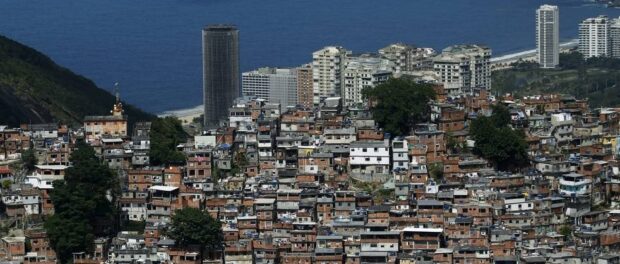

Time goes by, and those in Rio de Janeiro’s government continue to insist upon announcing grand schemes for the favelas. This time it’s a “grand boulevard” in the South Zone favela of Rocinha, involving R$1.5 billion (US$363 million) in investments, according to Governor Wilson Witzel.

Favela residents’ lives are spent amid the absence of basic sanitation, the violence of incomplete citizenship, the precariousness of housing, the risk of landslides, and difficult mobility. Nonetheless, governments come and go, and favela residents continue to be treated like guinea pigs in an urban laboratory. Generation after generation is ignored as an indelible part of society. Despite favela residents’ historic fight for affirmation, all we have to offer them is massive works and contractors. Even as black and brown youth continue to define Brazilian cultural identity with their faces and souls, all we offer them are experimental improvements created by “inspired” politicians.

Favela-Bairro, Morar Carioca, the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), the Growth Acceleration Program in favelas (PAC das Favelas), Urbanistic and Social Orientation Posts (POUSOs), land tenure—this is the terminology we use to describe how we’ll improve these sub-citizens’ lives. If they suffer or die, they are just casualties in the great trial-and-error experiment that it is to govern Rio de Janeiro.

Since Rio’s mayor seems to be stuck in a trance, the governor has assumed some essential municipal administrative functions. He has already tasked himself with the Sambadrome and with urban order. The governor’s recent announcement of a beautification-driven urban intervention in Rocinha came without explanation of what data he holds, what technical evidence exists, what urbanization project would be implemented, or how the process of community consultation was carried out. As such, he is repeating the errors of his predecessors.

Rocinha is the only favela with a master plan for urban and environmental development elaborated through a participatory process and contracted by the state government. Yet the plan has always been ignored by the mayor’s office—which is constitutionally responsible for land use management—and abandoned by all when the cash-cow panacea that was the PAC arrived, and we could buy cable cars like rice at the supermarket. Who can buy food today? But that’s another matter, isn’t it?

The only approach to informal settlements that has never been attempted since the democratization of the country is to institutionalize community self-management. We never established participatory budgeting in favelas. We never gave legal property rights for shared common land (which would resolve the issue of militia oppression in Rio das Pedras, for instance). We never instituted technical assistance, as laid out in Law 11.888, and never did we allocate the more than R$400 billion spent (US$97 billion) on the Minha Casa Minha Vida program’s segment intended for community development. Our very few inclusive experiments have, indeed, been forgotten with time.

If the urgency to improve living conditions is legitimate, our haste has resulted in uninformed and sloppily cobbled-together work. Following through with plans, monitoring results, maintaining transparent processes, and allowing populations to be the masters of their own transformations are the most effective and just means for undertaking major policy.

Everything has always been and continues to be decided by the few, and for the few, as we dole out construction contracts to an even more select few. The Right and the Left have acted exactly the same in their laboratory tests. We have never tried a different way because that would require time and patience, change doesn’t happen in four years, we must admit our ignorance, compile technical information, and because political reputations are precious, for our lives are long—whereas the guinea pigs, well, they don’t last quite so long.

Architect and urbanist, Washington Fajardo was Special Advisor on urban issues under Mayor Eduardo Paes. He is also the former president of the Rio World Heritage Institute, a consultant on Rio de Janeiro’s Architecture and Urbanism Council (CAU-RJ), and creator of the architecture firm Desenho Brasileiro. He is a Loeb Fellow 19 at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and DRCLAS Visiting Researcher.