For the original article in Portuguese published by the Institute of Alternative Policies for the Southern Cone (PACS) on Medium, click here. Reporting by Gizele Martins and Jessica Santos in partnership with the Brazilian Fund for Human Rights. This is the second article in a five-part series.

Janaína Mattos Alves, 35, saw her world crumble on the night of June 30, 2016. She was at home when the news arrived that her son Jhonata Dalber, 16, had been shot. “His friend arrived at my door desperately screaming, ‘They shot Dalber!’ I never thought that it would be the shot that killed my son. I thought that it was in the leg or arm, or a bullet scrape—that he would go to the hospital but survive,” Alves recalls. Jhonata had left his house in Usina (in Tijuca, in Rio’s North Zone) at his mother’s request to fetch bags of popcorn at a relative’s house that she had planned to bring to her younger child’s school celebration the following day. When she found out what happened, Alves went to the location where the action took place, but her son wasn’t there anymore. “I got to São Miguel (one of the main streets in Tijuca) by motorcycle and asked the police, ‘Where is my son?’ Until then, I didn’t know that they had removed the body. They laughed and mocked me,” she decries.

At the Andaraí Hospital, a group of Jhonata’s relatives and friends anxiously awaited news, which was the worst possible: he was already dead. The case was widely publicized in the mainstream media. The Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) Coordination Office published a note stating that following a confrontation with police officers, one man had been shot and hospitalized and the others had managed to flee. Alves recounts that after the murder, she did not have access to any information about what happened and the version of the facts that she knew—that he had been shot in a shootout—changed when the case was reported and reached the Public Prosecutor’s Office. “I didn’t know anything about my son’s case until it arrived at the Public Prosecutor’s Office, in the prosecutor’s hand. I discovered that the police shot him point-blank. They put a gun to my son’s head, burning an imprint of the gun in his head. Until then, we had thought that it was a rifle shot—but it was a .40 pistol shot and the autopsy report showed all of this.”

Lives Interrupted

Jhonata was in his first year of high school and had many friends and a girlfriend. He was excited to start computer and English courses at Saens Peña Square in Tijuca, scheduled to begin on the 14th of the month following his death. Like many youth his age, he planned to enter the job market, gain financial independence, and help his family. “He was eager to start working and helping me—he was a very helpful boy. I have always taught my children right and wrong. His dreams—and my own—were interrupted,” Janaína Alves laments.

The pain of losing a child is irreparable for any mother. When this death results from state violence, the process for those who survive the victim is much more complex. Alves says that in addition to dealing with her own mourning, she needs to stay strong to help her three young children—6, 9, and 11 years old, respectively—to overcome the trauma, in addition to the whole process of fighting for justice and defending the memory of her son. “The pain is doubled because it’s the pain of his absence and my children’s sadness. I try to stay strong to not show my grief.”

Olivia Morgado Françozo, a psychologist and psychoanalyst from the Nucleus of Psychosocial Support for Those Affected by State Violence (NAPAVE), explains that the majority of victims of “act of resistance” cases are black youth. Those who resist are the women who survive them and seek networks of support. For Françozo, losing a family member to murder affects everyone and often gives rise to feelings of self-blame. “They [the mothers] wonder where they went wrong because they can’t handle it and many of their sorrows are silenced. We believe very much in therapeutic group work, making them understand that this is a [de facto] government policy and not an isolated case. It’s a process of absolving guilt,” she says.

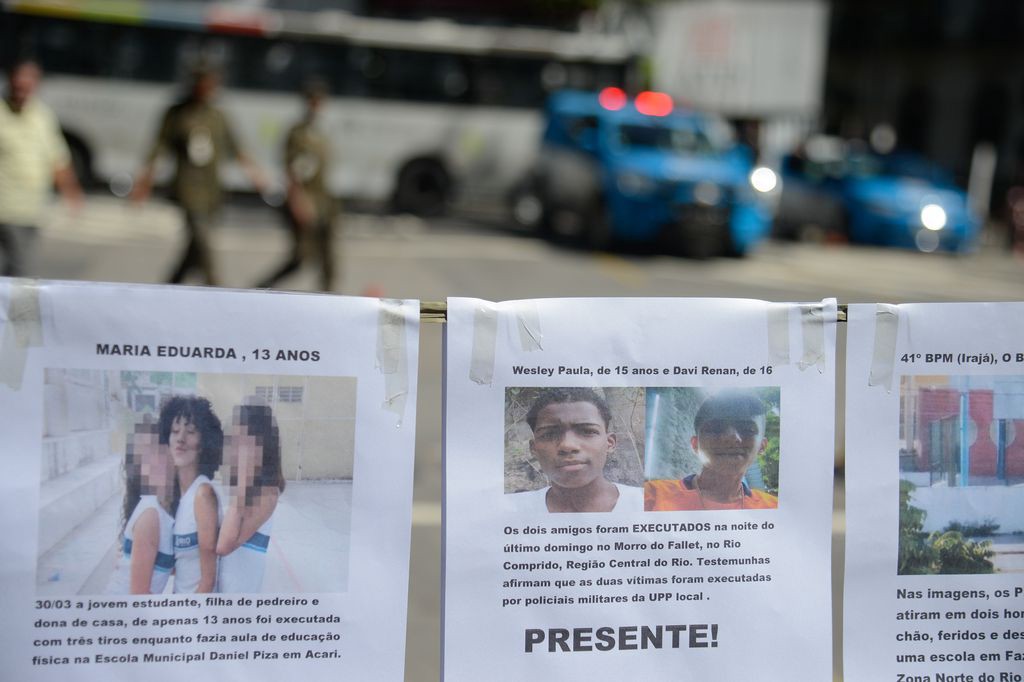

According to Françozo, recognition of the government’s responsibility is important in order to transfer blame from the mother and the family. “In their daily struggles, they are given spaces in newspapers to tell their version of the story, which is very important. On the other hand, the official accounts are rife with racism and the criminalization of poverty. Institutional racism and the government’s non-accountability are very heavy burdens for them to carry. They take responsibility for something that is not their fault. Family members’ effort to make those killed known—”Our Dead Have a Voice”—is a collective struggle.”

‘Our Dead Have a Voice’

While we were finishing this article, Rio de Janeiro’s movement of mothers and families of victims of state violence lost another warrior—a victim of pain, racism, and impunity. She shares a name with our interviewee for this article, Janaína. On November 6, 2018, Janaína Soares of the Mothers of Manguinhos movement died after seven cardiac arrests. Soares, who had lost her husband in a robbery in 2015, saw her son die at the hands of police in the favela where she lived. Soares was one of the women who relentlessly sought to stand up in pursuit of memory, justice, and a response from the government to the murder of her son Christian—who was only 13 years old at the time.

Each day, there are more and more mothers, fathers, and family members of victims of state violence—which means that each day, there are more women suffering from the pain of losing a child. This gives rise to women who end up devoting their lives and dedicating themselves exclusively to this struggle. Psychic reparations is among the causes for which they advocate.

They do all of this without any support from the government. “If the government had helped my family, financially and psychologically, I wouldn’t have had to go through some of these difficulties following my son’s death. My family became completely dysfunctional,” says Soares. Aside from facing financial troubles due to being unable to work, Soares deals with the traumatization of her younger children, who were failing at school after the tragedy.

According to Françozo, the psychologist, the loss of a loved one to state violence “has a huge impact on [families’] lives. It’s necessary to know what to do going forward—how they can receive support from public services and from networks of families and mothers. Here in Rio, there has been a lot of discussion about how to move forward in the wake of trauma—[acts] of violence that will forever shape their lives. They have ended up creating their own support networks since the government has not guaranteed care for these mothers and family members,” she comments.

The Network of Mothers Against Violence has been an important source of strength. For Janaína Alves, her family’s support and her activism work were fundamental to muster the strength to carry on after Jhonata’s death. “I met the mothers right after my son’s death. They organized a breakfast gathering for me, which they called the ‘Breakfast of the Strong.’ There, they told me a little about each of their stories and struggles following their children’s deaths and showed me that I had to fight, that I was my son’s voice at that moment. They showed me that I couldn’t give up—that if I didn’t fight, the guilty would not pay [for their crime] and there would be no justice,” she passionately recalls.

Self-created supportive spaces such as these enable the families to overcome the fear of speaking up about their cases, in addition to providing opportunities to get to know other mothers and their stories in the pursuit of justice.

Impunity

As in the case of Janaína Alves, more women and family members now mourn the deaths of their sons, husbands, and relatives in Rio de Janeiro—a state that has been under military intervention since February 16, 2018. According to data from the Institute of Public Security, between January and September 2018, there were 1,181 act of resistance cases, of which 416 occurred in the Baixada Fluminense; 147 in the interior of the state of Rio, 198 in Greater Niterói (a nearby city); and 420 in the capital city. Of this total, 80% of all cases occurred in the capital and in the Baixada Fluminense, meaning that act of resistance cases occur more frequently in Rio’s favelas and peripheries. These statistics are considered the worst in Rio’s history with regard to the increase in the number of act of resistance cases.

Beyond the historic increase, military officials have already made several declarations asserting that it is necessary to change the term “act of resistance” to “legitimate self-defense.” Military administrators thus aim to legitimize the massacre, genocide, and militarization of black lives and the lives of residents of favelas and peripheries.

The increase in the number of cases makes us ask why this extermination policy remains in force in the face of countless national and international denunciations, confirming that Brazil is a country that violates rights and that this policy is a part of institutional racism. Furthermore, many cases don’t receive coverage in the mainstream media and end up not going to trial because the Brazilian government itself creates a climate of fear, such that many family members don’t even have the chance to think about making a denunciation or going to public agencies to seek legal support.

The ways by which the government produces this climate of fear and criminalizes poverty are clear upon analyzing the statements made by public authorities and military generals. For example, this can be seen when the officials behind the military intervention in Rio affirm that this year was a success, claiming that cargo theft has declined. This has been a year of sadness, outrage, and great pain for residents of favelas and peripheries and for the families of these victims—lives massacred in the name of a “war on organized crime.” In other words, this is a top-down policy of extermination at the behest government authorities and the Armed Forces.

The failure to bring the majority of these cases to trial is another point that calls attention, demonstrating how authorities work together to ensure that the police and army feel comfortable continuing to commit such abuses and massacres. At this moment of military intervention in Rio de Janeiro, it is not clear who is responsible for responding to these cases, since the operations that are taking place in Rio’s favelas and peripheries are carried out by both the Civil and Military Police forces. This allows police to keep their responsibility for violations committed in impoverished places “under wraps,” as seen in the case of the massacre in Salgueiro—a favela located in São Gonçalo, in Greater Rio. The case was archived due to doubts surrounding authorship of the crimes committed, meaning that the three parties involved (both the Civil and Military Police, as well as the Armed Forces) protected themselves by acting together as they have not been held responsible for their actions.

It’s clear that this policy of extermination carried out by the government is a well-established practice in Rio de Janeiro. Over the past ten years, favelas and peripheries have suffered from the increase of the military power in favelas, the entrance of Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), as well as the entrance of the army. Throughout this period, governing administrations have affirmed that favela residents are public enemies that should be fought, as Sérgio Cabral said when stating that “women from favelas are factories for criminals.” Over the past ten years, 16,000 people have been killed—victims of police actions in Rio’s favelas and peripheries. According to a survey carried out by the Grita Baixada Forum and the Human Rights Center of Nova Iguaçu as part of their Strategic Litigation project and based on data from the Civil Police, there were 2,046 act of resistance cases in the Baixada Fluminense between 2010 and 2015. The 15th Battalion of the Rio de Janeiro Military Police of Duque de Caxias was the most heavily involved.

The new administration has also expressed that military practices will be increasingly present in Rio’s impoverished neighborhoods. “The correct thing to do is to kill criminals carrying guns. The police will look at their little heads and… fire!” said Rio de Janeiro’s governor-elect Wilson Witzel, who will run the state for the next four years. This statement from the new governor illustrates the rise of genocidal practices in Rio’s favelas and peripheries. This is a population that is considered the enemy of the city and of the State—and this governor wants to gun down the “little heads” of black youth from favelas and peripheries [even young children may be found carrying guns as part of the lower echelons of drug trafficking in Rio].

Thus, we ask, to whom do we turn in the face of the increasing act of resistance cases, massacres, and operations—now carried out with armored helicopters and vehicles and war tanks? To whom do we appeal when the government itself is legitimizing the license to kill, when the judiciary is complicit in the government’s practices by failing to take these cases to trial, thus legitimizing impunity?

Reports, stories, and testimonies such as these have been denounced to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IAHCR) which visited Brazil, by movements of mothers and family members of victims of state violence, and by groups that take part in favela movements in Rio de Janeiro. At a press conference, the IAHCR stated that the Brazilian government should respond to the act of resistance cases, massacres, forced disappearances, and all of the rights violations committed by police forces and by the Brazilian Army in the favelas and peripheries of Rio de Janeiro.

This is the second article in a five-part series.