On Tuesday, March 14, RioOnWatch visited Vila Autódromo, the community that became internationally known during its determined fight against evictions due to its proximity to the Rio 2016 Olympic Park. Those residents who fought to the end and were ultimately allowed to settle in the newly built replacement housing on site are now well-organized and ready to receive–and inspire–visitors.

After years of community struggle against evictions, one broad asphalt road with government-built identical white homes housing 20 families is all that’s left on the land once occupied by the vibrant community of Vila Autódromo, originally with 700 families.

The first house on the street, now called Rua Vila Autódromo (Vila Autódromo Street), is home to Sueli, who immediately reported that the evictions have impacted her financially, as well as socially: “I used to live in a house twice as big, which also functioned as my restaurant and catering service.” With resilient spirit, she and her neighbors are each tailoring their identical government-issued units to meet their particular needs and tastes. The front of her home will serve as a new restaurant.

Sandra Maria, resident and activist, leads a group through the street, pointing out the poor construction quality by the government: “we hoped that once we had paved streets, we wouldn’t have puddles of rainwater,” which serve as breeding grounds for mosquitos, only increasing infection risks.

While pointing towards the unused gravel parking lot surrounding Rua Vila Autódromo, where homes were removed to ‘make place’ for the Olympic Park, Sandra explains that the abandoned area “illustrates the governmental mechanism of evicting residents and then abandoning places, ultimately transferring areas for capital development.” One of the claims historically made by the City for evicting residents from the community is rooted in environmental discourse, yet “trees were the first things to be cut down during the evictions.” The City had effectively converted a tree-filled community into an abandoned car park.

As a result, one of the community’s primary current efforts is to reforest Vila Autódromo. Sandra explains that once the Olympics came “everything was a concrete jungle: paved streets and a few white houses.” As a result community members have worked hard to plant trees and have opened a small playground in the gravel lot.

Preserving Memories

After visiting the homes and turning the one corner on the street, we arrived at São José Operário Catholic Church, an original building allowed to remain, thanks to community efforts. Since the church was an established structure next to the street that was rebuilt with residences, it would not be difficult to maintain. This, along with the two fresco murals, recently painted thanks to an initiative by Brazil’s Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), helped strengthen the residents’ case to maintain the church.

The church played a crucial role in Vila Autódromo’s resistance movement and continues to do so today, providing remaining residents with a reference point tying the land back to the original site. The church, built by residents, always kept its doors open, standing firm during evictions and hosting community meetings and even providing temporary shelter for community activist Maria da Penha, known as “Penha,” when she was removed from her home due to the eminent domain decree, but nonetheless refused to take compensation.

According to Penha, the church continues allowing them to host groups including universities, activists, journalists, and NGOs who come to learn from community members about their resistance efforts.

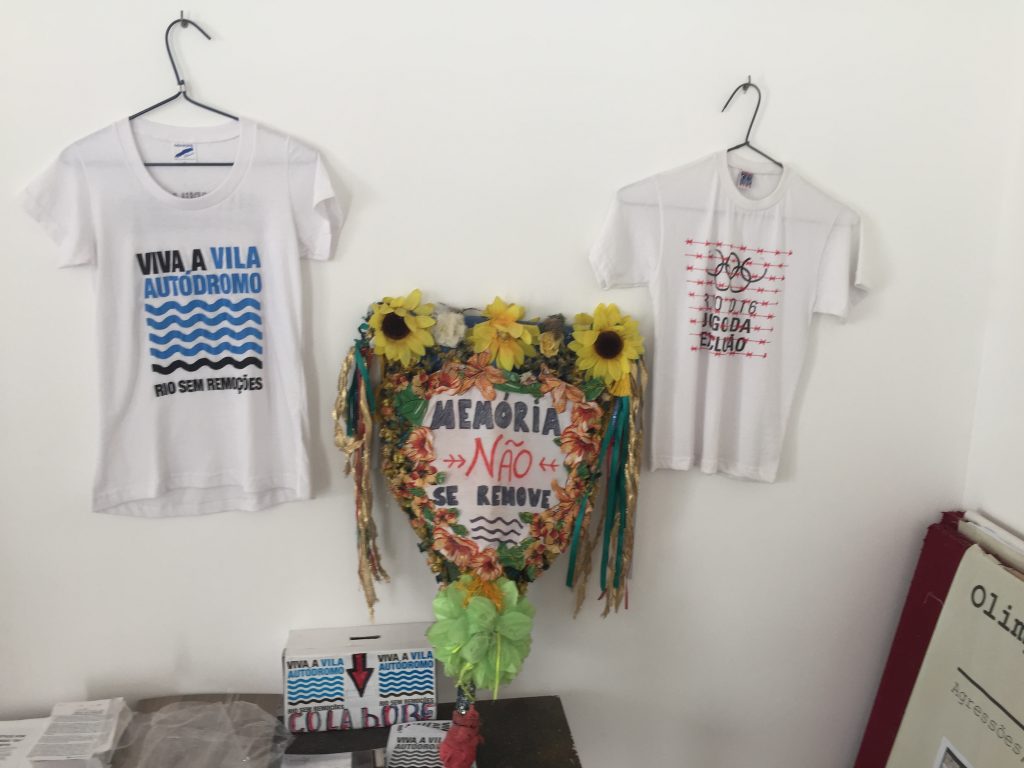

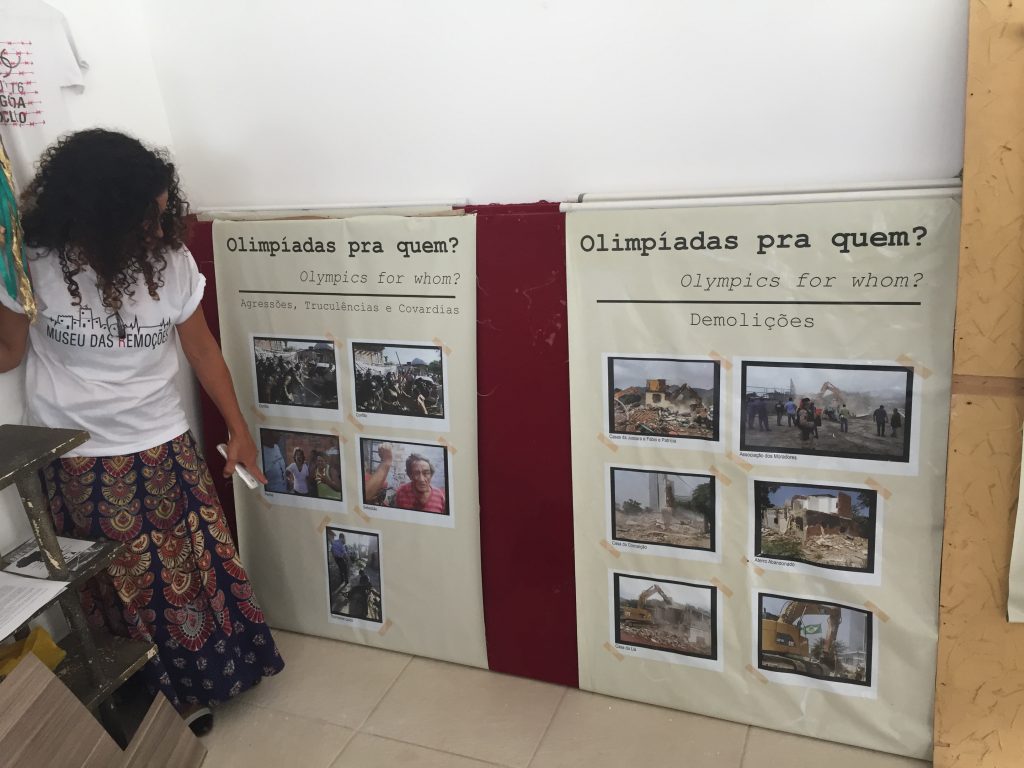

These resistance efforts convalesced into the launch of the Evictions Museum last May. The Evictions Museum has become Vila Autódromo’s primary post-Olympics organizing tool. Though the entire original community’s land is contemplated in the open-air museum, it also includes numerous archives storing the memory of the community in various forms. Currently, Penha’s house has been converted into a temporary exhibition space with photographic exhibitions and materials.

Model in a Global Fight

Those twenty families who successfully withstood the trials and tribulations of the pre-Olympic evictions process believe they are now safe from future threats. They continue emphasizing that the area was decreed an Area of Special Social Interest for Housing under Municipal Law 74/2005, and that they’ve received 99-year leases from the State government. However, the City government has not yet provided the formal promised papers recognizing their ownership of the new homes. Nor has the City completed the remaining infrastructure promised to the community.

That said, most emphasized by Penha and Sandra is the global nature of their struggle, and their availability to support activists elsewhere. According to Penha, “it’s not finished… it’s an ongoing struggle worldwide and through global networking and using social media we can bring the story to others.” Sandra was invited to participate in the Habitat Conference in Ecuador, while Penha has traveled with Amnesty International to Washington and The United Nations in Switzerland to deliver testimonials.

That said, most emphasized by Penha and Sandra is the global nature of their struggle, and their availability to support activists elsewhere. According to Penha, “it’s not finished… it’s an ongoing struggle worldwide and through global networking and using social media we can bring the story to others.” Sandra was invited to participate in the Habitat Conference in Ecuador, while Penha has traveled with Amnesty International to Washington and The United Nations in Switzerland to deliver testimonials.

Using social media and their intimate knowledge of resistance strategies, and with help from a network with other communities, Vila Autódromo’s remaining residents seek to mobilize others: “we receive emails, videos and visits from communities all over the world… With our knowledge now we can help others… We are now sharing material with Tokyo where the next Olympics will be held,” Penha explains.