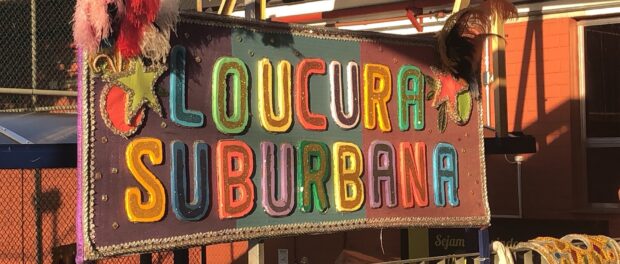

On February 19, the Suburban Madness Carnival group, or bloco, held an event at the SESC cultural center in Engenho de Dentro, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, to choose the group’s 2019 samba song. The bloco, which is hosted annually at the Nise da Silveira Municipal Institute (more commonly known as “Nise”), was founded in 2001 to offer patients at the psychiatric hospital a form of treatment and interaction that goes beyond the asylum model. It’s no coincidence that 2001 was the same year in which Brazil concretized the Psychiatric Reform movement by passing Law 10.216/2001.

The official parade takes place every year on the Thursday before Carnival. Thus, this year, the bloco will congregate at 4pm on February 28, at Rua Ramiro Magalhães 251 in Engenho de Dentro, with the parade beginning at 5pm. While many of the bloco’s participants are people who receive treatment or are employed by the Mental Health Network, all are invited. Indeed, Abel Luis, the bloco’s musical coordinator, emphasized that all rehearsals and workshops are open to the public.

The Importance of Using Carnival to Talk about Mental Health

To open the song-selecting event, Ariadne de Moura, Loucura Suburbana’s general coordinator, noted the importance of the bloco as a space of resistance and struggle in the anti-asylum movement. She contextualized her speech within larger concerns about potential setbacks in the area of mental health.

Recently, the Ministry of Health issued Technical Note 11/2019, calling for changes and new guidelines for the National Mental Health Policy and the National Drug Policy. The decree was met with pushback from several health sectors, including the Federal Psychology Council and the Federal Council of Physical and Occupational Therapy. A few days following the announcement, the Ministry of Health withdrew the decree.

Sidimar Marinho has been a member of the bloco’s team and served as its master of ceremonies since 2001, collaborating with flag-bearer Elisama Arnaud. A beneficiary of the Mental Health Network himself, he explains how the bloco and the many workshops it holds throughout the year can be quite beneficial for people in treatment: “Sometimes, a colleague shows up in the middle of a crisis and just coming to the bloco can help them feel better. After, they’re able to go home and be with family… We all help each other out and encourage our peers to participate.”

Marinho emphasizes the power of art and interconnection in helping psychiatric patients recuperate. The bloco gives an opportunity to participants to exercise their right to community and leisure as they dance and sing to the samba beats and even perform sambas that they themselves created at the Free Music Workshop.

The psychiatric institute that houses Loucura Suburbana is named after psychiatrist Nise da Silveira, who pioneered the use of artistic expression as a therapeutic practice. In 1946, Nise took the helm of the Occupational Therapy sector at the former National Psychiatric Center (previously the Engenho de Dentro Colony for Alienated Women, today the Nise da Silveira Municipal Institute), where she used painting and sculpture as means for accessing her patients’ unconscious minds. As creative production increased at the atelier, Silveira founded the Museum of Images of the Unconscious. She took an additional step towards deinstitutionalization when, in 1956, she founded Casa das Palmeiras for formerly institutionalized individuals, offering mental health activities outside of a formal psychiatric institution.

Selecting a Samba

The process of selecting a samba begins with a presentation of each song, first without music, and later accompanied by the percussion group “A Insandecida.” Jury members then meet to select three finalists—this year, due to the quality of the sambas, they chose four—and there is a final performance, after which one song emerges as the samba of the year.

This year, the jury consisted of eighteen members from different institutions, including other carnival blocos. Among those chosen to participate were Paulo Amarante, Débora Resende, Mestre Folia (who wrote “Tá Pirando, Pirado, Pirou”), and Tatiana dos Santos.

This year, the finalists were: “I am Suburban Madness,” by Elisama Arnaud and André Cabral; “Popular Patrimony,” by Michel Indiano; “From the Asylum to Nise da Silveira Park: Suburban Madness Parading through History,” by Eurípedes Júnior; and “Doctor, I Hear Voices,” by Angela Maria Soares de Carvalho and Paulo Fernando.

The night’s winner was “Doctor, I Hear Voices,” which was recognized for addressing the necessity of political resistance and alternative treatments to the asylum model. Check out the full lyrics below:

Doctor, I hear voices

Voices from beyond

Resisting is a must

No one let go of anyone’s hand!!Medicine over here

Workshop over there

In therapy, I come to find myself

And if I feel a pang of longing

I just want to love

Suburban Madness will passLoucura Suburbana

Once again

Suburban Madness is with you all

Crowdfunding Campaign

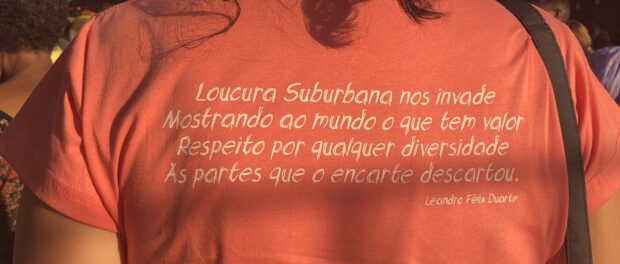

Despite the bloco’s celebratory and joyous spirit, organizing the parade is a constant struggle. The group lacks sufficient funding to create costumes, promotional T-shirts, and other materials, as well as for car rental, repairs to percussion instruments, and other necessities. For these reasons, the bloco has started a crowdfunding campaign, so that fans can lend support and help make the parade possible this year.

To help Loucura Suburbana click here.