An explosion of color. Glitter, sequins, feathers, infectious music and of course samba dancing cue the start of Rio de Janeiro’s Carnival 2018. But this year it’s Carnival with a difference—a huge lack of funding. Mayor Marcelo Crivella slashed funding for this year’s iconic samba parade and festival. The evangelical bishop has been accused of harboring deeply negative feelings towards African religions and targeting Afro-Brazilian culture, which are at the root of Rio’s carnival.

Samba, Brazil’s most iconic musical style, celebrated its centenary last year (the date that marks the recording of the classic, ‘Pelo Telefone‘) but today, as was the case 100 years ago, the infectious rhythms are the subject of tight restrictions and are often criminalized, with many events across the city being stopped by the police or closed down altogether.

Rio de Janeiro is the epicenter of samba, its cultural home. Samba’s lyrics often depict the deep inequalities and oppression experienced by many of the city’s residents as well as by manifestations of African culture. A culture passed down through generations since 2 million of their ancestors arrived in Rio’s port, and others in Brazil, for a total of 4.8 million enslaved Africans brought to the nation (10 times the number that arrived in the United States).

The traditional samba parade at Rio’s purpose-made Sambadrome is the most high-profile event to be affected by Crivella’s complicated relationship with popular Afro-Brazilian culture. The technical sessions, which usually attract around 50,000 people, were cancelled this year due to a lack of funding. These practice sessions give Rio’s lower-income citizens the opportunity to see legendary schools like Salgueiro, Portela, and Mangueira, when they cannot afford to buy the costly tickets for the official parade. The rehearsals have been mandatory for the Carnival program since 2002 and enable the samba schools to test light and sound as well as perform their routines down the Sambadrome track.

The public funding cut is a gigantic 50% drop in support for the main samba schools, with each school receiving R$1 million down from an annual R$2 million. Crivella has suggested that the League of Samba Schools (Liesa) seek private investment to plug the shortfall, despite Rio carnival’s “private” funding traditionally involving heavy investment from organized crime.

The samba schools feel betrayed by Crivella, who during his campaign promised to maintain the support that the previous administrations gave to the parades, and even hinted at increasing support. In a statement, the municipal body responsible for the parades, Riotur, said that “the development of mechanisms for attracting investments from the private sector to carry out the parade of samba schools is under study.” According to Crivella, this will come into force for the 2019 parade. “We will have a spectacular Carnival next year, with more private than public funds,” said the mayor.

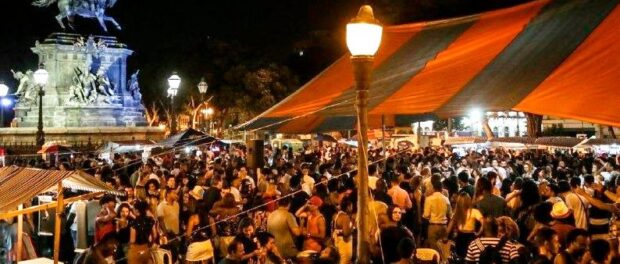

But unfortunately the crackdown on culture doesn’t stop there. Rio de Janeiro’s diverse Afro-Brazilian music culture, including street samba, has experienced a raft of closures and bans over the last few months. Incidents of police closing or attempting to close events include Carnival bloco (street party) rehearsals at the Aterro do Flamengo in October and other events in Rio’s West and North Zones such as at the Carioca Arena Dicró in Penha. The popular Passinho Carioca group planned to end its season at the Arena with a big show, but the event was canceled by order of the Military Police. Producers and regular attendees claim there was no justification or warrant for action.

These closures happened after a new decree was introduced by the City in May last year which makes it more difficult for street events to obtain a license. In a video posted on his website, Mayor Crivella denied that the purpose of the decree was to prohibit Afro-Brazilian religious activities in the city. “That [would be] completely unconstitutional and even if it were not, I would not do it,” he said. After a wave of criticism, one court has ruled that the decree is, in fact, unconstitutional.

Felipe Duarte is a samba producer and organizes samba circle events across the city. He has noticed a huge rise in the number of closures and his event in Praça Tiradentes, Pede Teresa, has been closed down by the police.

“In addition to Pede Teresa, there have been problems at events in Madureira Park, Pedra do Sal, and also [with the Afro-Brazilian bloco] Tambores de Olokun. Each one with a different justification, however, always involving the City or the police. In our case, the Military Police claimed that our Roda da Samba stimulated a growth of violence in the area, due to the flow of people after the event, thus attracting thieves profiting from this situation. Obviously, culture cannot be blamed for violence. The responsibility lies with the State, which must protect us, respect us, and prepare for any security demands.”

Duarte claims that additional information sourced from the Military Police showed that 75% of the crime in that locality occurs after 4:30am. “There was no plausible justification for the ban, as our samba ends at 12:30am. We were extremely frustrated by this situation.”

But there could be light at the end of the tunnel. A new law was passed last year—the Gamarra Law named after Pablo Amaral, known as Gamarra, a well-known and respected samba musician who passed away suddenly last year at just 37 years old. Recognizing the cultural value of samba, the law calls for the preservation and promotion of the genre. Duarte is hopeful, but knows that this won’t be a panacea: “Certainly the law will help. My wish is that this law will preserve the memory of Pablo and guarantee the sovereignty of Rio’s samba, as he always defended it. May samba follow the path that Gamarra helped to build, and many other sambistas who have been writing this story.”

He continued: “This situation is extremely important. Samba musicians are demanding, seeking protection, raising awareness and support. As a sambista and lover of popular culture, I am one of those who rebukes [Crivella’s] management of the city and I also believe that religious interests can interfere in some of his decisions.” According to a October poll by the DataFolha Institute, Crivella’s approval rating among Rio residents is just 16% while 40% disapprove of the evangelical mayor.

One of the most recent impacts of Crivella’s clampdown on religious and cultural activities was the indefinite closure of Casa do Jongo da Serrinha last month. The traditional cultural house in the Madureira neighborhood, which hosts popular Afro-Brazilian dance classes and jongo circles, was forced to close because funding from the city government was cut. Casa do Jongo is not just a cultural space—many consider it the heart of the community. Funding cuts made by the Crivella administration are not just about stopping street parties or the traditional samba parade—they are systematically targeting Afro-Brazilian cultural projects that are the lifeblood of the city.

Crivella will reluctantly attend this year’s Carnival parade. Meanwhile, beyond cultural manifestations, human rights are also being implicated by the mayor’s antagonism: the growing intolerance towards Afro-Brazilian religious practitioners and culture are driving the persecution of their followers, with those groups bracing for more devastating violence in the year ahead.

Crivella has been in office for only a year, while Afro-Brazilian culture has been a cornerstone of life in Rio de Janeiro since the city’s founding.