“The favela is not just a place,” explains Ricardo Rodrigues of Cerro Corá, in Rio’s South Zone. “It is an idea–of deconstructing life, of resilience, of understanding oneself as part of this space.”

Wearing a t-shirt reading “Favela Carioca” that he himself designed, Rodrigues’ outfit is just as conspicuous as his ideas as he speaks of the inspiration for his exhibition “Favelando,” which was displayed at the Oduvaldo Vianna Filho Cultural Center from June 23–August 5.

Wearing a t-shirt reading “Favela Carioca” that he himself designed, Rodrigues’ outfit is just as conspicuous as his ideas as he speaks of the inspiration for his exhibition “Favelando,” which was displayed at the Oduvaldo Vianna Filho Cultural Center from June 23–August 5.

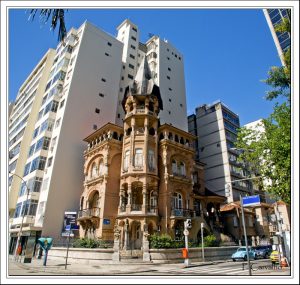

The space hosting the exhibition, commonly known as the “Castelinho do Flamengo,” is situated in Flamengo across from the Aterro do Flamengo, one of the largest public recreation spaces in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone. The decadent mansion was originally built by a renowned 20th-century Italian architect for a wealthy Portuguese businessman. Today, it serves as a cultural center that has hosted countless cultural exhibitions and displayed a wide array of local artists.

Rodrigues’ exhibition challenges not only viewers’ perceptions of favela residents but also of the favela’s place in the city. By presenting artwork that not only depicts favelas but that comes from favelas—and is produced by favela residents—in what has historically been an elite space, Rodrigues inverts the favela’s place in art: from object (favelado) to subject (favelando).

The exhibition contained two large spaces: one with Rodrigues’ own artwork, colorful paintings of daily life in a favela and remembrances of his childhood, and in the other a massive model of a favela, constructed out of cardboard, string, and other reclaimed materials by children from local favelas. Hanging on the wall next to the model is a picture of the children, aged six to twelve, constructing the model.

Rodrigues’ paintings are visually striking and worth visiting on their own; it is clear, however, that his greatest passion lies in working with children, inspiring them to create while also inspired by their creativity. Here, Rodrigues’ mission is as social as it is artistic. He values the art not only for the end product but for the process of creation, which he sees as a vehicle for healthy and transformative development, especially for children.

“Art was a tool that rescued me from becoming engaged in, and for keeping my friends from, getting involved with [certain things]—[to keep] children from going down the wrong path and getting involved in drug trafficking and other things. I think that art has this very positive power to offer another path, another direction. At a certain point in life, children become adolescents. When they have contact with art before this point, they become different people.”

“Art was a tool that rescued me from becoming engaged in, and for keeping my friends from, getting involved with [certain things]—[to keep] children from going down the wrong path and getting involved in drug trafficking and other things. I think that art has this very positive power to offer another path, another direction. At a certain point in life, children become adolescents. When they have contact with art before this point, they become different people.”

But for Rodrigues, art is not only critical for child development but is also a much-needed escape. In many of Rio’s favelas—where children often must navigate power dynamics between a militarized police force and drug traffickers, where even school uniforms do not protect them from police violence—childhood and the concept of “play” are often fleeting.

“Everyone grew up, and I wanted to remain a child—to ‘play’ like this,” Rodrigues explains. “We need to give new pathways for these children. They don’t need to ‘grow up.'”

In the final weeks of the exhibition, the children who created the model visited the Castelinho and saw their work displayed for the public. Coming from several favelas, including Rodrigues’ home of Cerro Corá, the children were able to see themselves represented in an unexpected environment. As Rodrigues and an employee of the Castelinho explained, the children were able to see: “I belong to this space and this space belongs to me. I am part of this history.” The visit, and the “Favelando” project in general, the employee explained, provided a bridge for crossing the divide between the “morro” and “the asphalt”—between the favela and the formal city.

In the final weeks of the exhibition, the children who created the model visited the Castelinho and saw their work displayed for the public. Coming from several favelas, including Rodrigues’ home of Cerro Corá, the children were able to see themselves represented in an unexpected environment. As Rodrigues and an employee of the Castelinho explained, the children were able to see: “I belong to this space and this space belongs to me. I am part of this history.” The visit, and the “Favelando” project in general, the employee explained, provided a bridge for crossing the divide between the “morro” and “the asphalt”—between the favela and the formal city.

For Rodrigues, the divide is superficial. “Everything comes from the favela… The favela has great importance.” As his work shows, there is at least as much creativity, productivity, and joy in favelas as in the formal communities they overlook.