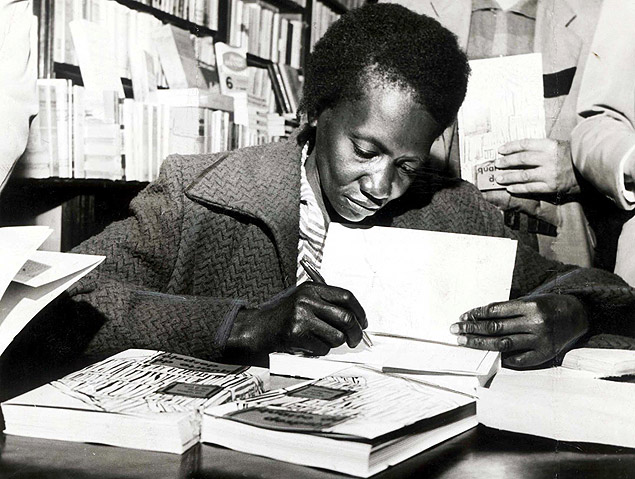

In honor of Brazil’s Black Awareness Month, the Afro-Brazilian Museum (Museu Afro Brasil) in São Paulo is showcasing an exhibition on the life and work of Carolina Maria de Jesus, Brazil’s only favela writer to be published in English during the 1960s. In 1958, pieces of her journal were discovered and transformed into her first book Quarto de Despejo, in English known as Child of the Dark, which has since been translated into 13 different languages.

The Carolina em Nós (Carolina in Us) exhibition contextualizes her life through panels, photos, and scenarios mounted on the side of the building and a free exhibition inside. Carolina Maria de Jesus’ work has received huge international acclaim and remains a testament to the struggle against poverty while highlighting the hardships inherent in life in São Paulo’s favelas at the time.

“I’m always nervous in the morning with the fear that I won’t make enough money to buy something to eat. But today is Monday and there’s a lot of paper on the street… Senhor Manuel came saying he wants to marry me but I don’t want to because I’m already getting on. And later on, a man doesn’t like a woman who can’t pass something [written] without reading it, and gets up to write, and sleeps with a pencil and paper under the pillow. This is why I prefer to live just for my ideals.”

Carolina Maria de Jesus was born in 1914, in the town of Sacramento in the state of Minas Gerais to a family of sharecroppers and slave descendants. Though Carolina suffered as the daughter of an unwed mother, she taught herself to read and write after attending primary school for only two years. In 1937, her mother died and Carolina migrated to the metropolis of São Paulo. In 1948 Carolina became pregnant by a sailor and, after being abandoned by him, moved to a favela. Carolina scraped together a living in whatever manner she could, often working as a maid, cook, and scavenging around her new neighborhood of Canindé.

Carolina, like many favela residents at the time, built her house using the materials she had available to her–metal, cans, plywood, and boards that she found in a nearby junkyard–with her child strapped to her back. Using her limited reading and writing skills, Carolina would record the day-to-day activities of her life in the favela. Neighbors felt increasingly uncomfortable at the thought of her writing about them, and treated her family poorly. As an independent woman she refused to adhere to certain social cues, refusing to marry because of the excessive domestic violence she witnessed and celebrating her Afro-Brazilian heritage, which was uncommon to do at the time.

“I wrote plays and presented them to the circus directors. ‘It’s a shame you’re black,’ they’d say. They don’t know that I love my black skin and coarse hair. I even think black people’s hair is more well-mannered than white people’s hair because black people’s hair stays where it’s put. It’s obedient. With white people’s hair, just a movement of the head and it falls out of place. It’s undisciplined. If reincarnation exists, I always want to come back black.”

Carolina’s diary included commentary on the details of the daily lives of “favelados,” or residents of favelas, and their struggle to retain their humanity in the face of overwhelming poverty. Carolina’s descriptions of poverty, hunger, and the fate of poor black women during the 1960s exposed a reality that otherwise was masked in all other literature of the time. Child of the Dark was never written to be published and instead was used by Carolina as a means of self therapy. The portrayal of her fellow favela residents, while informative for the rest of the world, alienated her from her entire community before she eventually left. Child of the Dark has been read extensively around the world, providing arguments for and against systems of capitalism and as irrefutable evidence of poverty as an insurmountable reality. She began to write her diary in the 1950s and explored issues such as housing, food, and medical care, among other human rights that continue to be a problem in favelas today.

Just three days after its initial publication, the first 10,000 copies had completely sold out in São Paulo. This caused an advance printing of 90,000 copies and hinted at the success Child of the Dark would have in the international arena. To put that into context, at the time Carolina even rivaled book sales from fellow Brazilian author Jorge Amado. Carolina’s other life work includes several other published books, hundreds of texts including poetry, plays, and carnaval marches.

Carolina’s main arguments throughout her work focus on the constant struggle of the poor to overcome their reality, and on to find food for her own family. She once said in her book, “and so, on May 13, 1958 I fought against current slavery – hunger!” Carolina fought her way out of poverty by every means available to her and though internationally recognized, was denied royalties by the publishing company for the translated versions and struggled to make ends meet up until her death in 1977.

Tamara David, coordinator of the Carolina em Nós exhibition, said: “Our intention is to recognize and give due importance to the figure of Carolina as a writer, not just because she was black or a picker of recyclable material, but for her valuable contribution to Brazilian literature.” Carolina lent her voice to those less fortunate. More than just a diary that showcases a mom’s journey to feed her children and avoid hunger, Child of the Dark was a cry for help that needed to be heard. As the writer of her own history, a single mother, and black woman, she portrayed a reality that can still be seen today.

Carolina em Nós runs until January 31, 2016 at the Museu Afro-Brasil in São Paulo. For more information click here.