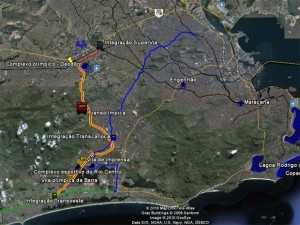

Connecting Barra da Tijuca and the Olympic Park with the International Airport, the Transcarioca highway and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) route is the most visible transport infrastructure work the city of Rio is undertaking in preparation for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics. Officials estimate that the 39km expressway and its 45 bus stations will serve 400,000 passengers per day and cut journey time between Barra and the airport by 60%. However, of the three BRT transport projects under construction – the others being the TransOeste linking far West Zone neighborhood of Santa Cruz with Barra and the TransOlímpica between Barra and Deodoro where Olympic events will also take place – the Transcarioca is responsible for the most evictions with an estimate last year that 3630 families would be displaced.

Irregularities pervade the execution of works and evictions along the Transcarioca route, which passes through major centers in Rio’s populous North Zone. In 2011, the Largo do Campinho community was removed with reports of sudden arrival of demolition teams without prior notification, intimidating and threatening tactics and unfair or no compensation. Currently, works are taking place in the historic neighborhood Penha where similar illegalities occur.

When lifelong Penha resident Marcia Cristina Santos Costa, 49, went to the official presentation of the Transcarioca project to the local community in June 2010, she was told that her house would not be removed. Repeated assurance was given that the family home she built up thirty years ago behind her husband’s family’s property wouldn’t need to be cleared, but that she should present paperwork and and resolve any irregularities to ensure it would remain. Yet despite these assurances, her compliance with requests and the house not being within the 12 meter strip required for the works, officials arrived at her home on Friday October 5th with an eviction order giving the family a week to vacate the property without any alternative accommodation, social rent or compensation since this is being held up by the courts because of a family dispute. She frantically arranged places for each family member and possessions to stay and the following week their house was demolished.

When lifelong Penha resident Marcia Cristina Santos Costa, 49, went to the official presentation of the Transcarioca project to the local community in June 2010, she was told that her house would not be removed. Repeated assurance was given that the family home she built up thirty years ago behind her husband’s family’s property wouldn’t need to be cleared, but that she should present paperwork and and resolve any irregularities to ensure it would remain. Yet despite these assurances, her compliance with requests and the house not being within the 12 meter strip required for the works, officials arrived at her home on Friday October 5th with an eviction order giving the family a week to vacate the property without any alternative accommodation, social rent or compensation since this is being held up by the courts because of a family dispute. She frantically arranged places for each family member and possessions to stay and the following week their house was demolished.

Describing the process standing in the rubble of her home, Marcia says: “You need a period of time to organize yourself. They didn’t give me this period. The city representatives came with a lot of sledgehammers and without the least bit of sensitivity. They think it’s not a problem psychologically but it is. How can you dismantle people’s lives, remove them from their homes without them knowing where to go?”

She says “I did everything the city authorities requested. I arranged for an architect and engineer to come to prove that it didn’t need to come down. The authorities said that just because your neighbor’s house is coming down doesn’t mean yours will. The whole time a representative was saying ‘the city government doesn’t want to put anyone out on the street.’ She also said that everyone that has to leave will receive money to be able to arrange something else. This didn’t happen in my case.”

She says “I did everything the city authorities requested. I arranged for an architect and engineer to come to prove that it didn’t need to come down. The authorities said that just because your neighbor’s house is coming down doesn’t mean yours will. The whole time a representative was saying ‘the city government doesn’t want to put anyone out on the street.’ She also said that everyone that has to leave will receive money to be able to arrange something else. This didn’t happen in my case.”

With her husband and two sons all staying with separate friends or relatives and no news of compensation, Marcia speaks of how she’s fallen apart since the eviction and spends sleepless nights worrying about what to do. She remains indignant about the way she’s been treated in the way the works are going ahead, saying, “What’s happening with the Transcarioca is that city authorities can do whatever they want for the ‘greater good of the community and society’ but it’s a lie that they don’t put anyone out on the street. They put me out on the street.”

The view that the authorities are acting without regulation or restriction is echoed in technical reports evaluating the Transcarioca works, which are being carried out by a consortium of private companies. Court of Auditors’ reports from last year show that work often starts without the finalized plans or that the Executive Plan is altered in the course of the works. June this year civil society organizations filed a lawsuit requesting the cancellation of the works’ environmental license and suspension of finance for the Transcarioca, alleging the project is full of irregularities and omits the real social and environmental impact. The lawsuit highlighted changes in the plans that result in more, not fewer, evictions, than planned. One specialist following the Transcarioca works calls it “a total mess. The objective isn’t necessarily to remove more houses but they do things freely without having to give an explanation to society or specialist bodies.”

The view that the authorities are acting without regulation or restriction is echoed in technical reports evaluating the Transcarioca works, which are being carried out by a consortium of private companies. Court of Auditors’ reports from last year show that work often starts without the finalized plans or that the Executive Plan is altered in the course of the works. June this year civil society organizations filed a lawsuit requesting the cancellation of the works’ environmental license and suspension of finance for the Transcarioca, alleging the project is full of irregularities and omits the real social and environmental impact. The lawsuit highlighted changes in the plans that result in more, not fewer, evictions, than planned. One specialist following the Transcarioca works calls it “a total mess. The objective isn’t necessarily to remove more houses but they do things freely without having to give an explanation to society or specialist bodies.”