On October 28th, Brazil elected its next president, far-right nationalist Jair Bolsonaro of the Social Liberal Party (PSL), in a decisive victory over Workers’ Party (PT) candidate Fernando Haddad.

Remarkably, Bolsonaro forged his path to victory by winning the votes of groups that he consistently derided. In a majority mixed-race country, a man who claimed that some black people are not “even good for procreation” consistently led opinion polls among black and brown voters, up until the final poll the day before the election. A man who once told a female member of Congress, “I would never rape you, because you don’t deserve it,” similarly led women up until the eve of the election. After years of corruption, violence, and recession, many Brazilians are simply desperate to try something different.

Beyond clamor for change, Bolsonaro surged with the backing of new or emergent forces that kept him above water following incidents and statements that would ordinarily be considered disqualifying. New technologies enabled campaigning outside of Brazil’s heavily regulated campaign framework. New or increasingly powerful coalitions emerged—ones willing to look past Bolsonaro’s fire-breathing so long as he delivers on their key priorities. In this article, we highlight four new and emerging forces that shaped this year’s elections: digital illiteracy and “fake news,” WhatsApp, anti-Workers’ Party sentiment (antipetismo), and evangelical churches.

Digital Illiteracy and “Fake News”

In an all-too-familiar echo of elections around the globe, the proliferation of lies and intentionally misleading stories in Brazil facilitated the rise of an extremist and contributed to a marked increase in political hostility and polarization. Slandering political enemies is a tactic older than democracy itself, but the mass adoption of online social media enabled smears and rumors to spread with speed and achieve unprecedented reach.

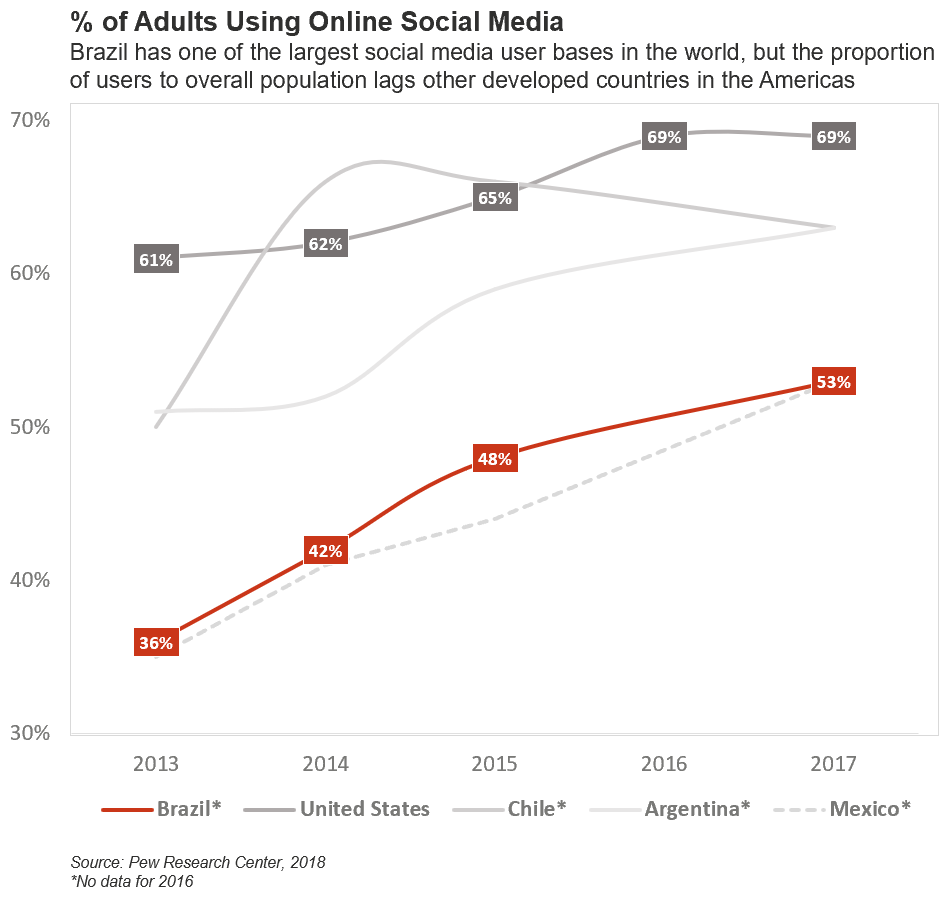

There exists an unwelcome reality at the heart of this crisis of misinformation: it can be extremely difficult to discern fact from fiction. While informed voters can pick out the most outlandish examples of fear-mongering, even the digitally-savvy have difficulty judging the legitimacy of news sources and identifying information that is false, and yet believable. Furthermore, being informed and digitally-savvy is a significant hurdle that the average Brazilian voter often does not clear. Over half of Brazil’s voting population has not completed high school, and widespread social media usage is a very recent phenomenon—even more so than the U.S. or regional neighbors. As seen in elections around the world, voters are unprepared and under-educated on how to safely navigate this digital frontier. Unfortunately, Brazil’s demographics only make it more susceptible to misinformation.

While some groups intentionally take advantage of digital illiteracy by planting false stories and conspiracy theories, misinformation campaigns cannot be truly effective without their transmission vectors: well-intentioned, unsuspecting people. Social media can make individuals feel like they’re receiving news from trusted sources like friends and family. The spread of misinformation is not always malicious; oftentimes, it simply takes the form of people passing on information they deem meaningful to those close to them.

WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned messaging platform used by nearly 60% of Brazilians, became the primary channel through which misinformation is spread—particularly after Facebook introduced new security measures designed to prevent and remove fake news. It is particularly fertile ground for sowing deception: almost every Brazilian with a smartphone uses it, oversight without violating user privacy is extremely difficult, and its message-forwarding and group-creating functionalities make it easy to reach huge audiences with just a few taps.

Brazilians have used WhatsApp to share political stories, videos, and memes for years. However, the app took center stage in these elections. “This year [the spread of fake news on Facebook and WhatsApp] was very sinister… it effectively feels like a digital war,” lamented Andres Souza, a 29-year-old resident of Rocinha. “In 2014, during the election of Dilma [Rousseff] against Aécio [Neves], we already debated politics on Facebook, we already sent things on WhatsApp… from there, it’s grown more and more. Specifically WhatsApp, I can’t take seriously.”

Fake news and its perpetrators exist on both the Right and the Left, but Bolsonaro, whose national profile exploded despite being almost completely locked out of TV and radio advertising in advance of the first round of voting, was the prime beneficiary of (mis)information spread via WhatsApp. On top of unsuspecting citizens, Bolsonaro received support from powerful and wealthy sources that deliberately planted misinformation to help him. An explosive report by the Folha de São Paulo exposed an illegal multi-million dollar operation spreading false anti-Haddad propaganda on WhatsApp. Additionally, a meeting between one of Bolsonaro’s sons and Steve Bannon, U.S. President Donald Trump’s former campaign strategist, led to speculation that he advised Bolsonaro’s campaign on the strategic use of media manipulation and social media.

Anti-Worker’s Party Sentiment

Jair Bolsonaro’s story is inextricably intertwined with the rise and fall of the Workers’ Party (PT). His ascendancy is less about the sweeping embrace of his militant ultra-conservatism and more about venomous contempt for the party that led Brazil for most of the 21st century. This contempt breeds from the feeling of betrayal many experience, given that the Workers’ Party was seen as representing the masses, yet was the party most marred by the Lava Jato (“Car Wash”) corruption scandal.

Distaste for the Workers’ Party, or antipetismo, has grown since the party’s inception in 1980. Originally sourced in class conflict, antipetismo grew through fear-mongering spread by opponents and more recently by corruption (though some attribute this not to its central role in the corruption scandal, but to Brazilian media representation of it as such).

While antipetismo was a weak force during the economic boom days of Lula, much of the Workers’ Party social and economic legacy has since crumbled under the weight of the Car Wash scandal, the economic crisis, and the humiliating downfalls of the party’s standard bearers (Lula, jailed on corruption charges; Dilma, controversially and undemocratically ousted from office). As Brazil’s economy burns and growing levels of bloodshed soak its streets, citizens from all walks of life—fairly or unfairly—directed their anger at the Workers’ Party. This, combined with a flood of misinformation, drove a surge of antipetismo.

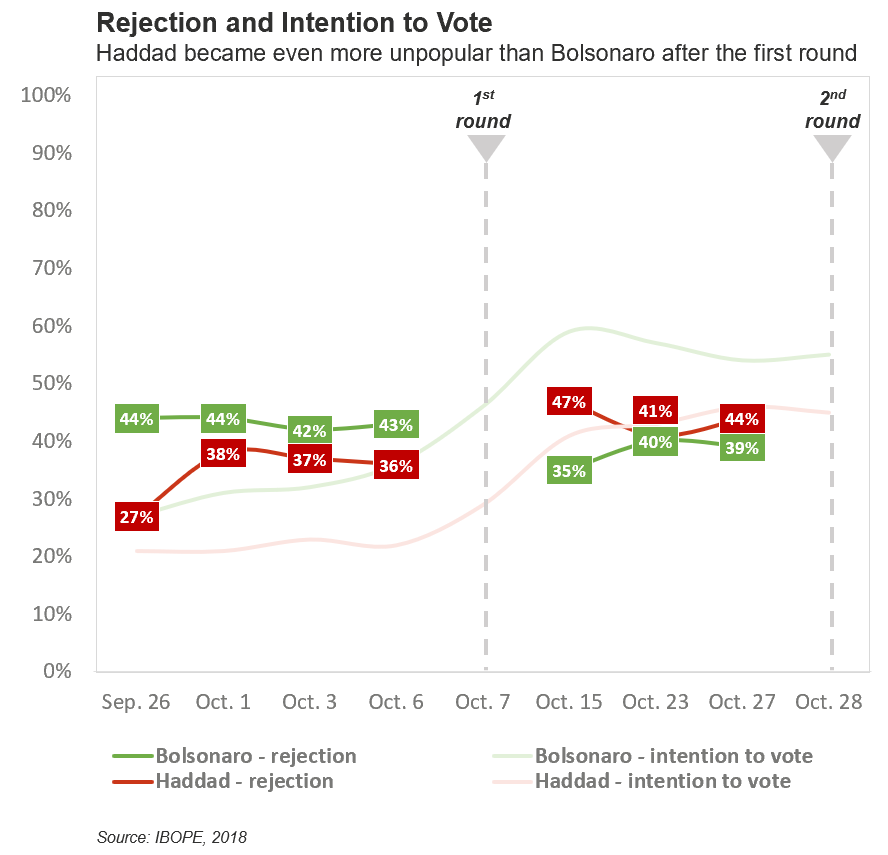

Early on, Bolsonaro was portrayed as the candidate incapable of building a popular voter coalition. However, it was ultimately Haddad—so intimately tied to Lula and the PT—who fell at the hands of voters who would vote for “anyone but him.”

Evangelical Churches

Since the fall of the military dictatorship in 1985, evangelicals have flexed political muscle through open support and endorsement of candidates. However, as their masses of followers swell—as of the 2010 census, evangelicals compose 22% of the population and are on pace to overtake Catholics by 2030—churches demonstrated an extraordinary ability to mobilize a captive, nationwide coalition of voters like never before. In an informal survey of members of Catalytic Communities‘* network of favela-based collaborators, respondents named evangelical churches as the number one political influence in their own communities during these elections—even ahead of WhatsApp and antipetismo.

Many of Brazil’s evangelical churches are not only houses of worship, but also hotbeds of conservative political activity. Prior to the first round of voting on October 7, a survey of Brazilian churchgoers revealed that 46% of Pentecostal evangelicals (a branch known for provocative and charismatic practices such as exorcisms and speaking in tongues) and 38% of non-Pentecostal evangelicals were aware of their pastor supporting a candidate, versus 29% of Catholic congregants. Nearly all respondents said that the endorsed candidate was Bolsonaro.

From unabashed opposition of LGBT rights and abortion to promising to “restore family values,” Bolsonaro’s social agenda dovetailed with that of many evangelicals. Evangelicals also proved to be staunch supporters of other elements of Bolsonaro’s ultra-conservative agenda not directly related to Christian theology, such as promises to cleanse Brazil’s streets of criminals.

Tying all the topics in this article together, perpetrators of fake news used religious faith to fan anti-Workers’ Party hysteria. Deliberately falsified rumors, such as the claim that Haddad’s government would teach sex at school and encourage homosexuality among schoolchildren, instigated many people, often with low digital literacy and only recently connected to smartphones where they are receiving such messages from friends and relatives, to vote against Haddad. While reporting on the influence of evangelicalism on this year’s election, BBC Brasil interviewed several evangelicals—all of whom quoted this rumor about Haddad. “The leftist class does not defend people from the traditional family,” claimed Celso Eranides, a Baptist pastor from São Paulo. “I don’t want my nine-year-old son to learn about sex at school.”

For many, the perception of shared religious values and fear of the alternative was decisive, even if many evangelicals are part of the working class that benefitted from the PT’s social programs. “Some evangelicals are being brainwashed by pastors who preach and spread hatred against parties of the Left,” remarked Emília de Souza, a community leader from Horto. “They’re able to erase people’s memories of the rights and advancements [achieved under the PT].”