not guaranteed. In Frisno’s words, “you have to grab the work where you can find it,” suggesting that his next step might be São Paulo. And for Dieuseul, he says most Haitians want to return to their country. “We work, save money, to go back to our country. There’s no place you feel better than the place you were born.”

But while they’re living in Asa Branca, Bezerra will look for ways to include them in the community, “so they can have the dignity that human beings deserve, in a country they don’t know well.”