On July 18, a protest against religious intolerance took place in Duque de Caxias, in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, at the former site of the terreiro (outdoor place of worship for Afro-Brazilian religions) of Joãozinho da Gomeia, babalorixá (high priest) of the Candomblé religion. The demonstration was organized because the mayor of the city, Washington Reis, announced that a daycare center would be constructed on the site, abandoning the current recovery process of the historical memory and religious significance of the place. Participants in the demonstration called for the space to be preserved as a heritage site. Currently, the site is considered unsanitary and is abandoned.

On July 27, almost ten days later, the demands made by the black movement and by religious movements were met by the Duque de Caxias city government: the site will be preserved, and the sacred memory of the land will be maintained. The municipal government resolved to build the new school unit in a different location, fence off the land, and clean up the site.

Understand the Case and Its Importance to Afro-Brazilian Culture

Who was João da Gomeia?

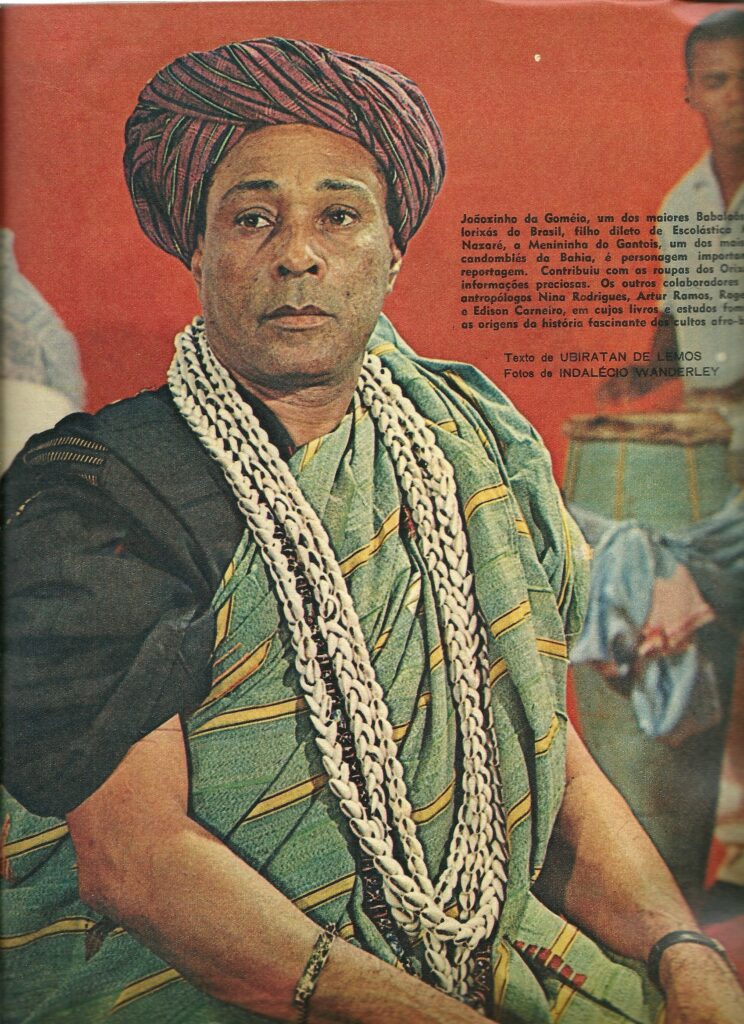

Considered the most famous Brazilian babalorixá, João Alves Torres Filho, from the state of Bahia, better known as João da Gomeia, was an important pai de santo (male priest) in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1946, he moved to Rio de Janeiro, establishing his terreiro in Duque de Caxias, where he attended to politicians and artists. Rumor has it that former Brazilian presidents Getúlio Vargas and Juscelino Kubitschek visited him at his terreiro. His bibliography is the subject of two published books, one play, academic studies, and, more recently, a parade theme in Rio’s carnival. In 2020, the samba school Grande Rio, which is located in the same municipality as the terreiro, took the story to Rio’s Sambadrome. The tribute considered the artistic soul and religious life of the pai de santo.

Considered the most famous Brazilian babalorixá, João Alves Torres Filho, from the state of Bahia, better known as João da Gomeia, was an important pai de santo (male priest) in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1946, he moved to Rio de Janeiro, establishing his terreiro in Duque de Caxias, where he attended to politicians and artists. Rumor has it that former Brazilian presidents Getúlio Vargas and Juscelino Kubitschek visited him at his terreiro. His bibliography is the subject of two published books, one play, academic studies, and, more recently, a parade theme in Rio’s carnival. In 2020, the samba school Grande Rio, which is located in the same municipality as the terreiro, took the story to Rio’s Sambadrome. The tribute considered the artistic soul and religious life of the pai de santo.

In addition to his renowned and respected spirituality, the pai de santo was also an artist who brought the terreiro dances to the stages of theaters in Salvador and Rio de Janeiro. The religious community did not receive these (public) performances well, but the babalorixá, with his striking and irreverent personality, kept his art alive despite the criticism.

Currently, there is a committee dedicated to keeping the memory and work of the babalorixá alive. The Gomeia Committee is led by Pai João’s filha de santo (a female religious pupil, spiritual daughter), Seci Caxi (sacred name given to Sandra Seci Reis), and since 2015 they have planned to build the Joãozinho da Gomeia Memorial. The Rio de Janeiro State Institute of Cultural Heritage (INEPAC) also initiated a process to establish the area as a protected public landmark, which is still underway. “I’m not against it. No one here is against the construction of a daycare. But this is a sacred site and we must respect Pai João and the importance of his name within Afro-Brazilian culture,” said Seci de Caxi during the July 18 protest.

Pai João’s terreiro unquestionably made its mark on Brazilian history. But more deeply still, it marked the lives of many residents of the Baixada Fluminense, such as that of journalist Sílvia Mendonça, Ekedi (spiritual role in the Candomblé religion), a resident of Duque de Caxias and activist in the black movement. “I was born nearby, and my family used to come to the parties. I’m the youngest, but my oldest brother would be 97 years old if he were still alive. My father was born in 1900. Everyone knew Pai João’s stories around here, but no one knew him as Joãozinho da Gomeia. He was Pai João. And what would be the importance of building [the daycare] here? It’s not only about preserving his memory, that wasn’t the only thing he wanted. He wanted to empower the population. The black population especially.”

The importance of sacred terreiro sites

The sites where terreiros are built are important beyond offering a physical gathering space for followers of the same faith. The sites are made holy before the first foundations are even laid. The consecrations or settlements, as they’re known, are conducted to sanctify the area and spiritually protect its visitors, in accordance with the rites of this religion.

These sacred rituals and all of the importance that Joãozinho da Gomeia had and still has today were not taken into account during the decision by local authorities to establish a social services building with no relation to the memory of the place. The history of Brazil and its peripheries has always been retold through the biased lens of European colonizers, and these narratives have been contested by the black movement for some years now.

Religious intolerance and racism

Religious intolerance occurs when there is prejudice against the sacred rites of a certain religion. A number of religions are attacked due to their particularities and rituals. However, religions of African origin are the ones that suffer the most incisive and recurring attacks in Brazil. And why are these attacks so specific? Because along with intolerance comes religious racism. The data don’t lie: religious persecution appears in the religious intolerance report produced by the Center for Articulation of Marginalized Peoples (CEAP) conducted by Dr. Babalawo Ivanir do Santos. The findings indicate that between April 2012 and August 2015, 71% of religious attacks in Brazil were against Afro-Brazilian religions, while Brazilian evangelicals were the second-most attacked religion. However, they accounted for only 8% of cases. By September 2019, 200 cases of religious racism had been registered in the state of Rio de Janeiro. 35% of them occurred in the Baixada Fluminense. These numbers, however, might be even higher, since these incidents tend to be underreported.

Representatives of the religion say that positions such as those taken by the Duque de Caxias city government must be questioned whenever necessary, because a sacred site is important, not only for preservation of spiritual memory but also for the legacy of Afro-Brazilian culture. Religious leaders also stress that the struggle contributes to efforts against the erasure of history that is relevant to the black community and to Brazil. The city’s decision was the first step in this victory. Now, the next step is to ensure that the projects envisioned by the religious movements are carried out, namely: the creation of a cultural space with activities centered around black culture and a memorial to the history of João da Gomeia. Initiatives such as these are a way not only to pay tribute to the legacy of the babalorixá, but also as an important political statement in terms of racial issues.

For this reason, affirmative action policies are increasingly and urgently needed in the fight against racism, in all spheres. The debate about where and how racist structures interfere in the lives of the black population contributes to the study and the expansion of truly democratic public policies. Symbolic and concrete attacks on religions of African origin undermine the free exercise of faith in a pluralistic and, at the same time, individual manner. This is a political and fundamental debate, since keeping the plurality of religious memory alive is the duty of a country that declares itself secular. Preserving black memory and history is not only a question of justice, but also a question of democracy.

Carla Souza is an educator by training and an early childhood teacher who is passionate about her profession. Raised in Rocinha, she understands her existence as a black, favela woman as a focal point for struggle and resistance in the world.