Brazilian-born journalist Juliana Barbassa presents a stunning profile of the paradoxically beautiful city that is Rio de Janeiro in her first book, Dancing with the Devil in the City of God. The book, published in 2015, begins as Barbassa returns to Rio in 2010 after 21 years living abroad, bringing a unique combination of foreign and local perspective. The author had been working for the Associated Press while living in the United States when she moved back to Brazil and began work as AP’s foreign correspondent in Rio.

The book combines thorough historical context with engaging personal interviews to create an unapologetic portrait of Rio, one that embellishes the city’s attractions without obscuring its flaws. The majority of social, political, and economic developments covered take place with Rio’s preparations for the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics as the backdrop. Frequently, sporting mega-events inflate the pockets of a few at the expense of many, and as Barbassa discovers, favelas throughout the city have suffered extensively. Forced evictions, aggressive policing, and empty promises are just a few of the problems favela residents confront. Their collective plight constitutes a significant portion of the book.

Police occupations and UPPs

One of the author’s earliest moments of culture shock in Brazil occurs during her intense narration of the police invasion of Vila Cruzeiro, a favela bordering Complexo do Alemão in the North Zone. Upon seeing body bags leaving the battle, the author asks a police officer how many deaths there have been, to which he replies, “No one died… Just criminals.” Barbassa shows that this steadfast polarization of “us versus them” is reinforced with one of Rio’s many contradictions—by law, there is no death penalty, but “just looking like someone’s idea of a criminal” is enough for a security officer to justify murder.

One interview during the same Vila Cruzeiro invasion features a man who had been hit in the leg with a stray bullet, stranded on the street without a phone, money, or a way to walk up the hill back home to his family. He was bandaged by the hospital but still had the bullet lodged in his calf. The divergence from a policy’s stated purpose in theory to its application in practice is a frequent theme of Barbassa’s interviews and stories. Each Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) was supposed to disrupt the control of drug gangs in order to make communities safer; yet under the UPP units those who suffer most are often neither police nor trafficker.

In order to explore the full effect of the UPPs in Rio, the book turns to the South Zone favela of Santa Marta, the first “pacified” community. Local business association leader Andréia Roberto explains that without the drug gang’s control, businesses can register with the City and delivery trucks will bring inventory shipments all the way to one’s storefront rather than just to the bottom of the favela’s hill. Barber José do Carmo became known locally as the “Eike of Santa Marta,” in reference to the Brazilian billionaire Eike Batista, for the way he seized entrepreneurship opportunities following the UPP installation and legalized his business. But Leidemar Barreto, mother of six, saw her monthly rent payments rise from R$90 to R$180, leaving her completely dependent on the social welfare program Bolsa Família.

The anecdotes show the State’s willingness to offer a version of security to neighborhoods yet simultaneously make no effort to provide reliable access to utilities such as water, electricity, quality transportation, and more. Barbassa articulates this contradiction and dismisses the one-dimensional measures frequently used by policymakers to obscure the reality of life in favelas, such as a “purely economic definition of class” to prove that all UPP favelas had also been given a “middle-class quality of life.”

Evictions and removals

Barbassa gives a detailed account of select cases of community resistance to forced eviction for real estate development, a salient concern for many favelas as the city approaches the Olympics. Favela do Metrô, Aldeia Maracanã (not a favela, but an indigenous occupation), and Vila Autódromo are some of the main examples within this segment. The tone of the book’s narrative itself captures the initial sense of naive optimism towards the approaching Olympics as a potential “catalyst for change,” an attitude that slowly devolves into disappointment. In the same way, many favelas were optimistic about the city’s ambitious upgrading plans until “funding simply failed to materialize” and these promises were all withdrawn.

Promising ideas such as the favela upgrading program Morar Carioca or the community-produced proposals as alternatives to eviction consistently concluded fruitlessly at the hands of Rio’s government and its “state of exception.” What did emerge, however, was the power of community cohesion to combat unlawful treatment by the City. Barbassa’s stories of proposal and counterproposal, eviction and hollow justification, demonstrate a cyclical pattern. As the pre-Olympic urgency to meet deadlines intensified, these evictions began happening faster and more often. Some stories end painfully unfairly, but Vila Autódromo offers a powerful precedent by retaliating with social organization. This mega-event chapter of Vila Autódromo’s decades-long struggle to remain continues today, and remains an exceptional success against land developers.

Inequality continues

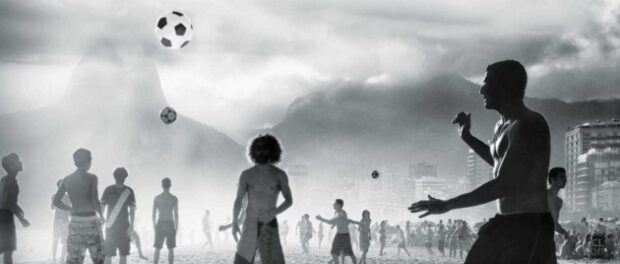

The World Cup and the Olympics presented an opportunity for the city of Rio to address countless social and economic issues that have plagued the city for generations. As the World Cup came to a close, not only had Brazil not found glory on the pitch but these same essential issues had still not been solved, awaiting acknowledgement from a defeated Brazil. The final chapter of Barbassa’s book describes the nationwide identity crisis after the 7-1 loss to Germany, in which Brazilians question their reputation as the país do futebol—the country of soccer. When the book concludes, two years from the Olympics, and through to today, just a month from the Games, these same questions of addressing the city’s inequalities are as pertinent as ever.

In an interview from June of this year, the author describes the city as “one that I think is more unequal than the city that we had before these mega-events,” yet the hard times are prompting civil society, from everyday citizens to organizations–including favela residents citywide–to fight for more positive transformations by demanding their basic rights.

Juliana Barbassa is currently in Rio de Janeiro observing the impact of the Games and writing for a number of outlets through September. In Brazil, Dancing With the Devil in the City of God is available at Livraria Saraiva.