This is the second article in a five-part series, published in Portuguese by favela-based online magazine Favela em Pauta and titled “Brazils: Stories of the Periphery in the Pandemic.” Each essay comes from a different region of Brazil; this one from the nation’s North. For the original article by Ariel Bentes click here. It is also our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on favelas.

What stories do the peripheries tell about the pandemic and inequality? This is the question we wanted to answer when we invited five journalists—residents of peripheries in each of Brazil’s five regions—to participate in this project. The idea emerged from the Coronavirus in the Peripheries Map, an initiative of the Marielle Franco Institute which registered more than 540 collectives that act on the frontlines against Covid-19, in favelas and peripheries across the country. Engaging with the data and stories of these collectives and what they have witnessed, the visions of these five journalists show that it is possible to understand the simultaneous similarities and differences of living in the different Brazils that make up Brazil.

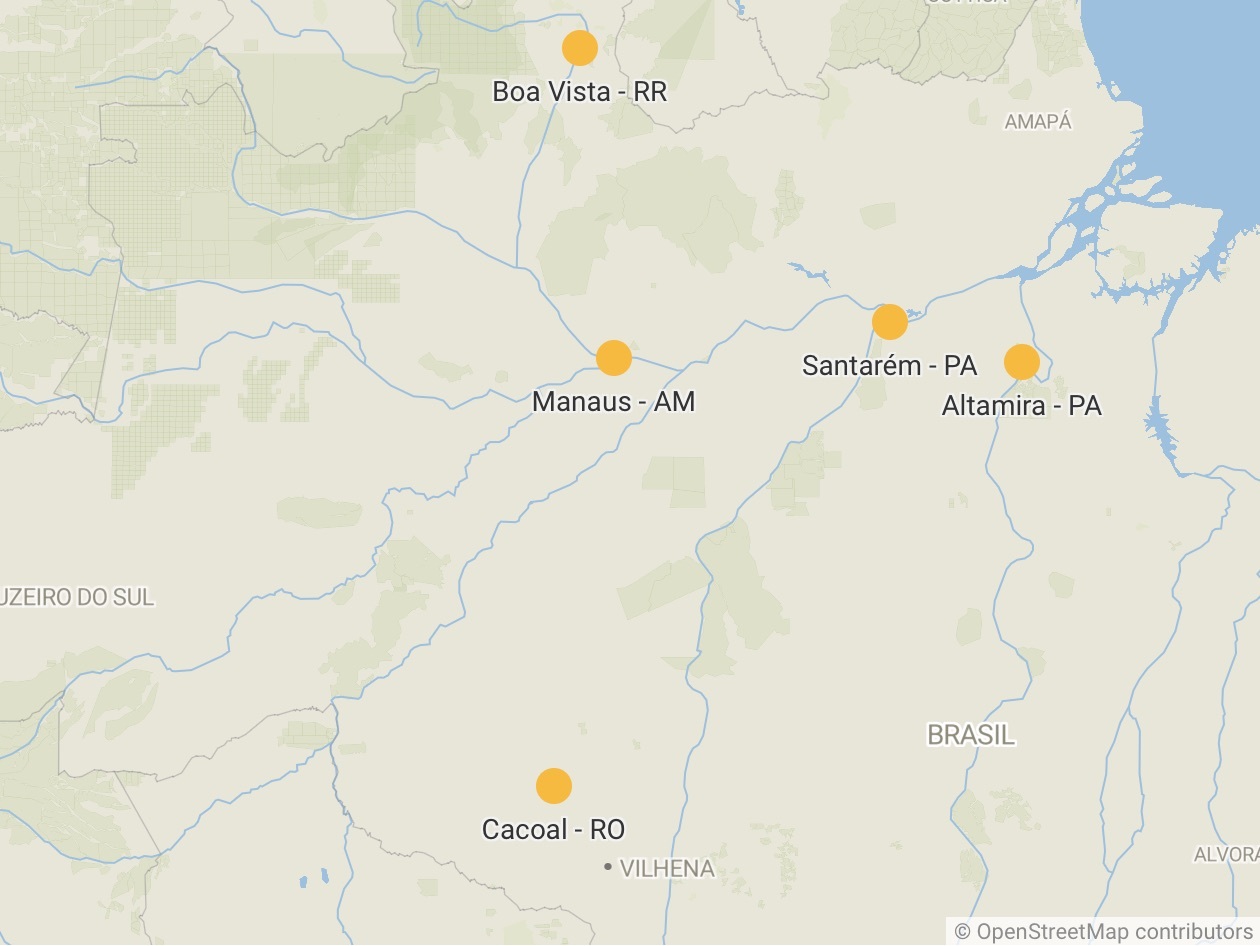

Neglected by government and society at large, indigenous people from the states of Amazonas, Pará, Rondônia and Roraima are organizing against the impacts of yet another pandemic.

The coronavirus pandemic works like a magnifying glass on the denial of indigenous peoples’ identity and on the State and society’s neglect of them for over 500 years.

Historians point out that before the initial invasion of colonizers, 8 to 40 million indigenous people—speaking a plethora of languages and representing the most varied of cultures—lived in Brazil. Since then, their territories have been constantly attacked, and indigenous people have been forced to fight on a daily basis, year after year, for their survival, either against illegal mining, deforestation, government neglect or, now, against the Covid-19 virus.

Vanda Witoto, a nursing technician and resident of Parque das Tribos, an indigenous neighborhood in Manaus, capital of the state of Amazonas, says that their communities have always been neglected. “We’ve been fighting for our survival for 520 years, and we’ve done nothing different during this pandemic. We have already faced other types of viruses. And we live a worse pandemic, which is the daily denial of our identity. This denial invalidates us; it takes away our lives.”

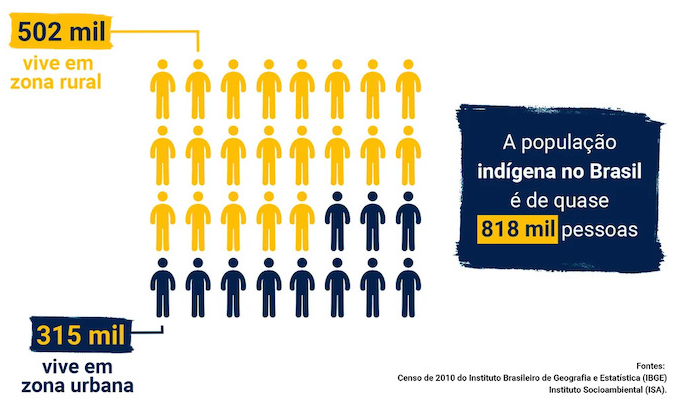

Currently, the indigenous population in Brazil is of almost 818,000 people, 502,000 of whom live in rural areas and 315,000 in urban areas. They are divided into 256 ethnic groups and speak over 160 languages, according to the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA) and the last census carried out in 2010 by the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE). The data, although outdated, show how representative the country’s indigenous population is—and it could be even larger if it did not face a government and society that constantly disrespects, devalues and violates its rights.

The indigenous population can be seen even more clearly when we look at the Northern region, where most of the country’s indigenous people are concentrated. The Brazilian North is known worldwide for the Amazon and for its biodiversity, which has been under attack by miners and loggers profiting from illegal extractivism and deforestation year after year. In this humid and hot region, where communities live on the banks of large rivers, indigenous people, quilombolas (descendants of enslaved Africans who remain on their ancestral lands, formally recognized as quilombos), and, recently, refugees from Haiti and Venezuela come together to make up the place’s diversity.

São Gabriel da Cachoeira, a municipality located 850 km from Manaus, and which borders Colombia and Venezuela, is the Brazilian city with the largest absolute indigenous population (29,000). However, the municipality of Uiramutã, in Roraima, partly on Raposa Serra do Sol indigenous land, has the highest percentage of self-declared indigenous people in its population (88.1%).

The Arrival of Coronavirus in the North

The first case of coronavirus contamination among the indigenous of Brazil was confirmed on March 25, 2020. A young woman of the Kokama people, a resident of the Amazonian municipality of Santo Antônio do Içá, was infected by a doctor from São Paulo working for the Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health (Sesai). Currently, we have already surpassed 242 indigenous deaths by the virus in the state of Amazonas, the largest number in the country. After that, Mato Grosso and Roraima occupy the third and fourth position with 157 and 108 cases, respectively.*

Currently, we have already surpassed 242 indigenous deaths by the virus in the state of Amazonas, the largest number in the country.

Manaus was the epicenter of the Covid-19 pandemic in Brazil and, during the peak of the disease between April and May 2020, the local public health system—which was already precarious—collapsed due to the high number of patients, in addition to the lack of equipment and health professionals. The city was holding about 100 burials per day, leaving more than two million Manaus residents in mourning, along with the families who had to accompany burials through video calls.

Contamination by the virus also affected Claúdia Baré, a resident and leader of Parque das Tribos. The neighborhood, located in Manaus, the most populous city in the North, is one of the territories fighting for and sustaining indigenous culture. Coming from 35 ethnic groups, and speaking 14 different languages, approximately 500 families live there, close to the chaos of the metropolis.

Baré says she had flu symptoms, a fever, and soon after, lost her sense of smell and taste. She and her family, who also had symptoms, were advised by a doctor to try and isolate themselves. “I was unable to breathe properly for five days, and had very strong chest pains. It was a horrible experience. I got better with time and did three tests which were all positive. I still have a few symptoms, but I feel much better,” she explains.

Like other residents of the neighborhood, Baré has no access to Basic Health Units (UBS) or hospitals nearby, so they all relied on the help of Vanda Witoto. The nursing technician started a campaign on social media to collect food for her community, but with the virus advancing and affecting more local indigenous people, she decided to take further measures. “My mother is a seamstress and I bought non-woven fabric (TNT) to try to do something, as we didn’t have the money to buy face masks. I am one of the few people here with formal employment, so I could afford to buy material. My mother sewed the masks and we handed out two to each home, and to those who were already showing symptoms.”

Witoto also said that she produced videos with hygiene guidelines and with explanations on how residents should wear face masks for their protection. Deeply moved and with a trembling voice, she said that social isolation in the neighborhood is impossible because the houses normally have a single room. She points out how these factors lead to an increase in cases in the area.

The technician, who had been monitoring the indigenous people in the community, says that between March and April about 40 residents had mild symptoms of coronavirus. By the end of the second month, however, the more serious signs of the disease began to appear, and she came across several residents with breathing difficulties. “When I saw my first relative have breathing difficulties, I went crazy. The oxygen level in her bloodstream was extremely low and the doctor who was giving me online support advised me to get her to a hospital immediately.” When calling the Mobile Emergency Service (Samu), Witoto had to deal with the institution’s resistance and refusal to send an ambulance to the location.

“The moment I identified the patient, myself, and our community as indigenous, the attendant simply told me that I should contact Sesai (Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health). I explained that because we are outside of our territory, Sesai does not recognize us and will not serve us. I said, ‘I need you to send an ambulance to meet my relative who is about to suffer respiratory arrest.’ Only then did she ask me for our address. I informed her that, as we are far from the city, the only reference is the Vivenda Verde Road and the Balneário do Maia, at which point she told me that she couldn’t release a vehicle on this information,” said Witoto.

The situation reported by Witoto is the result of neglect and lack of recognition of indigenous people living in urban areas. In addition to the difficulty in accessing health care, there is a discrepancy in the number of confirmed coronavirus cases between Sesai and indigenous organizations. Robson Santos Silva, Secretary of Indigenous Health, told the Chamber of Deputies website that this is because Sesai only works with indigenous people living in villages, because those who live in cities can be assisted by the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS).

Disgusted with the situation, and against the wishes of her father and husband, Witoto put on her cloth coat, worn by her as a lab coat, grabbed a disposable face mask and gloves, and took the indigenous woman to the hospital herself. “The State denied us service and neglected us. I faced the fear of becoming infected and took my relative to the hospital. She was hospitalized, thank God she is now fine.”

Unlike the residents of Parque das Tribos, the Xipaya people live in a rural context—although this did not make chieftess Edna Xipaya any less concerned about the new coronavirus pandemic. Altamira, considered the largest municipality in Brazil, is also the closest city to the Xipayas, but they still have to make a ten-day trip to reach it during the dry season, between September and January.

Unlike the residents of Parque das Tribos, the Xipaya people live in a rural context—although this did not make chieftess Edna Xipaya any less concerned about the new coronavirus pandemic. Altamira, considered the largest municipality in Brazil, is also the closest city to the Xipayas, but they still have to make a ten-day trip to reach it during the dry season, between September and January.

Despite this, Edna declared the total isolation of the villages, and blocked the entrance and exit to them, only allowing Special Indigenous Health District (Dsei) professionals in.

Cultural festivities were also interrupted for more than four months. “We put up a sign asking that nobody enter. Although we know that our risk of contamination is lower, we cut off all cultural activities, dances, and festivities within the villages, and so far we’ve had no infections.”

The Internet as a Tool for Survival

With more than 22 years of existence and struggle, Pará’s Tapajós and Arapiuns Indigenous Council (CITA), a non-profit organization, was created to bring public policies to the more than 8,000 indigenous people who make up the Council and live in the municipalities of Belterra, Santarém and Aveiro. These municipalities make up a region known as Baixo Tapajós, a meeting point between the Tapajós, Arapiuns and Amazonas rivers. The organization includes 13 ethnic groups, 70 villages, and 19 territories that are not demarcated, but are geographically recognized by each group.

Edney Arapium, one of the Council’s coordinators, explains that many villages in the region, especially those closest to Alter do Chão, work in tourism or local farming and have been financially affected by the pandemic and social isolation. Concerned with the spread of the virus, and in order to avoid that villagers get contaminated by going to the cities, CITA created an online crowdfunding campaign to raise funds and buy basic foodstuffs, in addition to cleaning and hygiene kits that were donated to indigenous people living in the area.

The coordinator states that the action was critical in preventing the coronavirus from spreading further through the villages. According to him, the villagers live a vulnerable health situation, as there is no healthcare clinic nearby, and in cases of indigenous people with more severe symptoms, care would be hampered by distance. “The crowdfunding campaign was crucial, and we have made three donations so far. We publicized the action and worked hard on cleaning foodstuffs and hygiene kits, which has definitely lowered the contamination rate,” said Arapium.

Rondônia, a state with an estimated population of 1.7 million, has 35 confirmed deaths of indigenous people.* Furthermore, ten indigenous ethnic groups have already been affected by the virus, including the Pandareo Zoro and Puruborá, according to data from the National Committee for the Life and Memory of Indigenous Peoples, published by the Emergência Indígena (Indigenous Emergency) website. The Rondônia Indigenous Women Warriors Association (AGIR) used online crowdfunding as a way to address this situation.

In addition to basic foodstuffs and hygiene and cleaning kits, the money raised by the campaign was used to purchase local farming materials and tools, as stated by Maria Leonice Tupari, coordinator of the Association. “This measure is necessary for women and their families to continue their agricultural production. We participated in several public grant-making opportunities and established a few partnerships to raise more funds. There are also women who lived off of handicrafts, and with the pandemic had nowhere to sell their goods. We bought some pieces and are selling them through an online store. In this way, everyone helps each other, which has been essential for our survival.”

Altogether, over 51,000 indigenous people have been infected, leaving 1026 dead and 163 ethnic groups affected in Brazil.* Regarding a lack of effective decision-making on the part of the Bolsonaro administration and state institutions, Tupari says that indigenous struggle and resistance has always existed, especially on the part of women, and that this is not the first time her people have been decimated. “The government is not committed to public health, not only for indigenous people, but for all of society. Our ancestors have already lived through several viral epidemics and were almost wiped out, but now Covid-19 has arrived, and it is our turn to fight against the invisible”, said the coordinator.

Miners Out, Covid Out

In June 2020, a study carried out by the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA) in partnership with the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) and reviewed by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), pointed out that about 40% of the Yanomami living near areas of illegal mining in the Yanomami Indigenous Lands (TY) could become contaminated by the coronavirus. Currently, there are already nine confirmed deaths among the Yanomami, as indicated by the Emergência Indígena website.

With 9.6 million hectares of land and 27,000 indigenous people spread over approximately 331 communities, the Yanomami people, living in the states of Amazonas and Roraima, are the most vulnerable to Covid-19 among the Brazilian Amazon peoples. According to ISA, this is due to the fragile health systems of the two states, and a history of respiratory diseases among the Yanomami.

“[…] The Yanomami have a high rate of illnesses that can aggravate coronavirus infections. According to the Health Information System for Indigenous Peoples (Siasi), in the last ten years (2010 to 2019), the number of deaths related to acute respiratory infections (J00 to J22) increased by 6% in the population between ages 0 and 14, and 300% in the population 50 and older,” as stated in an excerpt from a report carried out by the Institute.

Furthermore, both the ISA report and indigenous organizations indicate illegal mining as the main cause for the spread of the virus among indigenous people. According to them, it is estimated that 20,000 illegal gold prospectors live less than five kilometers from Yanomami Land. As a result, six organizations, including the Yanomami and Ye’kwana Leadership Forum and the Hutukara Yanomami Association (HAY), launched the campaign “Fora garimpo, fora Covid” (Miners Out, Covid Out).

Dario Kopenawa, vice president of Hutukara and son of leader and shaman Davi Kopenawa, one of the main people responsible for the Yanomami land demarcation, says that the objective of the campaign is to pressure government into removing miners from Yanomami Land. This was done by delivering more than 400,000 signatures during the virtual session of the National Congress’s Joint Parliamentary Front in Defense of the Indigenous Peoples, held on December 3, 2020.

“The mining is extensive, and, because of that, there is a lot of deforestation, our rivers are contaminated, and health problems are even greater. We have already held meetings with the authorities and even with Brazil’s vice-president [Hamilton Mourão]. I asked him to remove the miners as soon as possible and he promised he would, but so far has done nothing,” said Dario.

The vice-president of Hutukara says that the government does not have the power to ban or restrain miners, but he expects it to do its part. In the meantime, Dario says that Hutukara and other indigenous associations have been defending the rights of their people and working to prevent the new coronavirus from reaching more community members. “We’ve been explaining what the coronavirus is, and how we can protect ourselves. Since all of this has delayed farm work, we have been trying to help with emergency aid, as well. We asked our communities to avoid going to Boa Vista or other nearby municipalities, to ensure that we set up a health checkpoint. But we did it on our own because we couldn’t get support from any government.”

Indigenous Knowledge

A spoonful of andiroba (crabwood) to treat a sore throat; boldo tea for the liver; and, of course, the traditional garlic tea with lemon for the flu. This is just some of the vast knowledge taught by our grandparents to take care of a flu or even more serious illnesses and which, despite not being scientifically proven by so-called traditional science, continues to be transmitted across generations.

This knowledge is even stronger and present in the roots of indigenous culture. With the State’s absence during the coronavirus pandemic, communities turned to traditional indigenous medicine to try to prevent and treat Covid-19. Cláudia Baré, who was infected at the beginning of the year, says that while she had the virus, her partner made jambu tea with lemon, or garlic and honey tea for her to drink. According to Baré, both combinations are used to treat the flu and to strengthen immunity.

It was no different for chieftess Edna Xipaya. With no cases of coronavirus in her villages, the chieftess says she used teas to remain healthy and prevent contamination. “Here in the Xipaya community, we drink certain teas to cure the flu, and to reduce the risk of making others sick. We have several herbs, barks, and seeds that are harvested from the forest and used in our teas and blessings.”

Edney Arapium, coordinator of CITA, in Pará, explains that teas and blessings are part of indigenous culture, and that these practices are ways of preserving the lessons passed on by the elders. “It is a way of valuing our culture and a teaching that will never die. All children are born knowing, and this is passed on from parent to child.”

“Corona” in Northern Peripheries

Along with indigenous peoples, residents of the outskirts of Manaus and Belém, the two largest capital cities of the Northern region, face the most severe impacts of Covid-19. This reinforces the notion that the populations most vulnerable to the coronavirus are those who have always been seen, socially, as peripheral. Manaus’ Women’s Solidarity Network and Belém’s Telas em Movimento (Moving Screens), both groups registered in the Coronavirus in the Peripheries Map launched by Favela em Pauta and the Marielle Franco Institute, are two of the many organizations in the North developing strategies and actions to fight the pandemic.

The Women’s Solidarity Network was created in March 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, and is part of the city’s Permanent Forum of Women, founded in 2016 and bringing together 18 active collectives. A few days before social isolation was officially decreed, the group was following cases of femicide in Manaus, where they noted that, in one case, the victim’s family was living in precarious conditions. Later, more families were identified in the same circumstances.

Antônia Barroso, one of the Network’s members, explains that the group discussed the families’ circumstances and decided to take action. They wrote and presented to the Prosecutors Office a document demanding effective measures from public authorities. Additionally, they set up a campaign to raise funds and food. “We were concerned with the impact that this was going to have on the lives of families, especially those headed by independent women. We divided up the tasks, publicized the campaign, and managed to donate food, face masks, and cleaning and hygiene products in various parts of the city. We always took all possible health precautions, and continued demanding that state and city government take responsibility,” said Barroso.

In Belém, Telas em Movimento has taken a different approach. An initiative of Negritar Films and Productions, Telas em Movimento promotes democratization in cinema, and stimulates a new dynamics in film creation, perception and distribution in the peripheries and traditional communities of Pará. In addition to distributing basic foodstuffs and cleaning kits, the project, which recently won a grant, noted that children in the periphery had a distinct need.

Telas em Movimento works with and for peripheral neighborhoods, quilombos and some of the islands that make up Belém. Matheus Braga, a member of NaCuia Productions and spokesperson for Telas em Movimento, says that in considering places facing problems with access to basic sanitation and electricity, the project team also questioned, “What will children do during these months of isolation? What will they do for fun?”

The project distributed a teaching kit called “Telas da Esperança” (Screens of Hope), in which children could do activities and draw, in addition to creating stories of superheroes who fought against Covid-19 within their own communities. “We then collected most of these notebooks and set up an exhibition at the Theodoro Braga Gallery, here in Belém. It is a prestigious place in the city and this was the gallery’s first children’s exhibition. We are now holding workshops for twenty black youth who are learning animation,” said Braga.

In a second stage, the youth participating in the workshops are producing an animation based on the children’s drawings. Their film will soon be shown in the outskirts of the city. “We have been operating on several fronts, and this represents a continuation of our work with the children,” concluded Braga.

This is the second article in a five-part series titled “Brazils: Stories of the Periphery in the Pandemic.”

*Data updated from original Portuguese article’s publication date, as per Emergência Indígena’s Covid-19 data dashboard for the indigenous population.