This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

To understand present-day favelas, we must first recognize their origin as urban communities that had their right to decent housing denied by the State and the market. We should start from when favelas started, so as to reflect on what we understand of them today. This is key and will also help us understand the evils of slavery and how this process still, directly, impacts young people in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas. From there, we will try to understand in greater depth what the anti-racist struggle is. And its relationship to the right to the city.

The State’s Role in the Emergence of Rio’s Favelas

In Rio de Janeiro, communities without the right to decent housing go back to colonial times. In 1808, the flight of the Portuguese royal family to Rio de Janeiro and the transfer of the Court to Brazil put a lot of pressure on housing in the city. Collective housing, such as tenements, emerged as a solution. Attention was drawn to them when some were expelled from those homes to give space to the escorts of the Portuguese Crown. During this great wave of displacements, people discovered they were being evicted when they saw, scribbled on their doors, the letters “PR,” initials for “Prince Regent.”

In Rio de Janeiro, communities without the right to decent housing go back to colonial times. In 1808, the flight of the Portuguese royal family to Rio de Janeiro and the transfer of the Court to Brazil put a lot of pressure on housing in the city. Collective housing, such as tenements, emerged as a solution. Attention was drawn to them when some were expelled from those homes to give space to the escorts of the Portuguese Crown. During this great wave of displacements, people discovered they were being evicted when they saw, scribbled on their doors, the letters “PR,” initials for “Prince Regent.”

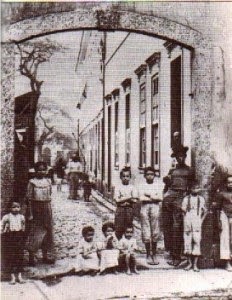

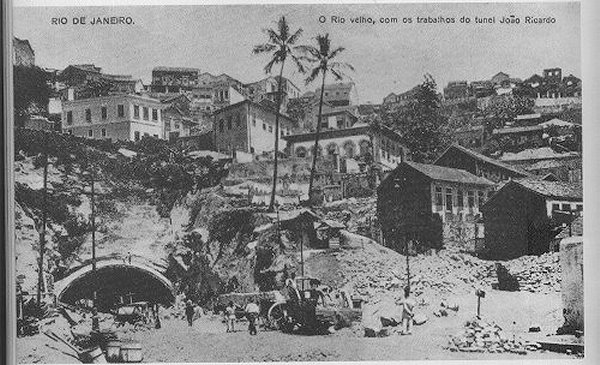

Rio’s largest tenement was called Cabeça de Porco, or “Pig’s Head,” and was located where the João Ricardo Tunnel is today, between the Central do Brasil train station and Gamboa, a neighborhood in the Port Region. At that time, tenements began to be seen as dangerous and insalubrious places, to be demolished and removed. It’s the same old story: if something comes from poor and Afro-Brazilian communities, it is negatively seen.

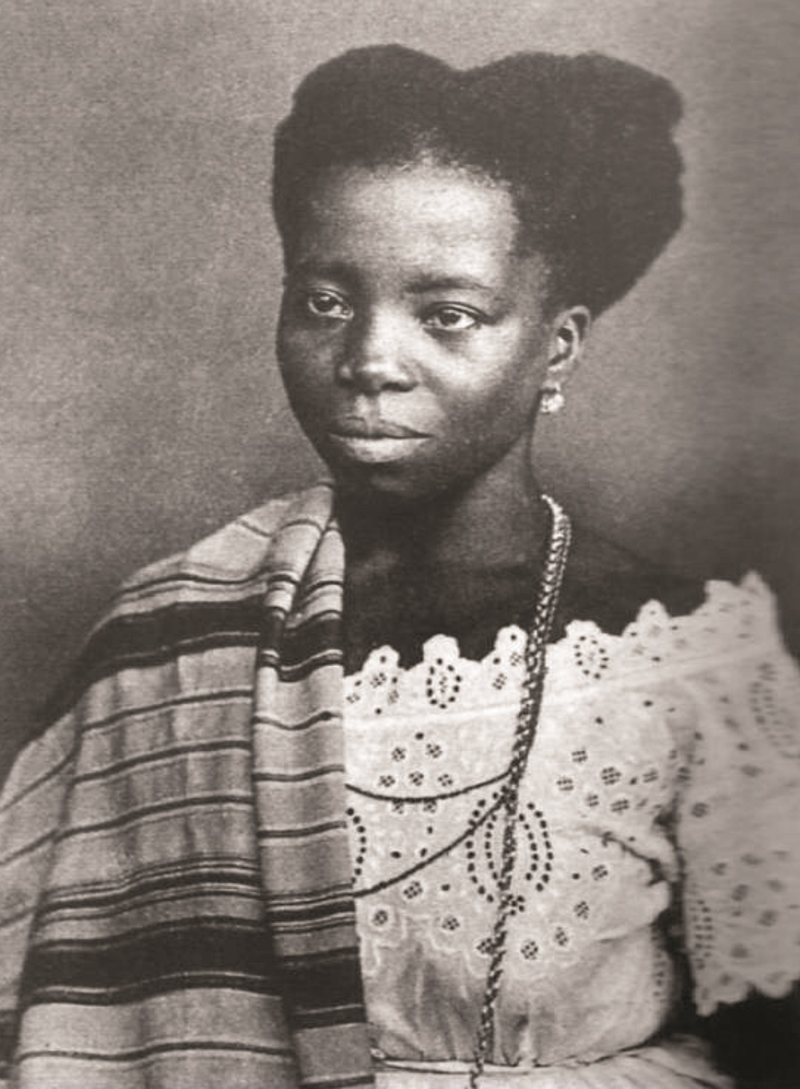

Some time later, in the second half of the 19th century, abolitionist movements began to gain traction. Some enslaved people bought their emancipation, while others fled and set up quilombos, communities of runaway slaves. According to reports, the first quilombos were set up a few years before the abolition of slavery, in what was then the periphery of Rio.

This was the case of Quilombo da Penha, currently the Vila Cruzeiro favela in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone. It was also the case of the Quilombo da Serra dos Pretos Forros, which divides Jacarepaguá from Grande Méier, between the North and West Zones of Rio. And there was the Quilombo do Leblon and Quilombo Sacopã, located in today’s South Zone. The range of communities and locations give us a sense of how quilombos were founded across the city in search of freedom and housing.

In 1888, when Brazil’s Golden Law was finally passed, abolishing slavery, enslaved blacks earned the right to freedom. There was no formal policy for the integration of the formerly enslaved into the salaried labor market, however. With no reparations, no insertion into society, and no access to the labor market, they had no guarantee of survival.

As a result, there was a mass migration of unemployed Afro-Brazilians to the nation’s cities. Since they did not have the means to buy or rent legally, they moved into overcrowded tenements, or into former quilombos, or they squatted and built homes on forested and therefore unoccupied hillsides. By this point, we can already see that the right to freedom was not, and still isn’t, synonymous with citizenship or the guarantee of basic rights.

At the start of the 20th century, Rio de Janeiro underwent a significant urban renewal project led by then-Mayor Pereira Passos. Encouraged by President Rodrigues Alves, their intention was to conceal the capital’s air of backwardness and traces of the legacy of slavery. Their aim was to make the city modern, building squares, widening streets, and investing in basic sanitation, inspired by the Paris of Haussmann. The idea was to turn Rio de Janeiro into a Paris of the tropics. With this, tenements considered insalubrious spreaders of disease, and of high risk to public health, were torn down, and their residents displaced.

After this urban renewal, the authorities’ policy towards those recently freed from slavery continued to be one of abandonment. Nothing was done to help insert them into the labor market. Nothing was done as far as housing was concerned. For those who were evicted from tenements, the alternative available was to occupy nearby hillsides, such as Providência and various other hills surrounding Centro, Rio’s downtown. From then on, the words favela and morro (hill) became practically synonymous in the city.

Today, even favelas located in flat areas may be called morros. The social imagination regarding tenements, favelas, and morros carries a markedly negative moral load about these territories, their residents and habits. They are the “non-place” from different eras. They are what is left for the black, for the poor, and for the migrant populations to live.

Resistances to the Criminalization of the Favela and of Black and Favela Culture

The criminalization of poverty and of blackness mark the establishment of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas and their stigmatization. It is not just the favela that is seen as something pejorative, but also everything that is born from it—all culture, forms of resistance, everything that identifies or represents it.

One of the most persecuted and stigmatized products of black favela culture was born in the second half of the 19th century in the bay region of the northeastern state of Bahia. That was where samba, which would turn into one of the most important cultural influences of Rio’s favelas on the world, was born. A distinctly African musical style, samba became popular in Rio de Janeiro in the 20th century, after freed Afro-Brazilians migrated from Bahia to the nation’s then-capital.

A cultural legacy of the African diaspora, samba circles were branded illegal. They were banned and considered “immoral,” synonymous with vagrancy. The racism against Afro-Brazilian culture and religions was part of a colonial project, and continues today, exemplified through criminalization of carioca funk music.

Nevertheless, neither the State nor the white morality of the elite have kept samba from flourishing. It was common for samba circles to take place in terreiros and other locations considered sacred to the Afro-Brazilian religions of Candomblé and Umbanda. They also happened in the homes of the priestesses of both religions, or mães de santo. These places of worship were fundamental for the survival and development of samba, whose cultural identity maintains undeniable traces of religion. Some even call samba the music of the Orixá, as Candomblé deities are known. The percussion, drums, and rattles do not lie: samba comes from the terreiros of samba schools, terreiros named after Candomblé sites of worship. Samba also represented leisure and support networks, a way of welcoming new migrants to the community.

The trajectory of samba, from this early history to the place it now holds as one of Brazil’s most celebrated cultural contributions, was arduous and slow. What was initially seen in a bad light began to gain a positive image in the 1920s. This was when samba stopped being persecuted and became the main source of carnival music, taking the place of prior rhythms such as marchinhas, maxixe, and polka. After the repercussion of the first samba ever to be recorded and released in 1917, “Pelo Telefone,” samba would never again cease to be the music of carnival.

Decades later, another black music genre closely identified with favelas and peripheries took over Rio de Janeiro: carioca funk. In the 1970s, during the military dictatorship—a period of strong repression and censorship against cultural manifestations considered subversive—funk music was introduced from the United States to Brazil. Black cultural production, whether through funk, R&B, or the black music movement, sparked fear among elites and in the regime. They were fearful of the spread of messages exalting racial freedom and struggles against the system. To the military regime, favela residents and Afro-Brazilians were potential revolutionaries.

However, with the passing of time, Brazilian funk distanced itself from its North American roots and built its own identity. Carioca funk lyrics express the complex reality of daily life in favelas. Not reflecting the lived experience or moral patterns of the elite, carioca funk depicts instead the life, desires, and routines of those who are chronically “othered.” To Brazil’s elite, favelas and everything born there can only be understood from a logic of violence or cultural poverty—a narrative perpetuated by mainstream media.

Nevertheless, favela and peripheral residents—whose realities script funk songs—reaffirm the representativeness of the genre. Forty-year-old Teresa Cristina, of the favelas of Complexo do Lins, describes: “Funk is so important, it’s so culturally rich! It pulls so many people out of marginality. It gives us opportunities through dance, through music. You can become an MC, a dancer. In my opinion funk balls are positive. People have fun there… I grew up going to them.”

To many favela residents, funk balls are places of entertainment, of culture, and of possibilities. During the parties, young people have direct contact with artistic figures and clear opportunities for development. Funk is an instrument with the power to transform lives. It engenders personal and financial mobility through music and dance for favela youth.

Funk, like samba, is hugely important to favela culture. Both forms of musical expression can be life-changing. Both influence how people dress, speak, and act. For today’s youth, the funkeiro style is the embodiment of transformation, of social mobility. To their elders, samba brings all the artfulness and flexibility needed to deal with life’s trials. Both represent favela life expressed in words, favela experiences turned to music.

Race, Resistance, and Territory

From their origins to today, favelas can’t be spoken of without covering the relationship between race, resistance, and territory. Favelas were born in different moments, for different reasons. They were born of the fight against slavery. They were born of the lack of reparations. They were born of the denial of post-abolition rights. And they were born of the deliberate denial of public housing policies, but one element of the generalized neglect by the State towards its poorest.

From their origins to today, favelas can’t be spoken of without covering the relationship between race, resistance, and territory. Favelas were born in different moments, for different reasons. They were born of the fight against slavery. They were born of the lack of reparations. They were born of the denial of post-abolition rights. And they were born of the deliberate denial of public housing policies, but one element of the generalized neglect by the State towards its poorest.

The struggles of favelas are far from over. Favela resistance is a survival strategy. You have to resist in order to deal with the arduous daily routine imposed on these territories. Meanwhile, to elites, everything in and from the favela is inferior and must be criminalized, even its victories and forms of expression. Just like it once was with samba, black cultural expressions from favelas are usually persecuted until the middle class adopts them. Then they triumph. Sometimes, after conquering the white middle class, favela culture can even become a tool for social control by the State, as was the case with samba during the 1950s.

Favela resistance goes well beyond culture. It is the daily and collective struggle of favela residents against racism and for life. And it is a struggle that must engage all of society. Racism here is firmly rooted and explicit, yet paradoxically veiled, for black and favela lives. In Brazil, racism is the motor of a black genocide, while classism is the fuel. A chronic symptom of racism, police violence in favelas killed, in the first six months of 2019 alone, 885 people, 711 of whom were black or brown. In other words, close to 80% of those killed by the police in 2019 were black, while 56% of the Brazilian population is black. It is of vital importance to be aware that being anti-racist is the key for a better life in favelas, since being a black favela resident in Rio de Janeiro is synonymous with fighting and resisting, but not always of surviving.

About the author: Paulo Gabriel dos Santos is an undergraduate student in social sciences at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ). Having taught children with special needs at a public school near the favela of São Carlos, he has recently begun working as a community communicator with the aim of making favela knowledge and information reach as many people as possible.

About the artist: Born and raised in Complexo do Alemão, David Amen is co-founder and communication producer of the Roots in Movement Institute, a journalist, graffiti artist, and illustrator.

This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.