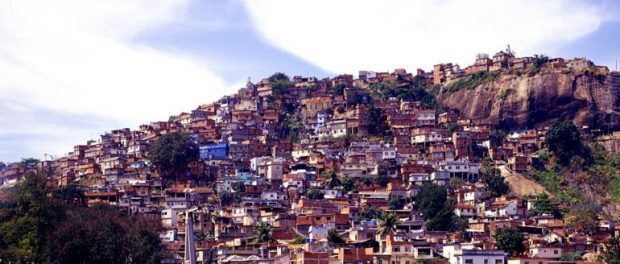

For a long time favelas were adrift from the debates at the heart of this city, thought of as marginalized and wrapped up in violence and poverty. Their residents forever carried with them the weight of a stigma related to living in a certain part of the city. The translation of the term favela in a well-known dictionary still defines “favela” as a group of disorganized and ramshackle constructions where poor people live.

There was a great effort to keep favela residents right there, in the favela, given their values and ways of life were seen to be distant and disassociated from the elitist context. The value and acceptance of a favela resident resulted only from their ability to perform hard work. Only if they worked hard and well did they become more accepted according to the social norms of the broader city. From the tone of their voice, to how they walk and sit to table manners and etiquette, even today there are still many things a favela resident has to learn in order to be accepted in certain places.

A little while ago, this changed and the favelas became the center of attention in certain spaces. Their culture started to be consumed, recognized and even appropriated by some. They became an object of research and people from all over the world came and took an interest in their history, how they are organized, their customs and their values. They transformed the favela—once a symbol of violence, exclusion and marginality—into a sellable and acceptable product. It became hip to wear havaianas, the cheapest and most reliable flip-flops, mainly worn by poor people. Favela funk music was modified, to such a point that it became acceptable and very present in the lives and parties of the city’s rich. The favelas now commanded a price, but they did not lose their values.

The multiplicity of people, lives and stories that exist in the favelas make it impossible to say what a favela is or what it is not. The fact is that with all of these eyes now focused on the favelas and all that appetite to define or describe what happens in each alleyway and on every street, some stigmas were addressed while others were constructed. The result leaves it unclear: it is as though one person reading a description of a favela would find it completely coherent, recognizing and identifying with it, and yet another person reading the same text would not understand it at all.

The favelas should not be thought about as something exotic, distanced from reality or pitiable. Favela residents carry with them the strength and energy to transform realities. I like to say that almost every favela resident is an activist, because resistance precedes activism, and the only thing that defines the favela context is struggle and resistance.

“Favela” is the name given by the State to the irregular grouping of irregular buildings. But it is also a place where residents organize themselves in autonomous community away from a city planning and management process that does not recognize society’s poorest and that has consistently denied them their basic rights.

Stigmatizing favelas and other poor communities can cause serious damage. The media does this every day by reporting only on how dangerous certain areas can be and creating an atmosphere of fear. Businesses lose out because no one wants to go to a place where they could lose their life.

The favela isn’t by nature violent or dangerous, the police is.

Daiene Mendes is a 26-year-old resident of Nova Brasília in Complexo do Alemão, communications intern with Amnesty International Brazil and creator of the project FaveLÊ.