In 1991, then-president Fernando Collor de Mello sent Brazil’s federal Congress a proposition of what would later become the country’s national waste management policy. The idea was to present that policy at the 1992 United Nations Conference on the Environment and Development (UNCED, also known as the Earth Summit) and show the world that Brazil was finally giving due attention to the environment with regard to the waste produced in its cities.

Previously, each municipality had been tasked with formulating and implementing its own waste management plan. There was no facilitation of public financing for the sector, which at the time merely consisted of collecting garbage from urban areas and disposing of it in landfills located in urban peripheries. All types of environmental contamination were to be found at these disposal sites. They were breeding grounds for disease vectors that are harmful to human health. It’s no accident that diseases such as dengue, yellow fever, and diphtheria became endemic in the mid-1980s, initially in large cities.

In the degrading and contaminated setting of landfills, among garbage and vultures, there were people who sorted waste—separating materials that could be sold as scraps, and, later on, to the recycling industry. As such, these previously invisible workers stopped focusing on garbage collection and turned their attention toward recyclable materials—forms of waste that could potentially be reintroduced into the production process and are thus in demand in the recycling industry.

These people, who have worked in Brazilian landfills since the end of the 19th century, call themselves catadores—a word originating in the rural settings from which they came. When they migrated from rural areas to cities and couldn’t achieve the minimum necessary conditions to survive in a dignified way, they ended up in landfills to see what they could find at these sites. As such, the environmental contamination problem was compounded by the social issue of people living at these sites and surviving on the waste that is dumped in official and clandestine landfills in Brazilian cities every day.

Resulting from intense debates across diverse sectors of society, the National Solid Waste Policy (PNRS) was finally implemented by the Brazilian government on August 2, 2010, in an effort to regulate the activities of the solid waste sector in Brazil. The policy provides for cooperation among the stakeholders involved—the three levels of government (federal, state, municipal), the recycling and packaging industries, society and the recyclable materials collectors—in order to fulfill its objectives and recommendations.

In summary, the PNRS proposes:

- The eradication of landfills;

- The incentivization of waste sorting;

- The participation of recyclable materials collectors in the recycling process;

- Support for strategies that promote recycling; and

- Final waste disposal via sanitary landfills and/or incineration, provided there is an energetic return.

In this sense, the discussion agenda on the implementation of the PNRS came to include considerations such as reverse logistics (that is, forms of collecting and re-inserting solid waste into the business sector for reuse or adequate disposal), sectoral agreements (contracts between public authorities and manufacturers that determine shared responsibility of product life cycles), the payment of recyclable materials collectors for environmental services provided to society, the construction of sanitary landfills, and separation of waste for recycling.

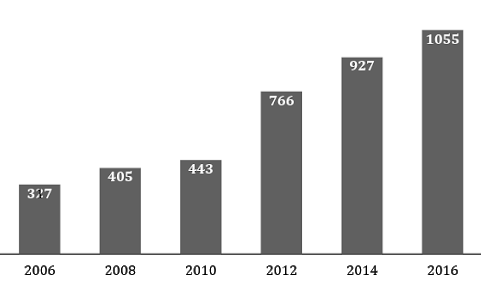

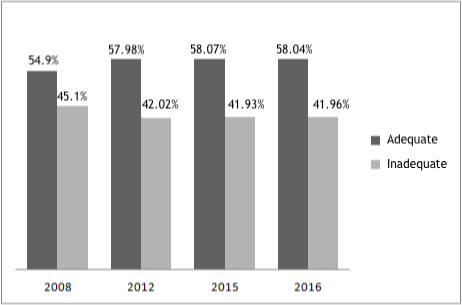

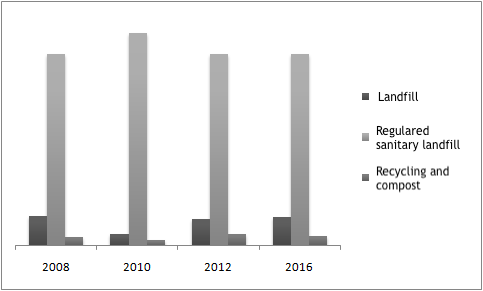

The following tables represent the period before and after the emergence of the PNRS in 2010:

Final Disposal of Solid Waste:

Location of Final Disposal of Waste:

Number of Brazilian Cities with Recycling Programs:

Cities had four years to meet the PNRS recommendations. Therefore, starting in August 2014, the expectation was that cities eradicate all landfills (whether official or clandestine) and meet all legal recommendations and that recyclable materials collectors no longer roam the streets of Brazilian cities nor landfills, working in unsanitary conditions. Moreover, the policy aimed to address the low wages earned by recyclable materials collectors, who typically make less than Brazil’s monthly minimum wage.

On January 16, 2019, we visited the Association of Recyclable Materials Collectors of the closed Jardim Gramacho Metropolitan Landfill (ACAMJG) located in Duque de Caxias, in the Baixada Fluminense. The association gained international recognition due to the documentary Waste Land, which was nominated for an Oscar in 2011. Through continued contact with the association, we identified aspects of the National Solid Waste Policy that should be fulfilled by their municipal government, of Duque de Caxias, but that in practice, are not.

Caring for the Environment

The PNRS is innovative in that it is a policy that links socioeconomic issues to environmental issues. The reality of waste management in the city leaves much to desire in both respects. The river that flows by the Gramacho association is heavily silted due to the clandestine disposal of civil construction debris and slaughterhouse waste. Standing close to the river, you smell the stench of waste—a stench stemming from the lack of care and respect for either people or the environment.

Reverse Logistics

One of the main aspects of the PNRS is the elaboration of a reverse logistics plan that includes the packaging industry. As such, in 2015, an agreement was signed such that the sector would support municipal initiatives that provide for cost-sharing between companies and municipal governments for the management of discarded packaging waste. In this way, the agreement would fulfill one of the objectives of the PNRS: shared responsibility for waste management between municipal agencies and the private sector.

Furthermore, with reverse logistics, there is also an ethical obligation to care for the environment: whoever produced the waste must assume responsibility for its proper disposal.

The waste triage warehouses belonging to the Association of Waste Pickers of the Jardim Gramacho Metropolitan Landfill bring to mind the book No Logo by Naomi Klein. In the book, Klein draws connections between major industry brands and the various economic, social, and environmental infractions caused by these industries in Asian countries.

As such, the waste points to certain brands that manufacture important industrial products. Passed over three years ago, the sectorial agreement between municipalities, state governments, the Ministry of the Environment, the packaging industry, the recycling industry, and associations of recyclable materials collectors still only exists on paper—the agreement was properly formalized, but is nonfunctional in practice.

Self-Managed Entities

According to the PNRS, associations of recyclable materials collectors must be self-managed—that is, they should take responsibility for every aspect of their management. The use of individual protection gear that is not adequate for the activities carried out by recyclable materials collectors, poor workplace conditions (including the formation of extremely high-temperature microclimates), and the absence of machines and equipment that could facilitate their jobs are constant challenges. There is also the need to reinforce the importance of safety culture in the workplace together with recyclable materials collectors.

Recycling: Income and Employment Generation

In Brazil, over 90% of the materials that are eventually recycled are collected by more than one million recyclable materials collectors. One of the pillars of the PNRS is the streamlining of recycling, which serves to generate employment and income for recyclable materials collectors. Recycling is an industrial sector that grows 12% per year on average. This sector’s market takes the shape of an oligopsony—that is, a few large buyers and many small sellers.

Therefore, when industries join the ranks of those pushing for municipalities to front the costs of recycling on their own, it raises the question: might this be a veiled way of socializing the private costs of the recycling industry, if not a form of economic environmentalism?

New Legislation and Perspectives

In 2019, the new administrations of the executive branch of the Brazilian government (the president and state governors) and members of Congress took office. In its ministerial reform, the new federal administration first opted to extinguish the Ministry of Environment, merging it with the Ministry of Agriculture. The Ministry of the Environment was not ultimately dissolved. However, many of its duties were distributed to other ministries.

It is not clear what the administration intends to do with regard to the waste management sector. Nonetheless, given the budget cuts impacting various social policies, of which recyclable materials collectors are direct beneficiaries, the prospects are not encouraging.

Fábio Fonseca Figueiredo has a Ph.D. in Human Geography from the University of Barcelona, Spain. He is a professor in the Department of Public Policy and in the Graduate Program in Urban and Regional Studies at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) and is a member of the Social Economy of the Environment and Environmental Policy (SEMAPA) research group at UFRN.

Valeria Pereira Bastos has a Ph.D. in Social Service from the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC–Rio). She is a professor in the Department of Social Work at PUC–Rio and is a member of the Urban and Socio-Environmental Studies Laboratory (LEUS).